Terror, Erebus, and the Search for the Northwest Passage

Europeans have long sought a route through the Arctic Ocean, linking the Atlantic with the Pacific. Despite many failures, the lure of the Northwest Passage has enjoyed remarkable longevity.

The discovery in 2016 of the Royal Navy’s HMS Terror near the west coast of King William Island in the Canadian Arctic was an exciting moment for historians. The position of the ship and its archaeology promised to fill gaps in our knowledge of what occurred during one of the most significant mysteries of sea-going exploration: the fate of the last expedition of Sir John Franklin. It was an opportune moment to consider why Franklin and his men were in the Arctic in the mid-19th century. To answer this question, we should look not just at the circumstances that drove the crews of HMS Erebus and Terror to the Arctic, but at the broader political and economic situations which have drawn people north from the British Isles since at least the 15th century. More importantly, we should also pay attention to how this exploration impacted on the communities of the Arctic as a result of their interactions with men from the south. The Arctic may still be understood as an uninhabited, empty space, but in reality, the places encountered by explorers were populated and embedded with rich cultural meaning and indigenous history.

European enthusiasm for Arctic exploration has, in post-medieval history, been driven by the pressures of national and continental politics. By the 15th century, kingdoms and city states became powerful through their ability to control, or at least affect, the trade in Middle Eastern and Asian goods. The desire to compete in this trade drove Portugal to seek a sea route to Asia via Africa, while the Spanish search for a route across the Atlantic initiated their encounters with, and exploitation of, the Americas. By 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas and resulting Papal Bull had asserted these nations’ control over trade routes and profits originating from the sea routes they had charted. For other European nations, this created a significant problem: the scales of regional political power shifted as the resources available to the Spanish and Portuguese crowns dramatically increased. If other kingdoms, such as England, wanted to keep up, they would need to find their own routes to the riches of ‘Cathaya’ (China) and the rest of Asia.

Despite the need to keep pace with continental politics, English attempts to locate alternative trade routes were initially faltering. It was clear from the start, however, that the Arctic would be their focus. During the reign of Henry VII, John and Sebastian Cabot were involved in attempts to find northern routes to China and Japan but the reign of Henry VIII saw the lobbying of traders such as Robert Thorne largely ignored, due to the king’s other preoccupations. The reign of Elizabeth Iwas a different matter altogether.

Faced with a desperate struggle in which her reign, religious beliefs and kingdom were threatened by the actions of external powers, Elizabeth turned to the seas and, more specifically, to a generation of adventurers and privateers. Men such as Martin Frobisher were instructed to harass foreign shipping and to search for trade opportunities that would benefit England. When we think of polar explorers today they are, as we will see later, of a different mould from men like Frobisher. We think of men such as Cook, Franklin and Scott as members of a British naval culture that valued rigour, scientific enquiry, organisation and various other seemingly ‘straight-laced’ traits. Men like Frobisher were happy to live on the edge, aggressively taking opportunities where they could be found and often making up rules as they went along. They were the sort of adventurers who were prepared, in today’s terms, to undertake a mission to Mars in nothing more than an Apollo landing module.

The maps left in published accounts of Frobisher’s expeditions illustrate why he and his like were prepared to set out for the north in the small, comparatively delicate vessels of their time. There was a strongly felt belief, which would persist across the centuries, that sea water of sufficient depths and vigour could not freeze and, as a result, there must be open sea channels via the North Pole and routes such as the Northwest Passage. This theory meant that Frobisher left port in England confident he could find a passage to Asia and, hopefully, encounter other sources of trade and resources on the way. In the fifth century BC, in his Histories, Herodotus mythologised the riches of the north, especially amber and skins, and an idea persisted that there were kingdoms in the high Arctic where these materials and even gold could be found and traded.

What Frobisher encountered on his expeditions, conducted between 1576 and 1578, was great difficulty navigating treacherous waters and ice, something that looked like gold and groups of indigenous Inuit. The Inuit encountered were not the great kingdom he hoped for, however, and their presence also meant these lands were peopled, which led to conflict.

Frobisher would eventually undertake three expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage, in spite of his difficulty in finding an open trade route, because of the presence of what he thought was gold. His search for and attempted extraction of this material brought him into significant contact with Inuit in areas which now form part of Greenland and northern Canada. Frobisher, however, was an adventurer and a privateer, not a man keen to understand and work with local cultures, so his actions often led to conflict. One such encounter, probably a battle at a place named ‘Bloody Point’, is depicted in a manuscript that once belonged to Sir Hans Sloane, founder of the British Museum, and also contains illustrations of Inuit captives brought back to England.

Frobisher’s attempts to find the Northwest Passage and extract valuable goods ended in failure, not least because the vast quantities of gold he extracted turned out to be useless iron pyrite, which still decorates parts of Dartford to this day. His failure did not diminish English interest in a passage, however, it established a pattern. Over succeeding centuries English and, later, British explorers would head across the Atlantic in search of trade routes, gold and an elusive political advantage in an increasingly global world.

Interest in finding a Northwest Passage continued during the 17th and 18th centuries, with moments of feverish activity. Sir Francis Drake and Henry Hudson scoured the coasts of North America for entrances to the Passage, while back in Europe, politicians and cartographers, such as parliamentarian Sir Arthur Dobbs and speculative cartographer Philippe Buache, would argue for its existence and shaped cartographic imaginations in order to illustrate their ideas.

This was set against a background of continued competition in Europe. The power of Spain and Portugal waned during this period and British power grew, but increased competition from France and the Netherlands, among others, meant the global stage was more crowded than ever. It was during this period of feverish political competition that Lieutenant, later Captain, James Cook commanded three voyages of exploration, between 1768 and 1779. Cook’s first two expeditions charted the east coast of Australia, confirmed New Zealand as an island and cast final doubts on the existence of a Great Southern Continent, something which the explorer had always suspected. Departing on his third expedition, in 1776, Cook carried secret instructions, which detailed his intended endeavour to search for an entrance to the Northwest Passage from the Pacific Ocean.

In contrast to his disbelief in the Great Southern Continent, it seems Cook believed there could be a navigable passage, if not a trade route, via the Arctic and was determined to find it. His search for the Passage was conducted as the last part of his expedition, after his Pacific exploration was complete, the idea being that Cook would navigate the Passage and be able to return to London via the North Atlantic. Fully provisioned, he set out with his two ships, Resolution and Discovery, to chart the west coast of North America in the hope of finding a navigable channel. After encountering the landmass now known as Vancouver Island, Cook continued north but was disappointed to find the coast extending not only further north than he anticipated but also starting to bear west.

A long, dangerous and dispiriting search followed, the perils and frustration of which are captured in John Webber’s prints of the expedition. Cook’s failure to find the Passage also led to his death. Turning back meant he had to attempt to restock his ship at Hawaii. It was this return journey which instigated a misguided attempt to capture and ransom the Hawaiian monarch Kalani’ōpu‘u-a-Kaiamamao and ended in a fatal affray on a beach in Kealakekua Bay. By this point the search for the Northwest Passage had claimed many lives but the expedition and death of Captain Cook marked both a beginning and an end. His failure to find a navigable route cooled British interest in Arctic exploration for many years, with few serious attempts made until after the Napoleonic Wars. However, Cook’s expedition was also one of the first in which the British Admiralty took a direct interest in the search for a passage. This was to be significant in the century to come and the search would be very different from this point.

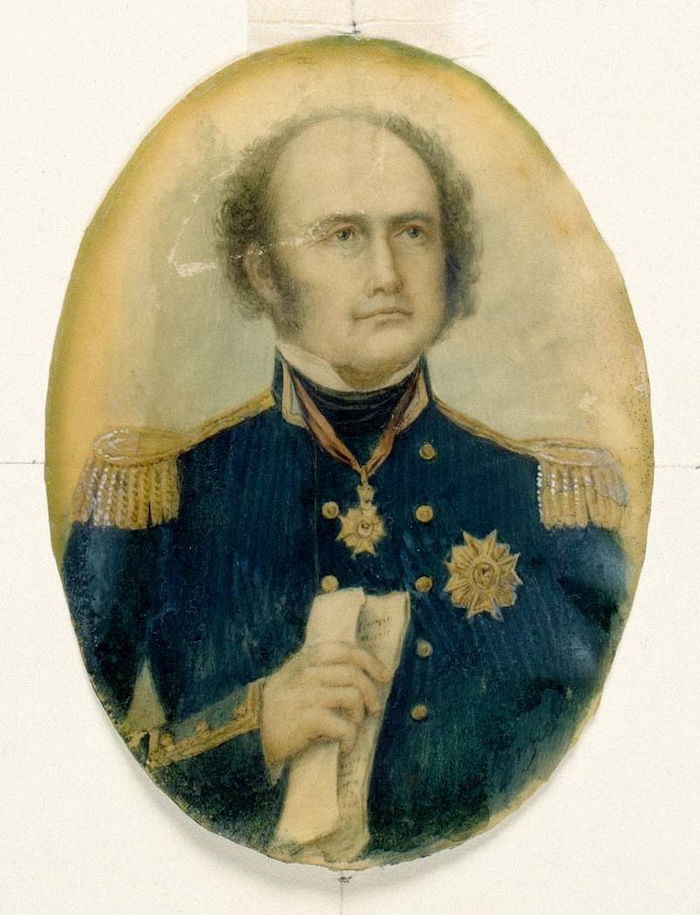

After the Napoleonic Wars, Britain was in a position of naval and political dominance around the globe. The end of the wars also left Britain with a surplus of naval officers and materiel and few projects in which to use them. Sir John Barrow, Second Secretary to the Admiralty, saw an opportunity to restart the search for the Northwest Passage. Barrow’s endeavour would be recognised today as a display of ‘soft power’, where national prowess is displayed through the achievement of scientific and technical feats, and he too recognised the significance of a British naval expedition discovering the Northwest Passage. Barrow lobbied for expeditions to be sponsored and from 1818 various searches were sent out by sea and land as a result of his actions. The men who commanded these expeditions are well known – Sir John Ross, Sir James Clark Ross, Sir William Edward Parry and many others – but few are remembered as widely as Sir John Franklin.

Franklin was a decorated veteran of the Napoleonic Wars and took part in Barrow’s expeditions, first in junior roles, but found fame for his leadership of two overland journeys that attempted to chart the Northwest Passage from the northern coast of North America. These expeditions, conducted in 1819-22 and 1825-27, were made famous by the John Murray publications that recounted the tribulations faced by Franklin and those who accompanied him. While the horror of the expeditions – which included extreme weather, erratic planning, loss of life and suspected cannibalism – was documented in the books, Franklin became a celebrity for one particular passage and became known as ‘The Man Who Ate His Boots’.

These expeditions, along with many others arranged by Sir John Barrow, Secretary of the Admiralty by this time, ended in only marginal gains in the exploration of the Northwest Passage. So many expeditions were sent out and failed that it was now clear, should anyone admit it, that this was not a viable trade route, but attempts continued as pride and prestige became an increasing focus. The continued failure to find a passage mixed with the personal failures of Sir John Franklin, who also had a disastrous tenure as Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) between 1836 and 1843, are perhaps the reason why Barrow and Franklin ended up collaborating on a final throw of the dice, with a major sea-based attempt to find the Passage setting sail in 1845.

Franklin now commanded HMS Erebus and Terror, two bomb ships, armed with mortars, which had seen military service around the world. Both ships had sailed to Antarctica under the command of Captain James Clark Ross and, during its military service, HMS Terror was involved in the siege of Fort McHenry in 1814, firing some of the artillery which inspired the US anthem, ‘The Star Spangled Banner’. No expense was spared in preparing the ships for their new polar expedition, and the crew left with all modern conveniences at their disposal: anti-scorbutic foods, monogrammed cutlery, musical instruments, canned foods and more were taken to care for the men and officers on board. Leaving London to much fanfare before resupplying at the Orkney Islands – well used to Hudson’s Bay Company ships and polar explorers passing through – the ships were seen by the crew of the whaler Prince of Wales on July 26th, 1845 in Lancaster Sound, the eastern entrance to the Northwest Passage. After this, both Erebus and Terror disappeared.

The disappearance started one of the biggest searches for missing persons ever undertaken. Ships from Britain and the United States, containing crews comprised of men from across the globe, scoured all of what would become the Northwest Passage. A passage was traversed for the first time during the 1850-54 expedition of Captain Robert McClure, although he lost his ship and completed the route on foot. However, few clues to the fate of Franklin and his crew were turned up. There were grisly discoveries, such as bodies strewn across the Canadian Arctic, suggesting that something had gone wrong and men had tried to walk away from danger, and some facts uncovered but ultimately nothing to reveal the fate of the ships. Furthermore, no one knew if any members of the expedition were still alive.

A number of Inuit groups who lived around King William Island did in fact know what had happened and they would eventually pass their information to Dr John Rae. Rae was not just one of the most formidable explorers of his age but one of the most impressive European explorers in history and yet he is largely forgotten. Qualifying as a doctor in Edinburgh and coming into the employ of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Rae developed a reputation for his abilities as an explorer, which would bring him to the attention of Franklin’s wife. After her husband’s disappearance, Lady Franklin dedicated herself to marshalling the search for her husband, mounting a formidable press campaign and maintaining pressure on the Admiralty to search for the expedition. So concerted were her efforts that the residence she took up near the Admiralty offices became known to those she dealt with as ‘The Battery’.

Hearing of Dr Rae’s abilities, Lady Franklin encouraged him to undertake an overland journey of exploration, which would also search for evidence of her husband’s fate. It is worth noting that Rae’s approach was the antithesis of Franklin’s naval expeditions: travelling light, with just a few key tools to aid his expedition, such as Peter Haklett’s ‘Boat Cloak’, Rae had learnt to live off the land by observing First Nations and Inuit travelling practices. He had also learnt, unlike many Europeans, to listen to the advice and knowledge of indigenous people. This practice would bring him crucial information about the Franklin expedition, as well as some very public arguments back in Britain.

Returning from his 1853-54 expedition to complete the survey of the Arctic coast of North America, sponsored by the Hudson’s Bay Company, Rae encountered a party of Inuit who were keen to trade. The goods for trade clearly belonged to the Franklin expedition, as they included inscribed silverware and Franklin’s own Order of the Bath medal; they also came with information as to the expedition’s fate. The Inuit Rae met told him a group of Kabloona (white men) had been encountered four winters before struggling south and the following summer their bodies had been found, showing signs of cannibalism.

Rae returned to London with this information, reporting it to the Admiralty as the story broke in The Times. This news was not, however, what society at large – and certainly not what Lady Franklin – wished to hear. The news of cannibalism appalled Victorian society: it was an act many believed men serving in the Royal Navy to be incapable of and Lady Franklin began a vigorous campaign to salvage her husband’s reputation. As a result, Rae came under attack from various commentators, encouraged by Lady Franklin to lend their opinions to her cause, including Charles Dickens. The great English novelist was an enthusiast for dramatic stories of Arctic exploration, as shown by his participation in performances of his play The Frozen Deep, and he published attacks on Rae’s information in his publication Household Words.

While being careful to praise Rae’s abilities as an explorer, Dickens attacked his willingness to believe the accounts of Inuit he encountered on the journey. The author believed indigenous testimony to be worthless, stating: ‘The word of a savage is not to be taken for it; firstly because he is a liar; secondly, because he is a boaster.’ While Rae’s information was correct, its veracity was successfully undermined in the eyes of many. Sadly, following Dickens’s example, many have continued to articulate such ideas, casting aspersions on the veracity of indigenous oral testimony to this day.

It is worth noting, then, that both the Erebus and the Terror were located in areas around King William Island where Inuit oral history has long suggested searchers should look. As Rae’s information has been backed up by various archaeological expeditions, which proved that cannibalism did occur among the struggling, starving remnants of Franklin’s crew, these recent finds suggest Inuit testimony has been significant in other areas, too. Testimonies heard by various Franklin searchers, such as Charles Francis Hall, attested to the importance of the site. Captain Francis Leopold McClintock, who gave Terror Bay its name, also heard Inuit accounts, which noted significant events around the expedition’s end happened in the west of King William Island.

Over half a century after Rae returned with his news about Franklin’s expedition, the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen led the first expedition to sail through the Northwest Passage between 1903 and 1906. Like Rae, Amundsen used Inuit techniques to successfully prepare, undertake and supply his expedition, using a small boat, equipping his men in skins and furs and attempting to live off the land as much as possible. Amundsen, too, found resistance to his methods from proponents of more ‘civilised’ forms of exploration, but both Rae and Amundsen mark important points in our attempts to understand and appropriately interpret the knowledge, culture and techniques of indigenous cultures.

Today small ships regularly sail the Northwest Passage, while plans are being developed to send cruise liners and, inevitably, trade ships through a warming Arctic. The long search for this route shows that current interests in the Arctic are nothing new; politics have long driven us there in search of trade routes and resources. This history should also caution us not to treat the Arctic as a blank, open space, but one filled with indigenous knowledge and meaning, which we should make every effort to respect.

Philip Hatfield is Lead Curator, Digital Maps Collections at the British Library. He is the author of Lines in the Ice: Exploring the Roof of the World (British Library Publishing, 2016).