Swahili on the Road

How did Swahili become an East African lingua franca? It was not by accident.

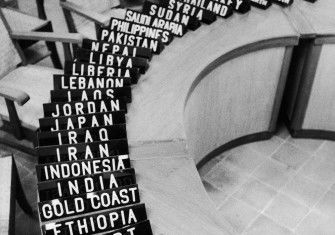

In March 1960 Julius Nyerere – then leader of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) – sat down with former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt on her roundtable discussion programme Prospects of Mankind. The topic was ‘Africa: A Revolution in Haste’. Although he found himself in a sympathetic circle of interlocutors, Nyerere was asked to defend the ‘readiness’ of African peoples for independence. Good-humoured but resolute, he replied: ‘If you come into my house and steal my jacket, don’t then ask me whether I am ready for my jacket. The jacket was mine, you had no right at all to take it from me … I may not look as smart in it as you look in it, but it’s mine.’ With a simple analogy, Nyerere swept aside the argument that decolonisation was happening too quickly. And though this defence was delivered in composed and commanding English – the language of his degrees at Makerere College in Uganda and Edinburgh University – the language that Nyerere championed at home was Swahili.