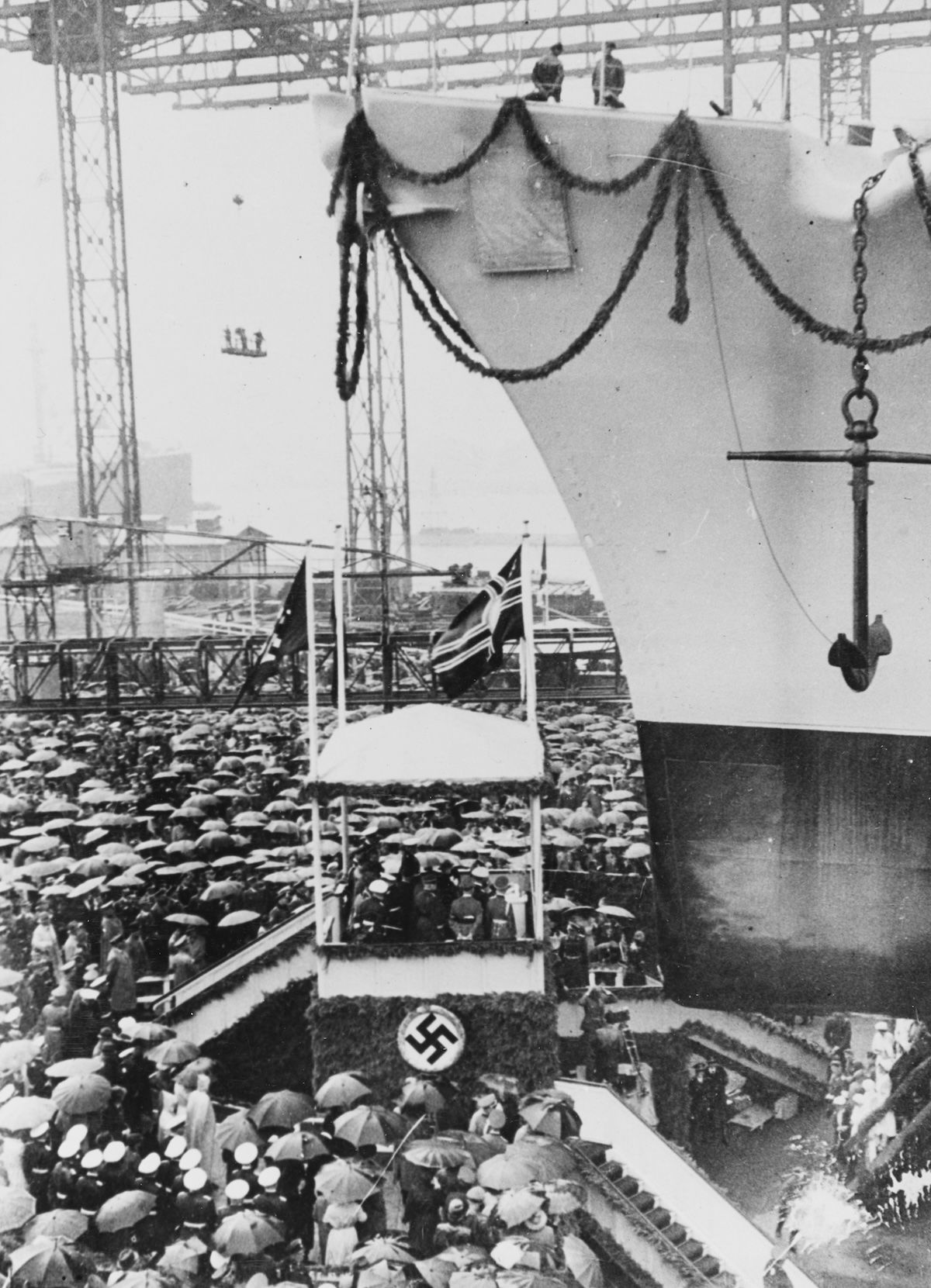

The Lützow and the Sinking of the Nazi-Soviet Pact

Eventually sunk during the defence of Leningrad, the unfinished German cruiser Lützow is a fitting symbol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

On the last day of May 1940 a peculiar sight appeared in the approaches to Leningrad. A German heavy cruiser was being towed into a shipyard on the western edge of the city. There was no bunting, no military band and little ceremony. No mention was made of the arrival in the Soviet press; instead, the newspapers Izvestia and Leningradskaya Pravda reported the Anglo-French collapse at the other end of the Continent in studiedly neutral tones. Consequently, the huge grey monster attracted little attention as it was nudged and cajoled into place by puffing black tugs. Nonetheless, its arrival was an event of profound significance.