A Mine of Statues

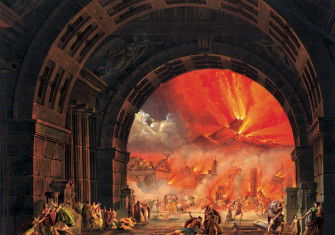

Charles Seltman presents the discovery and patronage of Herculaneum as a classical drama.

Archaeology is the discovery, recording, study and interpretation of material evidence surviving from the past of mankind. It therefore partakes both of scholarship and of science and is the natural union of two “Arts” which never should have been imagined as separate or in opposition, since it were true to say that scholarship should be science and science, scholarship.

Yet archaeology was begotten of Greed and conceived in Pride of Possession; it was bom in a royal Court; sycophants were its nurses and hangers-on its servitors. But among the strange group of human beings who set all this on foot, and whose antics and intrigues can still provide some pleasing entertainment, there was one good man, one scholar-scientist— a Swiss engineer. Though he has been almost forgotten his memory should be for a blessing. Where others had hunted for antiquities like hogs digging for truffles, he measured, planned, recorded, kept a diary of the work in progress. For that reason this obscure man, Carl Weber, must be honoured as the first real archaeologist.

It all happened against the romantic background of the eighteenth-century Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and on the shores of the Bay of Naples. During the War of the Spanish Succession an Austrian army, profiting by victorious actions performed elsewhere by Marlborough and by Prince Eugene, advanced through Italy annexing various Spanish possessions. In July, 1707, just as an Austrian viceroy was being installed in Naples, there came to that city a certain Emanuel Maurice de Lorraine Prince d’Elboeuf, who, being a distant cousin of Prince Eugene himself, held a command in the Austrian army and was now posted to the city which attracted him. He threw himself into the social life of the Neapolitan aristocracy, amongst whom he was known as the Duca di Belbofi, which was the best they could do with his name; he was betrothed to a certain Princess Salsa in 1710, and spent the summer of that year in the villa of a Conte di Santi Buono at Portici by the sea immediately below the western slopes of Vesuvius.

No one at that date had any ideas about the situation of the ancient towns of Herculaneum and Pompeii which had been overwhelmed in the colossal eruption of the volcano in a.d. 79. That was something which the learned read about in books, as you read about the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrha; but it had not occurred to anyone to seek to relate the happenings to a site. Now, in 1710, a farmer near Portici decided to deepen his well in order to increase his water-supply, and, digging to a depth of some sixty feet through several layers of solidified mud, he chanced suddenly upon marble fragments and bits of columns. When this came to the ears of d’Elboeuf he purchased the site and hired workmen to extend the dig in the hope of finding statuary, being presently rewarded with the discovery deep underground of some great building—not yet identifiable— and with numerous statues, the best being three fine white, marble, draped female figures. Though he built himself a villa at Portici where he might house most of his finds, he decided to make a present of these three draped figures to his cousin Prince Eugene for his palace in Vienna, since d’Elboeuf had need of the princely goodwill. Therefore, the statues were first smuggled into Rome to be repaired by some statue-faker. This was essential; for, while Prince Eugene, like many another nobleman of the time, was an ardent collector of “the antique”, it would have been an insult to present him with incomplete figures. So one marble lady was supplied with a false head, the others with some fingers and toes. From Rome the now completed statues were smuggled to Ancona, thence by sea to Trieste and finally to Vienna where they were vastly appreciated. Meanwhile, d’Elboeuf married his Neapolitan bride in 1713 and settled in his new villa at Portici to gratify his lust for more marbles; but since duty frequently called him away, the excavations slowly petered out, he sold his villa, and no one knew as yet that there had been discovered a part of ancient Herculaneum. When Prince Eugene died in 1736, a bachelor and intestate, his heiress, a niece, sold the three marble women to Augustus III, Elector of Saxony, and King of Poland, and they were transferred to Dresden where they presumably still adorn the Saxon Collection.

The d’Elboeuf episode was, as things turned, out, but a prelude to greater discoveries which were to come soon after the Austrians were expelled from Naples in 1734, when the Spanish-Bourbon Line recovered possession of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. With the Spanish army that took Naples came Prince Charles Bourbon, eldest son of a Frenchman, King Philip V of Spain, and of an Italian Princess Farnese, now Queen Elizabeth of Spain. The young Prince was in the following year formally appointed King with the style of “Charles III, King of the Two Sicilies and Jerusalem.” Under him and at his instigation the great discoveries were made and, in retrospect, it seems rather as though they took place upon a stage set for Light Opera or Comedy— not inappropriately, for it was King Charles III who founded in 1737 the world-famous Teatro San Carlo in Naples. And here, lest the story seem too complicated, it will be best to summarize the Characters roughly in the order of their appearance.

King Charles Ill: very intelligent and well-informed, spoke several languages and had studied history and the sciences; a lover of music and fine art, especially sculpture, because, from his mother’s side, the Royal Collection at Naples obtained much from the Farnese Collections including some of the worst monstrosities of ancient sculpture. He had a passion for hunting and for sea-fishing and loved to work with and among the ordinary longshore fishermen. The faults of his character were a collector’s greedy acquisitiveness which was matched to a secretiveness about his possessions arising from his fear that others might be the first to publish facts about them. Such was his nature until in 1759 he became King of Spain. How he had by that time developed will be that age, his only blemish being a huge beak of a nose well shown in the portrait of him by Pademi.

Queen Maria Amalia Christina: married to Charles in 1738, a daughter of Augustus III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, the same prince who had purchased the three marble women discovered by d’Elboeuf at Portici. Since her father was a passionate collector of painting and sculpture she had grown up art-conscious and therefore with tastes exactly like Charles’, including a tendency to secretiveness about antique possessions. In contrast to him she was difficult of access, domineering, irascible and violent, and even ladies of the nobility must kneel in her presence. A competent Queen but distinctly unpleasant.

Tanucci: a good Prime Minister, a keen antiquarian, the young King’s first Counsellor, ultimately restored to favour after having been superseded for a while by...

Fogliani: a bad Prime Minister, scheming and venal, hated by the Queen who saw through him.

De Alcubierre: a Spaniard—and the only one in the comedy—by profession a land-surveyor, but having come to Naples with the King, was created “Colonel i.c. R.E.’s Naples”; perhaps a good land-surveyor, but without knowledge of antiquity or of mining; fortunately aware of his own limitations; probably a lazy man.

Camillo Paderni: a painter, a Roman, employed principally as Keeper of the Royal Museum in the Villa at Portici, but also to repair, retouch and preserve fresco-paintings discovered in excavations. Painted the King (see illustration), a lazy sycophant of a man who broke up any frescoes which seemed to him insufficiently complete.

Guiseppe Canart: a sculptor, a citizen of Rome whence he was imported by the King in 1739; almost a genius, certainly a most gifted worker in marble and bronze, he produced no original creation of any moment, but took the easy way of faking antiques; unfortunately not lazy— like Pademi—and therefore a greater destroyer of the piece.

Carl Weber: the hero; a Swiss engineer whose skill and efficiency were matched by his industry and common sense; he went in for the unheard-of practice of drawing ground-plans and keeping a diary of the excavation; was in charge at Herculaneum from 1750 onwards. It is difficult to find out more about Weber who suddenly appears, like Captain Bluntschli in Arms and the Man, a professional amongst amateurs and shams.

Monsignor Ottavio Bayardi: from Parma, a cousin of Fogliani, who put him forward for the lucrative appointment of scholar and expert to the excavations; he had built up for himself a purely fictitious reputation for learning, but was a screwy, muddleheaded, conceited scribbler; his excuse for playing the role of a parasite was perhaps the fact that he was small, sickly and hard up. By 1755 he at last published under pressure a bare catalogue of finds, but the fall of his cousin Fogliani in that year entailed Bayardi’s dismissal, which was most fortunate.

Father Antonio Piaggi, S.J.: One of the Officials in the Vatican Library, appointed in 1754 by the King to unroll the papyrus rolls discovered at Herculaneum; he worked exceedingly slowly and his success was very small; spiteful, a gossip and a back-biter who enjoyed blackening most of his comrades.

Such were the ten people most nearly connected with the excavations at Herculaneum.

Young King Charles had not been long at Naples before he decided to go fishing and found his way to Portici. The place, the beach and probably the local fishermen pleased him, and, looking round for a small property he found he could get the villa which had been built by d’Elboeuf some twenty-five years before. When he went to view the house he was astonished and enchanted by some of the ancient marbles which had been left behind and instantly bought the place, determining, once he was established, to continue the excavations. In this he was presently much encouraged by his young Queen who shared his acquisitive zeal for antiquities. The first result of pursuing the sixty-foot-deep work on the same site was to produce more statues, parts of two splendid bronze horses, and—at last—an inscription proving that the building being dug was the Theatre of Herculaneum. And so it was only in 1738 that it became a certain fact—most pleasing to the King and most stirring for the learned world of Europe— that Herculaneum had been found. The site of Pompeii remained unidentified for another twenty-five years.

More statues from the Theatre, bronze and marble, from a square outside, then private houses found with frescoes which were cut from the walls and taken aloft to the bright light where they began to fade. But the King and Queen were both happy with their “mine” for works of art; and for a while their staff was switched to ruins near Civita Vecchia in 1748, and here Carl Weber, the Swiss, took charge. Two years later the work went back to Herculaneum, where another attempted well-shaft north-west of the “Theatre shaft” revealed the first signs of an impressive and wealthy private residence: and it was especially on this most difficult and elaborate “dig” that the genius of Weber showed itself. The work was a kind of underground mining in which, once the requisite level of a building was reached, you made trial passages till you came to the corner of a main wall, then “squared up” on this comer, followed the rectangular building and examined its contents: if you were Weber you made a sketch-plan with careful measurements and listed your finds; if you were not you pulled out any object you might find and then filled in again.

The impressive residence excavated by Weber proved to be the finest villa of the late Republican and early Imperial ages that has ever been discovered even to this day, and almost all the best bronzes now in the Naples Museum came from this one place:—the resting Hermes, the two wrestling boys, two satyrs, six girls in Doric dress, many bronze busts—two Greek originals among them— were found, almost in perfect preservation. Then many marbles also turned up, and presently there was made in the same villa the most sensational of all finds, a library of over six hundred manuscript papyrus rolls. Here was work for the whole of the King’s staff and especially for the all too industrious Canart. He had begun his wicked ways when the Theatre was identified ten years before by making a perfect false head for the equestrian marble statue of a certain Balbus, and by breaking up four incomplete horses and building their bits together to make one complete animal. The Charioteer, and any other bronzes which seemed to Canart too troublesome to cook up, he simply melted down, making from them numerous bronze statues of Saints as well as medallions of King Charles III and his Queen. This doubtless gratified greatly the Saints in Paradise and their Majesties on Earth.

It was the discovery of the superb villa which set on foot the fullest activity at Herculaneum. King Charles in his raptures even forgot his beloved sea-fishing. De Alcubierre worried, Pademi painted and engraved, the Queen arranged, Canart faked, Bayardi dithered, Piaggi, he of the malicious tongue, procrastinated; only Weber acted, measured, explored, recorded. In 1735 the King founded the “Herculaneum Academy” which gradually took in hand a sumptuous publication of the finds, and, as the volumes slowly appeared and became more slowly known outside the Kingdom of Naples, the effect upon the learned, as well as upon the polite, world of these superb antiquities depicted in the volumes was immense. Already in 1756 a certain Dr. Robert Watson was making reports to the Royal Society about the finds and supporting the identification of a manuscript as the work of the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus. By 1773 an English edition, not only abbreviated but, much to King Charles Ill’s indignation, pirated, by two Cambridge scholars appeared. It contained a summary of Bayardi’s wordy catalogue, and engravings of numerous fresco-paintings, some copied by a Cambridge draughtsman named Lambom from Pademi’s engravings. They are not good, but are interesting as showing how the precision-loving eighteenth-century eye desired to see good first-century Greek impressionistic painting. But the Cambridge volume by Martyn and Lettice, two Fellows of Sidney Sussex College, was very popular, being subscribed for by members of the nobility and gentry, and of the Bench of Bishops, and by Heads of Houses, Fellows and College Libraries.

For Charles III an end came to happiness in 1759. His half-brother, Ferdinand VI of Spain, died, and Charles was called upon to wear the Spanish Crown, leaving the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to his eight-year-old, backward son under the regency of the excellent Tanucci. The King must leave the Royal Villa at Portici for the Escorial. No more of the songs of Neapolitan fisherman who were his real friends, no more nets and lines, no smell of tarry boats and of the salt sunny sea, but only the long halls and chilled galleries of an inland palace heavy with memories of piety, cruelty and pain. The King went, for that was his duty; but he took nothing with him from all his wonderful collection. Even an ancient gold ring which he had found among a hoard of gold coins on one of his countless visits to Civita Vecchia and which he had worn ever after on his hand and shown it with pride— even this he took off and left in the State Collection. Perhaps it would have hurt too much to look at it in Madrid. His Majesty had begun to collect in a spirit of greed, but time had changed and mellowed him, for there was much good in him. The spirit of the ancient world began to affect him strongly, and even to incline him to a movement away from his own medievalist and royalist traditions. Martin Hume, the historian, pointed out that he went to Spain with,

“ministers and friends belonging to the new ‘philosophical’ French School, who looked upon religion as a relic of the dark ages, and exalted the secular power of the monarchy in order to oppose the priest”.

Looking back upon his happy Neapolitan days he would reflect that a little roguery within the framework of a civilized society was preferable to gangsterism in a cloak-and-dagger culture. The Madrileños, with their long black cloaks, wide hats, daggers and oily side-whiskers, seemed far from picturesque to King Charles, who had come from a Court which he had made one of the most civilized in all Europe.

He died, aged seventy-three, in December, 1788, and Hume has written of him as “the only good, great and patriotic King that providence had vouchsafed to Spain in modern times. Enlightened, generous, and just”. The enlightenment and humanism of the King were due neither to any innate virtues of a Bourbon, nor to the traditions of his royal and princely forbears, but to contact with the freedom of the ancient world renascent through Herculaneum.

An archaeologist of today is able to assess the value and interest of Weber’s work in the great villa beside Herculaneum only because the Swiss engineer left behind a rough plan with measurements, records of where works of art and manuscripts were found, and a diary , of the excavation. Weber’s discoveries, indeed, were much more important than he knew. The statues, of course, suffered restoration at the hands of Canart in accordance with the prevailing fashion. His worst misdeed was to scrape the patina off all bronzes leaving them the dull dark brown colour which they still display. He had a dislike of the hollow eye-socket and therefore—except where ancient enamelled eyes had been preserved—he inserted false, dead-fishy, bronze eye-balls. Many of his smaller repairs have escaped notice to the present day; but one of his larger and more misleading forgeries needs to be exposed. In the first century B.C., and probably later, there was a vogue among wealthy Roman collectors for statues of kanephoroi—that is of Greek girl basket-bearers—carrying baskets made probably of gilt bronze wire, such figures having been frequently dedicated by the girls’ parents in sanctuaries like the Athenian Acropolis. The owner of the Herculaneum Villa possessed six such life-size statues which were bronze copies of well-known Greek originals; but one of them, on being excavated by Weber was found to be without head, neck, throat and right arm; and, if Canart was only too eager to use up other bronze fragments in order to supply what was missing, he was merely conforming to the wishes of the Royal Collectors. Since all the other five fifth-century bronze girls were markedly individual, he decided to make his fake different too, and copied her face and the general effect of her coiffure from a life-size third-century female bust (nowadays known as “Sappho”) which Weber had likewise discovered in the same Villa. A mere stylistic difference of two centuries was to Canart immaterial; yet having got into his head the, notion that these bronzes represented “dancers,” he made for the girl a forged arm and hand, so placed as to suggest that she was executing a leisurely pirouette. Thus, by means of a forgery long-ignored, all the girls came to be called danzatrici, and not a few modern producers of Greek dramas have allowed their ideas of choreographic effects to be influenced by a misconception due to a forgery by Canart —how appropriate his name!

And all of this is by the way; because in our day it has been possible to establish beyond all doubt that Weber’s Villa and its statues— scraped and part-faked by Canart—were the property of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, Consul in 58 B.C., and father-in-law of Julius Caesar. The library, consisting of hundreds of papyri belonged to his “house-philosopher,” Philodemus, who was leader of all the Epicureans in his day and who lived in the Villa and taught in its spacious gardens because Calpurnius Piso favoured that philosophy. Piso himself, whom Cicero attacked with unbalanced fury, was one of those men of genius and tireless energy which the Republic produced at the very period in its history when it was destined to merge into the Roman Empire. At his death the Villa passed to his son, a man of different calibre, though of equal eminence.

Yet it is due to Weber’s natural precision and carefulness that this knowledge of an important corner of the ancient world is ours, and if ever a history of field-archaeology is written, his name must be mentioned even before those of the famous nineteenth-century pioneers like Sir Henry Layard, Mariette, Schliemann, Petrie, Dorpfeld and Sir Arthur Evans. Not only did Weber begin almost a century before Layard started, but he had a task more difficult than the one that faced Schliemann, when in 1870 he began to cut into the hill of Hissarlik and gradually discovered stratum on stratum, proving the existence of numerous past cities of Troy. It is often supposed that in A.D. 79 the town of Herculaneum was overwhelmed by molten lava from Vesuvius. Had that been so every bronze statue would have become a formless metal mass, every marble a lump of burnt lime, and every manuscript a little heap of ashes. What happened was that streams of boiling mud flowed down the mountain, and this horrid substance seeped into every nook and cranny. But it was in its way an excellent preservative, since as it cooled it set fairly hard. For centuries between a.d. 79 and the huge erruption of 1631, Vesuvius deposited a series of mud-layers on Herculaneum, and it was into these that farmers dug in search of water, and it was through the lowest of these layers that Weber drove his big subterranean galleries to find the ground-plan of the great Villa built by Lucius Calpumius Piso. Within the present century the Italian authorities have excavated several other sections of Greek Herculaneum and, at great cost, have removed layer after layer of the solidified mud which overlies the town. Even had he desired it King Charles III of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies could not have afforded what was possible to Benito Mussolini. Today, however, one may observe, side by side, the modern excavations and one of the wide entrances into Weber’s galleries and may perceive, over the adit, stratified layers of solid mud—each one the token of a volcanic upheaval—mud which increases the fertility of the Vesuvian earth, while it embarrasses the excavator.

The Regent Tannucci’s confidence in Weber was such that, when in 1763 certain ruins near Civita Vecchia were identified by an inscription at the city of Pompeii, the Regent put him in sole charge because he had proposed a new and methodical plan of excavation. Diggers were no longer to plunge haphazard into the ground, but the scheme was to move steadily forward by streets and blocks; and houses, instead of being filled in after looting ended, were to be left open to view. But that year was one of misfortunes for Naples which suffered from a famine; and some disease, hurtful to the undernourished, struck Weber down. He had worked for about fifteen years at the excavations and was presumably still fairly young when he died. The fruits of his skill and industry have endured.