‘Make the Foreigner Pay’: When Britain Tried Tariffs

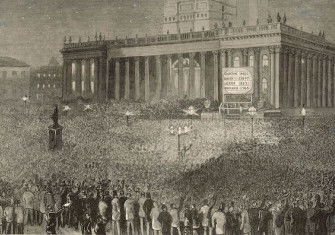

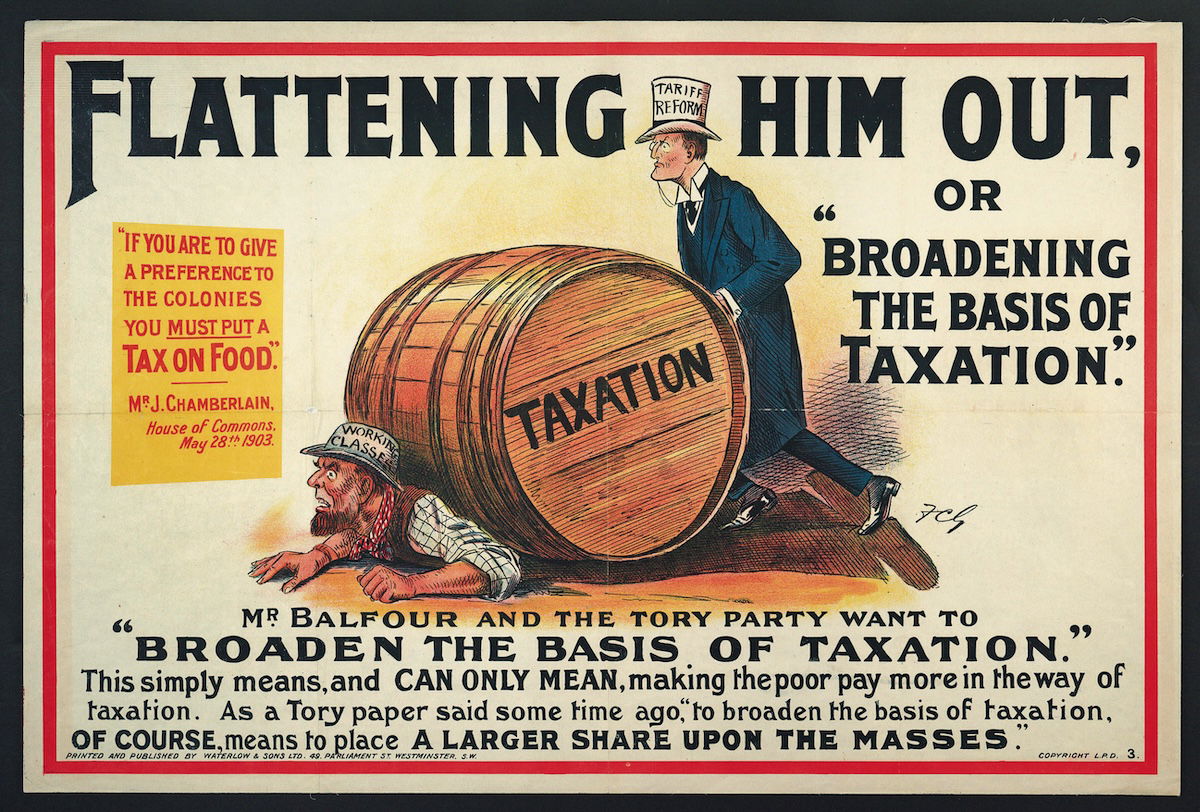

In 1903 a group of politicians tried to sell tariffs as a panacea to all of Britain’s problems. Would the public buy it?

In the early 20th century few political issues inspired such passion and vitriol in the United Kingdom as whether to impose tariffs on imported goods. An apparently esoteric issue of high-level fiscal and trade policy, politicians and journalists wreathed tariff reform in signifiers relating to national pride and imperialism. The conservative Morning Post, one of the most persistent pro-tariff newspapers, declared in 1914 that the policy should ‘appeal to the national and Imperial spirit of Englishmen’. Tariff proponents derided their opponents as ‘little Englanders’, not capable of ‘thinking imperially’. Free trade advocates mocked tariff reformers for ignoring economic realities and accused them of planning to impoverish Britain’s working classes.