What was the Industrial Revolution?

Over the 18th and 19th centuries Britain’s economy, technology, and society were transformed by the so-called Industrial Revolution. Why?

‘Industrial organisation defines people’s lives’

Judy Z. Stephenson is Professor of the Economic History of the Built Environment at the Bartlett, UCL

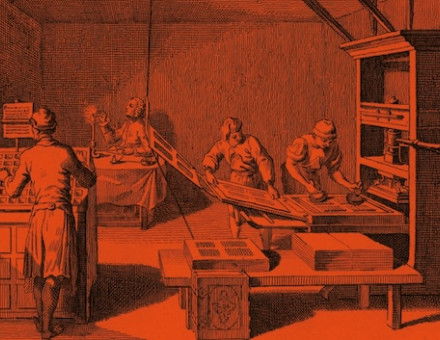

The Industrial Revolution was a profound crisis and upheaval in industrial organisation, or the way people work. This is a far more useful description than any which emphasise the shift away from agrarian production, or the growth of capitalism, or a ‘wave of gadgets’, or the mass exploitation of a new energy source. The economies of northwestern Europe had advanced beyond the agrarian well before the late 18th century, T.S. Ashton’s ‘gadgets’ started during the late Renaissance (with lots of capital), and coal was already used intensively, too. It is only with the organisation of the movement and production of large volumes of goods using new technology in big workplaces over regular hours that the real revolution began.