Arab Invasion of Africa: The First Islamic Empire

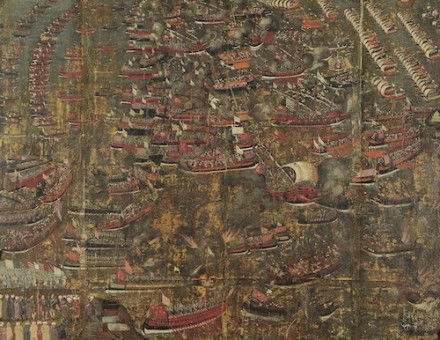

During the seventh century the Arabs invaded North Africa three times, bringing not just Islam but a language and customs that were alien to the Berber tribes of the Sahara.

When Muhammad, the Prophet of Islam, died in 632 the new religion had already gathered a number of impressive victories on the battlefield. The armies of Islam quickly and easily conquered the Arabian peninsula before moving on to take the homelands of their various neighbours. Marching out of Arabia in 639 they entered non-Arab Egypt; 43 years later they reached the shores of the Atlantic; and in 711 they invaded Spain. In just 70 years they had subdued the whole of North Africa, instituting a new order. This conquest, from the Nile to the Atlantic, was more complete than anything achieved by previous invaders and the changes it wrought proved permanent.