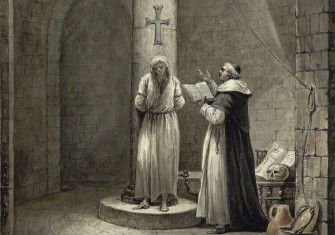

The Jesuits Were the Inquisition’s Secret Weapon

Intending to convert souls rather than punish them, the Jesuits were vital collaborators in the early modern Roman Inquisition.

In August 1556 a 24-year-old student from the Kingdom of Naples was boiled alive in a pot of oil, pitch and turpentine in Rome’s Piazza Navona. The student’s name was Pomponio Algieri. His crime was an error of belief. Algieri had publicly and persistently claimed that the Catholic Church taught lies, that the pope had no authority and that people should be free to join churches other than the Church of Rome. To our ears, Algieri’s ideas are relatively uncontroversial. But to the cardinals of the Roman Inquisition they could not have been more dangerous.