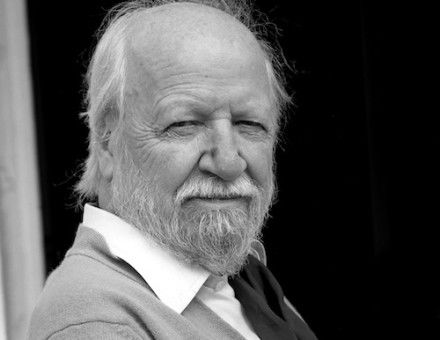

Edmond Halley: Astronomer and Explorer

Edmond Halley was far more than a man who watched comets. His adventures aboard HMS Paramour represent one of the earliest voyages of purely scientific discovery.

On August 2nd, 1700, a cluster of English fishing boats settled off Toad Cove, Newfoundland. Their calm routine shattered as an ill-favoured craft bore down on the flotilla; pirates were active along the coast, and few honest sailors welcomed the sight of a strange, dishevelled vessel. Captain Humphrey Bryant's trawler had already fought off one attack, and his crew had no stomach for polite introductions. Five rounds of red-hot shot roared from their swivel guns and sliced the brigand's rigging. The ship abruptly anchored as an agitated figure jigged about the poop deck, treating Bryant to a torrent of abuse impressive even by North Atlantic standards. It was maritime history's least likely Black- beard – Edmond Halley, FRS.