Eurodämmerung

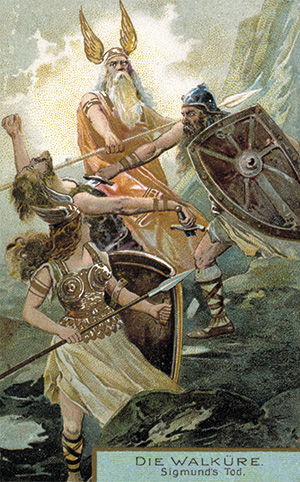

As the Eurozone countries wrestle with the fate of the single currency, Mark Ronan discovers parallels in Wagner’s Ring cycle.

Wagner’s epic music-drama, which he began in the revolutionary year of 1848, starts with the Niebelung Alberich forging a ring of power from gold he stole from the Rhinemaidens. In the meantime the gods construct their palace of Valhalla. They don’t have the money to pay for it, so they trick Alberich out of his treasure in order to pay giants to build it. The giants demand the ring in payment: one kills the other, turns into a dragon and guards his treasure.

Wagner’s epic music-drama, which he began in the revolutionary year of 1848, starts with the Niebelung Alberich forging a ring of power from gold he stole from the Rhinemaidens. In the meantime the gods construct their palace of Valhalla. They don’t have the money to pay for it, so they trick Alberich out of his treasure in order to pay giants to build it. The giants demand the ring in payment: one kills the other, turns into a dragon and guards his treasure.