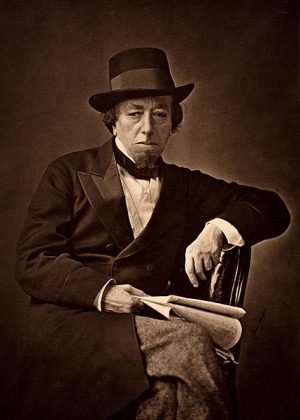

Disraeli and the Conservative Leadership

Richard Cavendish recreates the scene of the famous Victorian Tory leader's accession, on February 22nd 1849.

As the year 1849 opened, Benjamin Disraeli was 44 years old and Conservative MP for Buckinghamshire. He had been in Parliament since 1837 and after a famously disastrous maiden speech he had made his emphatic mark in the House of Commons, driven his own leader, Sir Robert Peel, out of office and engulfed the Conservative Party in a damaging split between the supporters of Peel and the majority who as adamantly opposed him. The schism would keep the Conservatives out of office for most of a quarter of a century, but meanwhile Lord Stanley, ‘the Rupert of debate’, future Earl of Derby, was the recognized leader of the majority Protectionist or anti-Peelite Tories. He sat in the House of Lords, with Lord George Bentinck as leader of the group's 230 or so MPs in the Commons, where Disraeli was his principal lieutenant.

George Bentinck was a younger son of the eccentric Duke of Portland (whose laudable, if rare, habit was to communicate with his family only in writing), a formidable sporting aristocrat who owned one of the finest racing stables in England and whose greatest ambition was to win the Derby. He resigned the Commons leadership at the end of 1847 after he and Disraeli had failed to carry their followers with them in voting to remove the civil disabilities of the Jews. Disraeli, who was Jewish himself and proud of it, clearly could not succeed Bentinck in these circumstances. He had reproached recalcitrant MPs in his speech for being influenced by ‘the darkest superstitions of the darkest ages that ever existed in this country’. The Duke of Rutland's son and heir, the inadequate Lord Granby ‘his high Castilian emptiness,’ Disraeli privately called him), briefly took charge, but his heart was not in it and for most of 1848 the Commons Conservatives had no leader. Many hoped Bentinck would return and there was shock and dismay when he was carried off by a sudden heart attack at the age of 46 in September when out walking near Welbeck Abbey.

Disraeli was the obvious successor. Outsiders thought him the only man of real talent the Conservatives had, but he was regarded with profound suspicion by Lord Stanley, the two party whips and most of the Commons' rank and file. Indeed, a less likely and more outre figure to lead the Tories it would be hard to imagine. He was Jewish, foreign-looking, flamboyant, bitingly witty, cynical and overdressed. His finances and past relationships with women were suspect. He was too clever and pleased with himself by half, and he wrote novels.

Lord Stanley, recoiling, tried to find a leader in J.C. Herries, a former Chancellor of the Exchequer, but Herries, who was 67, declined in January 1849 and Stanley was reduced to organizing a triumvirate of Herries, Granby and Disraeli to share the leadership. There was no question who was the dominating figure in this trio, which Lord Aberdeen compared to ‘Sieyes, Roger Ducos and Napoleon Bonaparte’. The editor of the Morning Herald described the arrangement as a device ‘to place the leader of the Conservative Party like a sandwich between two pieces of bread (very stale bread – Herries and Granby) in order that he might be made fit for squeamish throats to swallow.’

Disraeli wrote to his sister Sarah on February 22nd, ‘After much struggling, I am fairly the leader.’ In effect, if not in name, he was now leader of the Opposition in the Commons, though the triumvirate was not formally dissolved until 1851.