Opening of the Sudanese Parliament

The first-ever parliament of the Sudan was opened by the British governor-general, Sir Robert Howe, on January 1st, 1954.

The first-ever parliament of the Sudan was opened in Khartoum by the British governor-general, Sir Robert Howe, who praised the way in which a population unused to democracy had coped with the elections for the House of Representatives and the Senate. Unfortunately, the good fairy did not attend the ceremony.

The Sudan had long been run by British officials under cover of an Anglo-Egyptian condominium, but nationalism bloomed in both the Sudan and Egypt during the Second World War. In 1951 the Egyptians declared themselves sole rulers of the Sudan. The following year, however, the British and Egyptian governments agreed to allow elections for a Sudanese parliament and interim administration under a British governor-general, with the proviso that after three years the Sudanese could decide for full independence. The Egyptians felt confident of controlling the Sudan in cahoots with the Sudanese National Unionist Party.

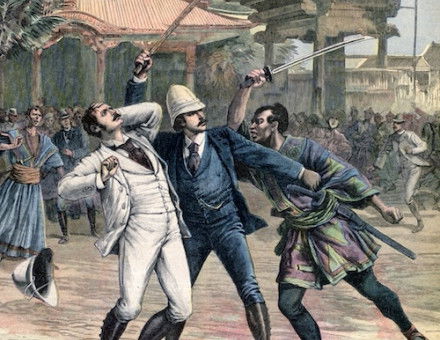

The National Unionists duly won the 1953 election, their leader, Ismail al-Azhari, became prime minister and parliament was adjourned until March 1st while ministers settled into their new posts. When the day came, fighting broke out in Khartoum between pro-Egyptian demonstrators and tribesmen brought into the city by the Umma Party, which wanted total independence and accused the government of aiming at union with Egypt. The British chief of the Khartoum police was one of some thirty-five people killed before the disturbances were quelled and the infant parliament reopened.

Arab-speaking Muslims in the northern two-thirds of the country accounted for 80 per cent of the Sudanese population. The other 20 per cent, in the south, were Nilotic and Sudanic peoples who followed traditional African religions or were Christians. British policy had kept them isolated and, with reason, they feared being swamped. The National Unionist government, now gradually dropping its pro-Egyptian stance, began to transfer the country’s administration into northern Sudanese hands: only a handful of senior civil service posts went to southerners. At the end of 1955 the Sudanese parliament declared for independence and the British finally withdrew. The Muslim northerners took complete control and a guerrilla army of resistance formed in the south, demanding a separate state. The future held occasional brief intervals of parliamentary government between long stretches of military rule and devastating civil war.