Death of Tom Cribb

Richard Cavendish remembers the death of a prizefighter, on May 11th 1848

The parish church of St Mary Magdalene at Woolwich stands on a rise beside the Thames. Near the churchyard’s eastern entrance is a large monument with a lion of dolorous aspect resting its paw on a prizefighter’s belt atop a small urn. Beneath the inscription ‘Respect the ashes of the dead’ lies all that remains of the great bareknuckle champion Tom Cribb, the Muhammad Ali of his day and an English national hero in the Regency period. Sadly, the champion later fell on hard times. Beset by debts, he lived in straitened circumstances, finally dying at the age of 67 in the house of his son, a baker, in Woolwich High Street.

The parish church of St Mary Magdalene at Woolwich stands on a rise beside the Thames. Near the churchyard’s eastern entrance is a large monument with a lion of dolorous aspect resting its paw on a prizefighter’s belt atop a small urn. Beneath the inscription ‘Respect the ashes of the dead’ lies all that remains of the great bareknuckle champion Tom Cribb, the Muhammad Ali of his day and an English national hero in the Regency period. Sadly, the champion later fell on hard times. Beset by debts, he lived in straitened circumstances, finally dying at the age of 67 in the house of his son, a baker, in Woolwich High Street.

Tom Cribb was born in 1781 at Hanham, which is now in the eastern outskirts of Bristol. In his teens he went to London and worked as a coal porter before spending some time at sea. Taking up the prizefighting game, he had his first professional contest in 1805, when he was twenty-four, defeating his opponent over seventy-six rounds. Standing 5ft 10in tall and weighing close to 200lb, he was a shrewd fighter and was soon taken up by the celebrated Captain Barclay, famous for his extraordinary pedestrian feats (which included walking one mile in every hour for a thousand hours in succession). The captain trained and backed Cribb, who after victories which included two defeats of the redoubtable Jem Belcher was recognised as English champion in 1809. Prizefighting had extraordinary prestige in England during the Napoleonic Wars. It was regarded as an expression of national character and attracted numerous aristocratic patrons, while thousands of pounds changed hands in gambling on the bouts.

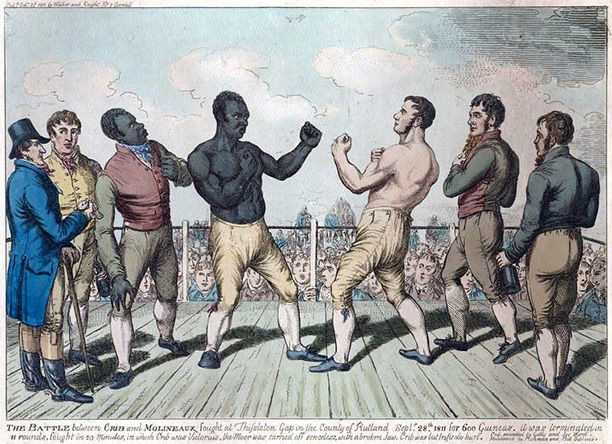

A challenger now appeared from America, a black ex-slave named Tom Molineaux. Cribb met him in 1810 near East Grinstead in a contest which aroused tremendous excitement. It was considered intolerable that an uppity American black should beat the English champion, but Molineaux was a formidable opponent. The Englishman had not trained properly and was badly overweight. He was on the brink of exhausted defeat after twenty-eight rounds when his second craftily saved his bacon by claiming that Molineaux was concealing weights in his hands. The time the referee took to check this false allegation gave Cribb the chance to recover himself and he finally won in thirty-three rounds. The courage and determination both men displayed was hugely admired and a rematch arranged for 1811 at Thistleton Gap in Leicestershire drew more than 20,000 spectators. Cribb had trained seriously this time and the fight was over in twenty minutes. Molineaux’s jaw was broken in the fifth round and though he fought bravely on, by the eleventh round the American was unable to stand. Cribb returned victorious to London, to be greeted by gigantic crowds and an outpouring of triumphant nationalistic effusions.

George Borrow wrote worshipfully of Cribb as ‘perhaps the best man in England … with his huge massive figure, and face wonderfully like that of a lion.’ An admiring Byron encountered him in 1813: ‘A great man! has a wife and a mistress, and conversations well – barring some sad omissions and misapplications of the aspirate.’ The champion retired from the prize ring greatly honoured, but the rest of his life was a miserable anticlimax. He set up in business as a coal merchant, but the venture failed and he turned to keeping a succession of London pubs, culminating with the Union Arms in Panton Street, which in 1839 he had to sell to pay creditors. It is now the Tom Cribb, appropriately decorated with prints and mementos in his honour.