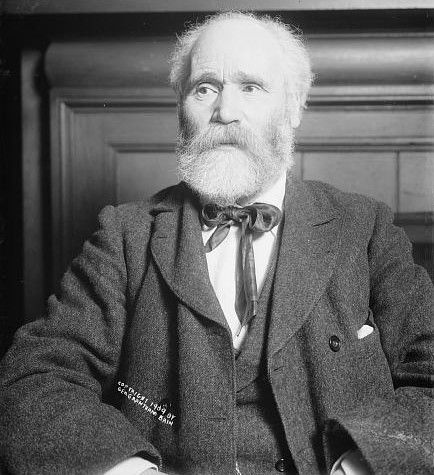

Birth of Keir Hardie

The Labour party's first parliamentary leader was born on August 15th, 1856.

Keir Hardie came into the world in singularly unpromising circumstances. The illegitimate child of a farm girl named Mary Kerr or Keir (herself illegitimate) and, probably, a local miner, he was born in the Scottish hamlet of Legbrannock in Lanarkshire, in the heavy industrial district south-east of Glasgow. One story had him born in the turnip field where his mother was working at the time.

Keir Hardie came into the world in singularly unpromising circumstances. The illegitimate child of a farm girl named Mary Kerr or Keir (herself illegitimate) and, probably, a local miner, he was born in the Scottish hamlet of Legbrannock in Lanarkshire, in the heavy industrial district south-east of Glasgow. One story had him born in the turnip field where his mother was working at the time.The area was pock-marked with mines and ironworks, and with its glowing furnaces and permanent pall of black smoke, was often compared unfavourably to hell. When he was two, the little boy became James Keir Hardie after his mother married David Hardie, a ship’s carpenter. More children followed and the family lived in Glasgow, where David Hardie worked in the shipyards, but an accident kept him off work for months and then there was a long strike in 1866 and he was laid off. He took to drink and the family, desperately hard up, moved back to the Lanarkshire coalfield and a village called Quarter, whose mixed Scots and Irish population had been described twenty years before as ‘rude, vulgar, ignorant and savage in the extreme’.

At the age of ten the young Keir Hardie went to work down a local mine. His job was to regulate the flow of air in the pit through a door, which also had to be opened when a train of coal tubs needed to pass through. It was a grim and frightening place to be, as he recalled later, alone all day, seeing no human face except for the driver of the coal train and listening to the dripping of water and the scamperings of mice. The pit ponies were his friends and he got quite fond of the numerous rats. In time he graduated to being a driver and then to working at the coal face itself. Later he would use his experience in the pit to denounce the rich, the politicians and the establishment, who exploited or neglected those who worked to produce the world’s wealth.

Hardie had little or no schooling, but he did somehow learn to read. Encouraged by his mother, he went on to educate himself, reading history and literature, and especially admiring Carlyle. In the darkness of the pit, he taught himself shorthand by the light of a miner’s lamp. Presently he became active in the temperance movement and as a Christian lay preacher, both of which gave him experience in public speaking.

Hardie got involved in the burgeoning miners’ union movement and was fired. He started writing for a Glasgow paper and in 1880 was appointed secretary of the Ayrshire miners’ union. In politics he was at first a Liberal, but his experiences in the mine and the union drove him further to the left and by his thirties he was demanding the nationalisation of the mines and the destruction of the whole capitalist system. In 1893 he founded the Independent Labour Party to get working-class Members of Parliament elected separately from the Liberals and in 1900 took a leading role in setting up the Labour Representation Committee, which became the Labour Party in 1906. An MP himself in 1892-95 and again in 1900-15, he was leader of the parliamentary party in 1906-07. It was a role he disliked, his MPs did not consider him a good leader and historians disagree about the extent to which he was really a socialist, but one of his biographers, Keith Morgan, called him Labour’s ‘only acknowledged folk hero’. He was fifty-nine when he died in Glasgow in 1915.