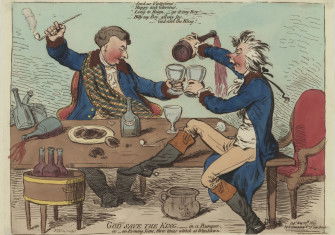

The Music of the Napoleonic Era

The power and perils of reconstructing the music of Napoleon's time.

Music was a key part of Napoleon’s representation of himself and the construction of his legend. In recognition of this, the Musée de l’Armée in Paris hosted a cycle of 14 concerts this year to celebrate Napoleon in his own words and music. One of these concerts featured music commissioned by Napoleon, written about him, or loved by him. Most of the music had lain, unused, in the archives for years, until Peter Hicks, under the auspices of the Fondation Napoleon, located and transcribed it, reconciling different versions. The aim was to convey the sounds of the Napoleonic era as contemporary audiences might have heard them.