Kashmir: Prisoner of History?

Caught between the antagonistic states of India and Pakistan, Kashmir is stuck in geopolitical limbo. Its location – and its history – threaten to keep it there.

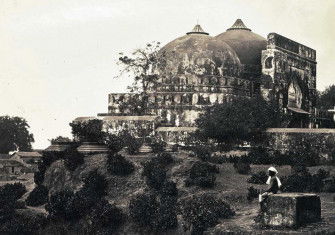

Kashmir, a small valley in the Himalayas, plays an outsized role in the national imaginations of both India and Pakistan. Formed by the river Jhelum and its tributaries, and measuring a mere 89 by 25 miles, the Kashmir Valley has historically been a crossroads between Central and South Asia. The region has been an independent kingdom, a province within the Mughal, Afghan, and Sikh empires, a princely state within British India, and, latterly, a state within India.

The Kashmir Valley’s strategic location, physical beauty, and distinct religious culture have been of critical importance to the political entities of which it has been a part. But its special status has intensified dramatically with the conflict between India and Pakistan over the region since 1947, in which each state has placed Kashmir at the heart of its nationalist aspirations. The moment and process of decolonisation casts a longer shadow in Kashmir than perhaps anywhere else in the Indian subcontinent.