England Through Camden’s Eyes

While we return again and again to the proto-historians of the classical world, we neglect those pioneering figures closer to us in space and time. Why is this, wonders Mathew Lyons?

I have recently been reading Tom Holland’s superb new translation of Herodotus’ Histories. I am by no means an authority on classical writers, but I have always enjoyed Herodotus. He is so irrepressibly inquisitive and, in every sense, a pleasure to read. Holland has always been a fine writer, both in the clarity and subtlety of his intellect and the spare, evocative lucidity of his style. Reading the two together, as it were, has made me more aware than ever before of the exquisite tension between writer and translator.

I have also wondered why we still read Herodotus, aside from the gifts of the translators he attracts. It is partly a question of style, I think, partly of intellectual attitude and partly his distinctive collation of data. We are delighted when we believe him to be accurate; but accuracy is not a standard we demand of him. If we want a reliable account of the classical world, we read a modern historian. Herodotus we read for a first-hand sense of the world as it was understood and experienced by its people.

We do not, though, apply the same standards to our own antique historians. I am not wholly sure why.

Since I encountered him first at university, I have always been an admirer of William Camden, author of the Britannia, first published in 1586 in Latin and revised a number of times over his lifetime. He oversaw an English translation in 1610. It is a volume that lays claim to being the first truly great work of English history, but it is also so much more than that. It is a work of historiography, linguistics, chorography and numismatics, too. Its primary organising principle is the pre-Roman English tribes – the Belgae, Iceni, Trinobantes and so on – and, within those, the county. Chapter by chapter, Camden pieces together landscape and language, history and archaeology, research and observation, always as aware of the deep and hidden history of the past as he is the visible innovations of the present.

Camden has not only taught himself Anglo-Saxon and Welsh: he has studied a dauntingly vast range of archival material; he has read every authority; he has talked or corresponded with every expert; and, importantly, he has travelled to every part of the country. We see England through his eyes as we understand it through his learning; the flux of both history and historiography becomes startlingly present. He is everywhere in his work, sifting, evaluating, commenting, observing, weaving together what we would now regard as wildly disparate disciplines. It is a mighty testament to the historian’s greatest asset: a restless curiosity. This is not to say Camden is always right, but, as with Herodotus, he is usually wrong in thought-provoking, revealing and entertaining ways.

In the age of the Internet and the car, his industry is exhausting. For the 1570s and 80s it is almost unbelievable and it is a sobering thought that he did all this and saw the Britannia into print by the age of 35.

It is even more so, perhaps, when you consider that the study of Britain’s antiquity was by no means highly regarded as an intellectual pursuit. ‘Some there are’, he admits, ‘which wholly condemn and avile this study of antiquity as a back-looking curiosity.’ But part of Camden’s achievement was simply to make the study of history intellectually credible in England and this rebuke to his critics is magnificent: ‘If any there be which are desirous to be strangers in their own soil and foreigners in their own city, they may so continue and therein flatter themselves.’

I plan to memorise that and repeat it next time someone questions me about the value of history. We could do with some of his scholarly defiance.

Yet who reads him today? We read classical historians, flawed though they are; but we disdain the great historians of our own culture and tradition. This is a loss to us culturally as a nation and a loss to us professionally as historians.

The study of antiquity ‘hath a certain resemblance with eternity’, Camden wrote. It is time we rescued him from it.

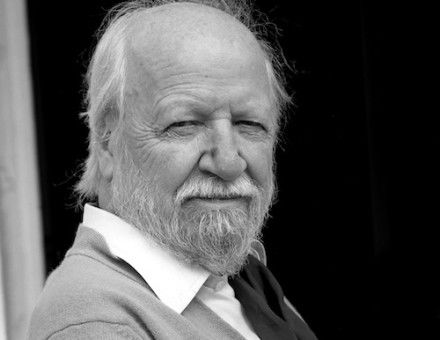

Mathew Lyons is author of The Favourite: Ralegh and His Queen (Constable & Robinson, 2011).