William II of England: The Sin King

The medieval court of William Rufus, son of William the Conqueror, was known as a ‘brothel of male prostitutes’.

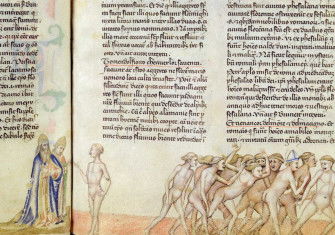

A group of floppy-haired youths flaunt their bodies and flirt with one another. A religious leader in his sixties berates them for their behaviour and calls on them to repent. We might be forgiven for thinking this incident is set in the present day, but it was reported by a monk describing the court of William II in the 1090s.