Edward: The Lost Tudor

Son of a queen and uncle to the king who founded a dynasty, history almost forgot Edward Tudor. Why?

In about 1430, Katherine de Valois, widow of Henry V, secretly married a young Welsh squire named Owen Tudor. Their union, which was not widely known until after her death in 1437, was the beginning of a dynasty that would rule England for over a century.

During her widowhood Katherine had spent most of her time at Hertford Castle, given to her in 1418 by her first husband. Her young son, Henry VI, who succeeded to the throne at only nine months old, spent some of his formative years there, although he was largely removed from the supposedly dangerous influence of his French mother. It was probably here that Katherine met her second husband – he may have been a member of her household. Here, too, or nearby in Hertfordshire, the queen bore several children, the precise number of which has been the source of debate ever since. It is finally possible to unravel centuries of misunderstandings and to reinstate Katherine and Owen’s third son, Edward Tudor, to his rightful place in the early history of the family.

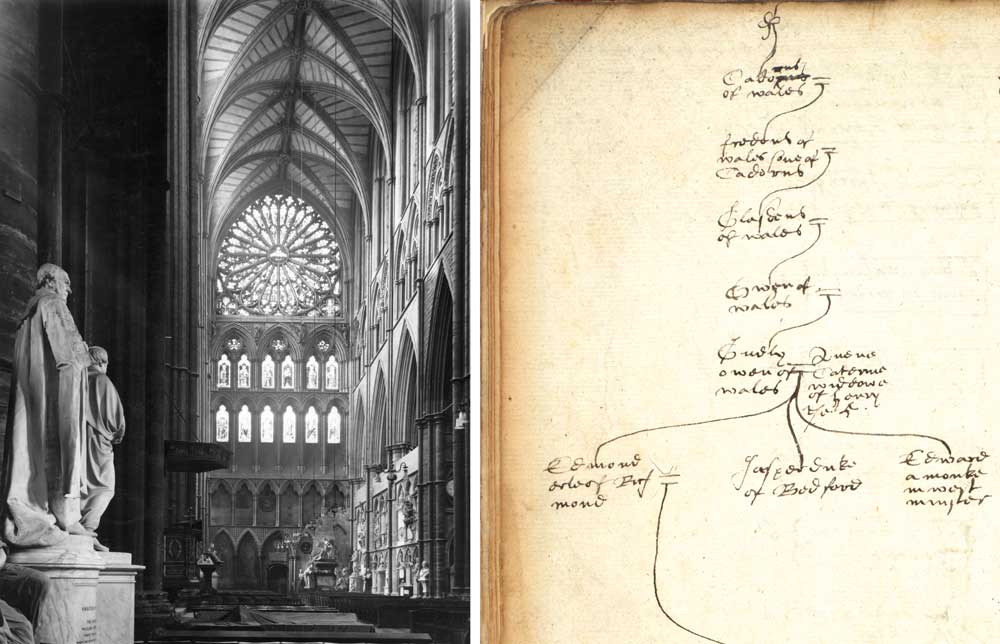

Family tree

Writing in the first years of the 16th century, the Italian historian Polydore Vergil stated that Katherine and Owen’s two well-known sons – Edmund Tudor (father of Henry VII) and Jasper Tudor – were followed by a third, unnamed child, who had entered the monastery at Westminster Abbey ‘and lived not longe after’. The couple also had a daughter, Margaret, who apparently became a nun. Vergil was writing at the instigation of Henry VII and was a prominent member of the English court, so might be expected to have been able to establish the facts.

When, nearly a century later, the historian William Camden published the first guide to the monuments in Westminster Abbey, he recorded, among the descriptions of the tombs and inscriptions of kings and queens, nobles and senior ecclesiastics, the burial spot of Edward, a monk of Westminster, son of ‘Oen Theodori or Tidder’ and Queen Katherine, widow of Henry V. ‘He was the brother’, Camden tells us, ‘of Edmund, Earl of Richmond, and uncle of Henry VII’. Camden decorated his own copy of the book with the coat of arms of the Tudor family. The site of Edward’s burial was, Camden reveals, in the chapel of St Blaise, by what is now known as Poets’ Corner.

This would seem to provide fairly clear evidence for the existence of Edward Tudor. But, not long after Camden’s book appeared, confusion was introduced when Francis Sandford, in his history of the kings of England published in 1677, referred to the third son of the founder of the Tudor dynasty as being named Owen. This suggests that whatever marker or memory of the location of Edward Tudor’s burial spot at Westminster that had existed had been removed or forgotten by the late 17th century. Sandford himself was probably confused after discovering the record of the death, in 1501, of an individual named Owen Tudor, towards the costs of whose burial Henry VII paid 61 shillings the following year. Sandford’s statement was then regularly repeated, eventually leading in 1873 to the historically minded Dean of Westminster, Arthur Stanley, having a stone put into the floor of the south transept of the abbey commemorating, among others, ‘Owen Tudor, monk of Westminster, uncle of Henry VII’.

Who’s who

Ever since the publication of Sandford’s history, historians of the early Tudors have become increasingly muddled in their references to the children of Owen Tudor and Katherine de Valois, the half brothers of Henry VI. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography reflects the confusion. It states that the couple had ‘three sons (Edmund Tudor, Jasper Tudor and Owen)’. The last of these, we are informed, ‘is also referred to as Edward’ and ‘became a Benedictine monk at Westminster Abbey’. Nothing more is apparently to be said about him. A recent biography of Owen Tudor also conflates two individuals named Edward and Owen in a forlorn attempt to resolve the various references.

The only constructive attempt to solve the mystery of his identity by actually looking at the archives of Westminster Abbey was made by E.H. Pearce, a canon of Westminster, in his dictionary of Monks of Westminster, published in 1916. Having acknowledged that Camden’s reference names the third Tudor son ‘Edward’ not ‘Owen’, Pearce scoured the records of the abbey for references to a monk named Edward who might fit the bill. Pearce was aware that it was common practice for monks, on entering the community as novices, to drop their birth surnames and adopt a different one in recognition of their new life ‘in religion’. These new names were very often based on their place of origin. The only realistic candidate he could find was a Brother Edward Bridgewater, who entered the monastery in 1465-66 and died six years later. ‘The only other Edward on our list at this period’, wrote Pearce, ‘is Edward Boteler, who was transferred to St Milburga’s Priory at Wenlock; so we are left with the option of identifying Edward Bridgewater with Camden’s Edward Tudor’. Pearce’s supposition has been repeated ever since (sometimes with the caveat that there was very little evidence to support it). But Pearce was inexplicably looking in the wrong era, and there is a sense that he did not seem entirely convinced of Edward Tudor’s existence at all.

Edward Hertford

Newly discovered evidence can certainly put the issue of whether or not Edward existed to rest. In 1516 another Westminster monk, Brother Thomas Gardyner, drew up a pedigree of the Tudor family down to Henry VIII. In it, he listed under the children of Owen and Katherine a third son, ‘Edwarde a monke in westminster’. This evidence, roughly contemporary with Vergil, predates Camden by nearly a century. And Thomas Gardyner was in a position to know. Not only was he himself a monk of Westminster Abbey, he was also the illegitimate grandson of Edward Tudor’s brother, Jasper, and was actively engaged in recording and promoting the kingship of Henry VIII and the Tudors.

If we accept the evidence of Polydore Vergil, Thomas Gardyner and William Camden that Edward (not Owen) Tudor is likely to have been a real figure, can he actually be identified among the monks known to have been at Westminster in the 15th century? As a general rule, novices entered the monastery aged about 15. Owen and Katherine married around 1430 and Edward’s older brothers, Edmund and Jasper, were born in about 1430 and 1431 respectively. Since Katherine died in 1437, Edward must have been born between 1432 and 1437; he is therefore likely to have entered the community in the late 1440s or early 1450s. So, Pearce’s identification of him with someone who entered the monastery in 1465, nearly 20 years later, is odd – particularly as the real identification was right in front of him.

Among the novices at the monastery at Westminster in 1447 is listed ‘Edward Hertford’. Edward Hertford is barely mentioned in the other records of Westminster Abbey, beyond appearing in occasional lists of monks who received their annual shares of income from various foundations. Nothing more is known about him, except that he is not recorded after 1451-52. This almost certainly relates to the date of his death and corresponds precisely to Polydore Vergil’s description of him having died soon after entering the monastery. And, of course, the name adopted by the young novice also makes perfect sense; his mother spent most of her later years in seclusion in Hertfordshire. Katherine’s son Edmund was supposedly born at the Bishop of London’s palace at Much Hadham in Hertfordshire, and Jasper soon after at the Bishop of Ely’s manor of Hatfield. In their youth, the two boys were sometimes known as Edmund of Hadham and Jasper of Hatfield. It was probably at Hertford Castle that Edward, Katherine and Owen’s third son, was born and raised.

In 1443, six years after Katherine’s death, Henry VI enjoyed Christmas at Hertford with his half-brothers. And so the name ‘Hertford’ was adopted by the teenage Edward when he was dispatched to Westminster, doubtless at the direction of the king together with his father Owen Tudor. Hertford Castle was passed on by the king to his wife, Margaret of Anjou.

Owen’s fate

And what of the later Owen Tudor whose death in 1501 helped cause so much confusion? In fact, he was not a monk at all. On 2 November 1495 Henry VII granted letters of denization (a formal grant allowing him to become English) to ‘Owen Tydur, esquire for the body, a native of Wales’ and his children. Esquires of the body were personal attendants to the king, usually six in number at any one time, and so in a position of great honour and potential influence at court. Owen Tudor was clearly much liked by Henry VII. In 1496 the king gave him a ‘reward’ of 40 shillings, with another similar gift two years later. He may have been the ‘master owen’ who was given 33 shillings and 4 pence for ‘riding with letters into Wales and Shropshire’ in 1497.

But this Owen did not live long after. As we have seen, in 1502 the king paid towards the costs of his funeral. He died the year before and was buried in the churchyard of the parish church that sits immediately adjacent to Westminster Abbey, St Margaret’s. The churchwarden’s accounts record the ringing of a knell at his funeral and the payment for him to be buried in the churchyard.

All of this suggests that Owen Tudor was probably a relation of Henry VII. He was possibly an illegitimate son of Jasper Tudor, and therefore the king’s cousin; he received his letters of denization a month before Jasper’s death. The man who was directed by the king to settle Owen’s funeral costs, Morgan Kidwelly, was also an executor of Jasper Tudor. But it is not possible to be sure.

Lost Tudor

We will never know the precise reason for Edward Tudor’s removal from Hertford to the closed community at Westminster, nor of his death only four years later. His brothers became great barons of England, and his nephew, Henry, the first Tudor king of England. Such an untimely death at just 20 years old suggests in Edward a frailty that may have been born of chronic illness or disability, either of which might have prompted a removal to the cloistered world of Westminster Abbey. But outbreaks of epidemic diseases were commonplace. Plague, dysentery, influenza and the sweating sickness all killed untold numbers. Edward Hertford does not feature in the surviving accounts of the abbey’s infirmarer, the monk who had charge of his sick brethren, suggesting that there had been no regular requirement for care.

His early death, as well as the monastic habit of name-changing, almost threatened to remove him from history. Only brief records enable us to unpick his story and reconcile the youthful Edward Tudor, son of a queen and half-brother and uncle to kings, to the Westminster monk, Edward Hertford, whose four years in the monastic community left precious little evidence.

Matthew Payne is Keeper of the Muniments at Westminster Abbey.