Pilgrims and Poverty in Renaissance Rome

Rome welcomed and tended to the vast numbers of pilgrims who arrived in the 16th century, but its attitude to its own poor could be very different.

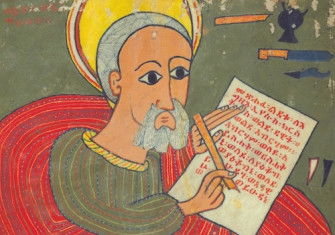

An unprecedented number of pilgrims travelled to Rome for the last two jubilees of the 16th century. Held every 25 years, jubilees were a rare opportunity for the faithful to earn plenary indulgences that absolved them from the ‘temporal punishment’ for sins that had already been forgiven. The sight of people from so many nations joining together in worship symbolised the papacy’s renewed strength after the great turmoil and division of the Reformation. A commemorative print gives an impression of the crowds at the opening ceremony in St Peter’s Square on Christmas Eve 1574. Pope Gregory XIII is carried aloft in a sedan chair towards the Holy Door of the basilica, surrounded by a great throng of pilgrims and spectators. Over the following year, reports suggested that as many as 400,000 people came to the city, a remarkable figure given that its entire population was around 80,000. In 1600 this grew to an estimated 536,000 pilgrims, from countries as far afield as Armenia, England, Poland, and Spain.