‘The Strange and Tragic Wounds of George Cole’s America’ review

In The Strange and Tragic Wounds of George Cole’s America: A Tale of Manhood, Sex, and Ambition in the Civil War Era, Michael deGruccio discovers a generation betrayed by the fight for freedom.

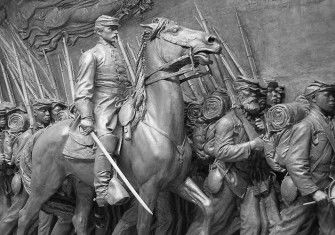

This is a study of ambition. Or rather ambitions. It is the product of those of its author, Michael deGruccio, whose main ambition, now achieved, was to ‘land a job as a history professor’, but also, and as a route to that end, to write ‘an unconventional narrative’ about America’s Civil War era. The subject of the resulting narrative is an individual Civil War soldier, George W. Cole (1827-75), whose desperate ambitions for financial security, social recognition, and military advancement rendered him, at least in part, the instigator of his ultimate downfall. As commander of the 2nd United States Colored Cavalry, part of the Army of the James, Cole’s professional ambitions were largely linked to those of the many African Americans seeking to break the bonds of enslavement and create a stable life for themselves and their families. But they found their ambitions shattered by the relentless and thoughtless juggernaut of a military machine that quite literally used them, abused them, and then threw them away. The Strange and Tragic Wounds of George Cole’s America is, in its author’s words, ‘a tale about American family strained by war and worldly ambition’. More than that, it is a meditation on the ambitions of the American nation over the course of the 19th century, as it navigated its way towards modernity via a route that proved, for many of its citizens, to offer a future that failed to live up to past promises.

The result of all this is a smorgasbord comprising a collection of individuals each of whom, in their own way, exemplifies the particular challenges that faced 19th-century Americans. Centre-stage is accorded Cole the soldier, his Black troops, his wife, and her (possible) lover. But around them swirl a cast of supporting characters, some of whom, Cole’s children, for example, are little more than noises off. Others, such as Cole’s politician brother Cornelius and sister-in-law Olive have rather more than walk-on parts; especially Olive, who often seems to be the sole voice of reason. And although the book is pitched as one about a murder absent any particular mystery since it was committed in public, it is far more about those many men who never returned whole from the Civil War’s battlefields and those who never returned at all. It is peppered with vignettes detailing the wounds of war, the perils of childbirth, and, at some length and in greater detail than either, the horrific racism exhibited by some white officers, although not Cole himself, towards Black troops.

If ambition is the driver of deGruccio’s narrative, emotion forms the core of his analysis: the author’s own emotions about his nation, Cole’s emotions inherited from the nation’s revolutionary past, and more general 19th-century fears of a future that promised greater equality and freedom for women and African Americans alike, and the greed, raw racism, and its resultant cruelties that accompanied the implications of both. Cole’s antebellum story was typical of many in the expanding nation. ‘On lands brutally stolen from Indians’, deGruccio writes, ‘American children grew hungry for a prosperity their parents had never known’. Worldly ambition was drummed into them by church and school alike. It was the cornerstone of the American Dream, but it did not play out for George and Mary Cole, nor for many others.

One telling example that deGruccio highlights was the potential impact of the Married Women’s Property Acts that became law after 1848. Left money by her father, Mary Cole found herself unable to keep her legacy separate from her husband. It was this that most likely drew her to Luther Harris Hiscock, a lawyer with a reputation for securing women’s estates, her future purported lover, and the victim of her husband’s Derringer in the summer of 1867. An unwillingness to accord his wife her financial due was, arguably, the first domino in a chain that led to murder. But the outcome might not have been terminal for Hiscock had the war years not inflicted so much damage on Cole, both physically in the form of his injuries, and psychologically in his desperate desire to be promoted to general and his ultimate frustration at only achieving brevet status (title but not pay or privileges). DeGruccio fully admits that he is piecing together a story and an explanation from such fragments of evidence, such as court records and family correspondence, as survive.

The stronger evidence for Cole’s life and experiences is contained in the many records created by military and medical authorities over the course of the Civil War. Much of it makes for truly saddening reading, particularly in deGruccio’s sustained analysis of the experiences of Black troops under Cole’s command; not for anything Cole did, but for what he was unable to prevent others doing. The attempted murder by Lieutenant Robert Dollard of African American sergeant Washington King, and then the actual murder by Cole’s protégé Edwin R. Fox of African American soldier Henry Edwards, were simply the extremes of an exploitative military and racial hierarchy that gave little thought and accorded little care to those Black soldiers who had put their lives on the line for the Union.

The death of many of these men in Texas at the war’s end from scurvy, an entirely preventable disease by that time, is detailed in Margaret Humphreys’ 2008 study, Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the Civil War, which deGruccio draws on. But as he shows, the federal government was hardly more kind to any of the wounded who returned from the war. Following the murder, Cole’s defence emphasised his status as a wounded veteran, who had suffered for his nation, who had left for war while others, such as Hiscock, had remained at home to build business and fortune. As far as saving Cole from the gallows went, it was a successful strategy. But by the end of this ambitious and imaginative book – which its author admits is a ‘bleak story’ – one wonders about the ideals of equality and freedom that underpin a nation that exacted such a high price from those prepared to fight for them.

-

The Strange and Tragic Wounds of George Cole’s America: A Tale of Manhood, Sex, and Ambition in the Civil War Era

Michael deGruccio

Johns Hopkins University Press, 352pp, £27.50

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Susan-Mary Grant is Professor of American History at Newcastle University.