Get Out: Excommunicated in Medieval England

In 13th-century England excommunication was akin to spiritual leprosy. How did it work?

In 1229 the people of Dunstable declared that they would rather go to hell than submit in a dispute over taxes. This was not mere rhetoric: their clash over tolls was with the town’s priory, and they were excommunicated for their refusal to pay. Excommunication, they would have been told throughout their lives, ultimately resulted in eternal damnation. The theology was more nuanced, and absolution was always a possibility (even posthumously from 1198), but the average layperson in 13th-century England was taught to fear the spiritual effects of expulsion from the Church.

Didactic examples, typically used to liven up sermons, described miracles in which excommunicates were struck down by injury or death. Others explained that those who died excommunicate suffered – in one example ‘boiled’ – in hell. Their corpses were not permitted to be buried in consecrated ground; they could be, and were, exhumed, disposed of outside the cemeteries they had been illicitly polluting. Clergy concluded excommunication ceremonies by extinguishing candles that represented the souls of those condemned.

Excommunication was surely a terrifying prospect. Yet the received wisdom among academics is that, while it was the medieval Church’s most severe sanction, it was an ineffective one. It is certainly true that there are a number of high-profile excommunicates who were apparently unaffected by it. King John, excommunicated for three years between 1209 and 1212 by Pope Innocent III for refusing to accept Stephen Langton as archbishop of Canterbury, is the famous example. Such powerful figures potentially suffered more serious consequences – John eventually reconciled with the pope in response to the dual threats of deposition and a French invasion – but also wielded power that might enable them to weather ecclesiastical censures.

Further down the social scale, however, people lived as excommunicates for months and years or sought absolution only to be subsequently, in some cases frequently, re-excommunicated. It is worth pointing out that canon law required that sinners be warned before being excommunicated, so that the pious or fearful could avoid being sentenced in the first place. Yet it is clear that excommunication did not automatically induce offenders to alter their behaviour.

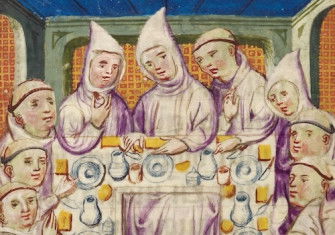

One reason was that action to avoid an afterlife in hell need not be taken immediately: absolution was always to be given to those who repented, especially if they were on their deathbeds, when anyone at all could theoretically provide it. Yet living as an excommunicate created numerous difficulties. As the name suggests, it forbade communication with other Christians. Those under the ban could not receive the sacraments and they could not attend church services, as one might expect. But excommunicates were also meant to be completely barred from the quotidian life of their fellows. By the 13th century various exceptions had been admitted – you did not have to ostracise your spouse, for instance, and a starving person could accept food from an excommunicate – but their exclusion was theoretically severe. Excommunicates had no legal standing in either secular or ecclesiastical courts. Their friends and neighbours were not permitted to talk to them, eat or drink with them, or trade with them. The sanction was in fact contagious, a spiritual leprosy: if someone conversed with an excommunicate, they would themselves incur a lesser form of excommunication. The unrepentant, like an infected limb, had to be amputated from the healthy body of Christian faithful.

This theory did not mean excommunicates all suffered complete exclusion. Some, such as the people of Dunstable, were excommunicated along with others, and presumably communicated with each other. Ralph, a wine merchant from Honey Lane in the City of London, had managed to live as an excommunicate for over three years in 1300. Judging by the letter sent to the mayor and community of the city, which noted that people were impudently associating with this ‘representative from the devil’ and putting themselves in danger of eternal malediction, Ralph had succeeded in living fairly normally. In addition to the typical injunctions not to eat or drink with the offender, the citizens were urged not to have commercial transactions with him, which implies his wine business had survived intact. It is impossible to know why Londoners failed to treat Ralph as an excommunicate, but it is possible that his offence, failing to properly execute a will, was not seen as particularly serious.

However severe the ultimate consequences of excommunication, it was not reserved only for the most serious crimes. It was used routinely by churchmen who were unable to use physical force to enforce their orders. Unscrupulous clergy using the power to excommunicate unfairly, despite whatever procedures guarded against that, undermined the sanction. Appeals on the grounds of justice were not permitted, which could result in a catch-22. In the 1220s Alice Clement lost her 40-year struggle to claim her inheritance because, as an excommunicate, she had no legal standing. She could not seek absolution because her offence was being an apostate nun: admitting her offence would mean returning to the nunnery at Ankerwyke in Berkshire which, she claimed, she had been unwillingly forced into as a child. Nuns could not inherit.

A century after Alice’s struggles, another runaway nun demonstrates another unpleasant experience for excommunicates: bad press. Joan of Leeds was so desperate to escape her nunnery that she faked her own death. Once this had been discovered, her excommunication was publicised throughout the diocese of York. The archbishop did not pull his punches: the faithful were informed every Sunday and feast day that Joan had left her convent in order to enjoy ‘shameless enticements of the flesh’, exchanging poverty and obedience for lust. These vehement denunciations, broadcast across sometimes very large geographical areas, and which gave only the Church’s version of events, were experienced by all excommunicates. How else would people know who to ostracise? Many complained bitterly about these public condemnations, which might have consequences long after they had sought absolution. The obvious need to explain who was excommunicated and why, coupled with the network of parish churches that spread throughout Europe, provided the Church with a tool of mass communication and, in some circumstances, of propaganda.

As for the people of Dunstable, their obstinacy did not last. Although there was a great deal of conflict before an agreement was reached between them and the prior, like the vast majority of excommunicates, they eventually made peace with the Church.

Felicity Hill is Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of St Andrews.