‘Liverpool and the Unmaking of Britain’ by Sam Wetherell review

In Liverpool and the Unmaking of Britain, Sam Wetherell discovers a city of slavery, ships, soccer, and socialism, whose fortunes rose and fell with the tide.

Liverpool, we often hear, is a city apart; ‘Scouse not English’, as the local saying goes. Throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Irish heritage of many Liverpudlians helped forge a civic culture and politics distinct from the rest of the country – so much so that for 44 years one of the city’s constituencies returned the only Irish Nationalist MP on mainland Britain. Its position as a great trading hub at the mouth of the River Mersey, looking out onto the Irish Sea and the Empire beyond, gave its economy a character unlike the industrial lands to its south and east. Yet, paradoxically, as Sam Wetherell notes in this fascinating and quietly iconoclastic book, such apartness both created the conditions for, and heightened, Liverpool’s status as a bellwether for the rest of the country, perhaps even the world.

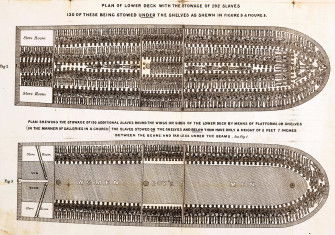

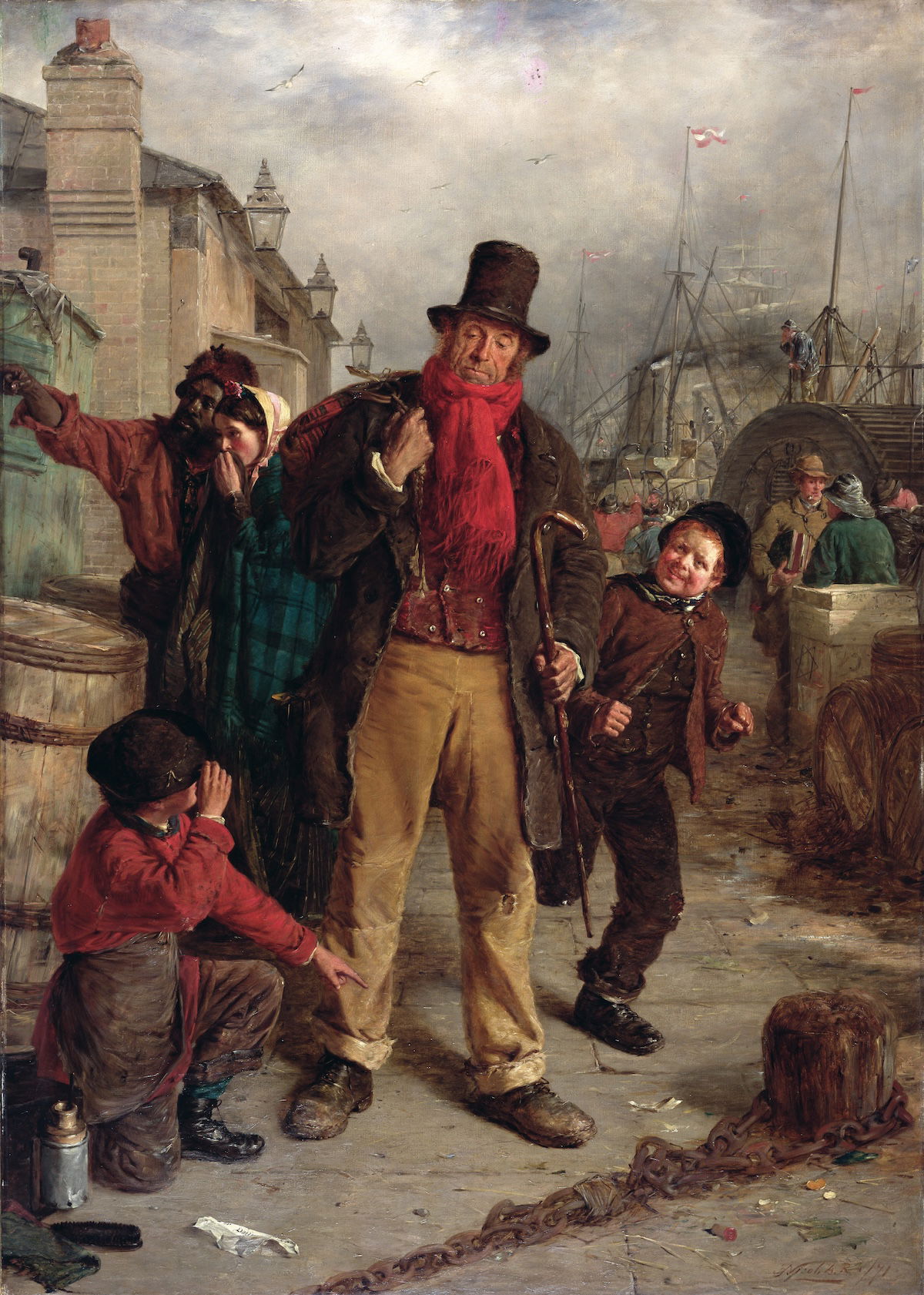

Modern Liverpool began in 1648, Wetherell writes, when 30 tonnes of American tobacco landed on the banks of the Mersey. From there, its rise was precipitous; 200 years later some 40 per cent of the world’s trade would pass through its ports and docks. But it was slavery, above all, that dominated the city’s economy. By 1807, when the trade was abolished, more than 1.1 million enslaved people had been transported by the city’s ships. Even abolition couldn’t stop the city’s commercial dominance – by the early 20th century it was larger and richer than any English city other than London.

Yet, by the end of the Second World War, when Wetherell’s narrative begins, the global engines of trade were beginning to splutter. The city’s economy had long been prone to sharp downturns during moments of crisis, and those who were hit hardest by these buffeting winds of economic competition were the thousands of workers on the city’s docks. Even the wartime minister of labour, Ernest Bevin, and his scheme for regularising dock work, turning what had long been casual and precarious work to an industry with a permanent workforce and a guaranteed minimum weekly wage, wasn’t enough to place its economy on an even keel.

Decolonisation and the shift away from Empire quickly undercut Liverpool’s trade supremacy. Sensing what was to come, the postwar decades saw state-led attempts to diversify Liverpool’s economic base. And it was the car, that gleaming symbol of industrial modernity and individualised consumption, that was to be at the forefront. During the 1960s three of the ‘big five’ automakers opened new factories on Merseyside, and some six million tonnes of oil passed through the region in 1962 alone. The dominance of the auto industry was joined in these years by a redevelopment of the city away from the dense inner-city slums and warehouses that once characterised its urban fabric to new suburban estates on the city’s periphery. With this came a new cultural ascendency too, as the Beatles dominated the charts across the Atlantic and Bill Shankly’s Liverpool FC conquered all on the football field.

This period of relative modernist prosperity was, however, short-lived. Containerisation further decimated the docks, its workforce dropping from 10,500 to just 2,000 between 1971 and 1983, and the new industries of the suburban hinterland were battered by the global downturn of the 1970s. If the 1960s was the decade of Merseybeat, all guitars and mod suits, the 1980s was the era of Alan Bleasdale’s Boys from the Blackstuff. In just three years in the early 1980s, Merseyside saw 384 factory closures, taking with them 25,000 jobs. The city had, it seemed, outlived its economic purpose.

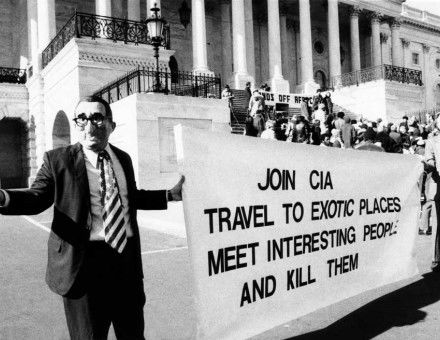

The Thatcherite decade saw some of the most famous, and tragic, events in the city’s history: the Toxteth uprising, the Hillsborough disaster, and the rise and swift defeat of Liverpool’s radical Militant-led council. It is to Wetherell’s great credit that he gives these already familiar events new life. A gifted storyteller, he is able to place the events in Toxteth in July 1981 in both the long arc of Liverpool’s Black community as well as the decades of police and state racism. For Wetherell, quoting Stuart Hall, these years were marked not by the expansive, aggressive racism of Liverpool’s imperial maritime economy, but by ‘declining social formation’, to which the events of 1981 were ultimately a reaction. In the uprising, in which thousands of young people turned out to confront the massed ranks of police armed with riot shields and tear gas, we can see a glimpse, however incoherent and fleeting, of potential post-imperial solidarities rather than the mindless violence of tabloid mythologising.

Likewise, the story of Militant, as well as the belated rise of Labour dominance in the 1950s, is given a subtle and compelling revisionist spin. Unlike the standard narrative, developed from Neil Kinnock’s famous 1985 Labour conference speech, which sees Militant’s downfall coming from its excess of radicalism (‘impossible promises … with far-fetched resolutions … pickled into a rigid dogma’), Wetherell roots its failure in the absence of radicalism. The council’s ambitious house-building schemes resulted in vast rows of single-family houses, a kind of ‘muted Trotskyist suburbia’, which along with its open hostility to the rising tide of Black and feminist organising in the city helped to undercut its support.

In response, Michael Heseltine, the self-declared ‘Minister for Merseyside’, let a kind of free-market experiment in supply-side urbanism run through the city. Liverpool, with its swathes of now redundant industrial land, was soon pocked with special economic zones, overseen by remote development corporations, each enacting radical experiments in economic deregulation. Liverpool was reborn as an entrepreneurial city of the kind now familiar across the world. If it had once been ‘a dying star’ whose thousands of manufacturers beamed out goods to the world, it was now more like a ‘black hole, a vacuum into which tourists and finance would be sucked’. The remodelled Albert Docks, an entertainment and tourist hub in place of a dockyard, stands as a symbol of the changes wrought. In this, and much else, ‘Liverpool’s history’, Wetherell writes, ‘is a prophecy’.

-

Liverpool and the Unmaking of Britain

Sam Wetherell

Apollo, 448pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

John Merrick is the editor of Raphael Samuel’s Workshop of the World (Verso, 2024).