World Wide Weber

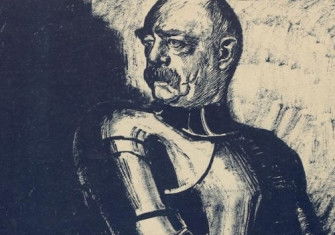

‘Politics as a Vocation’, a speech made in 1919 by the German sociologist Max Weber, can lay claim to being one of the most influential political statements of the 20th century. Amid global crisis and uncertainty, it remains as relevant as ever.

Max Weber’s extraordinary lecture ‘Politics as a Vocation’ is one of the defining intellectual moments of the 20th century. It is best known today for Weber’s supposed description of the state as possessing ‘a monopoly of violence’, but its true importance runs much wider and deeper than that.

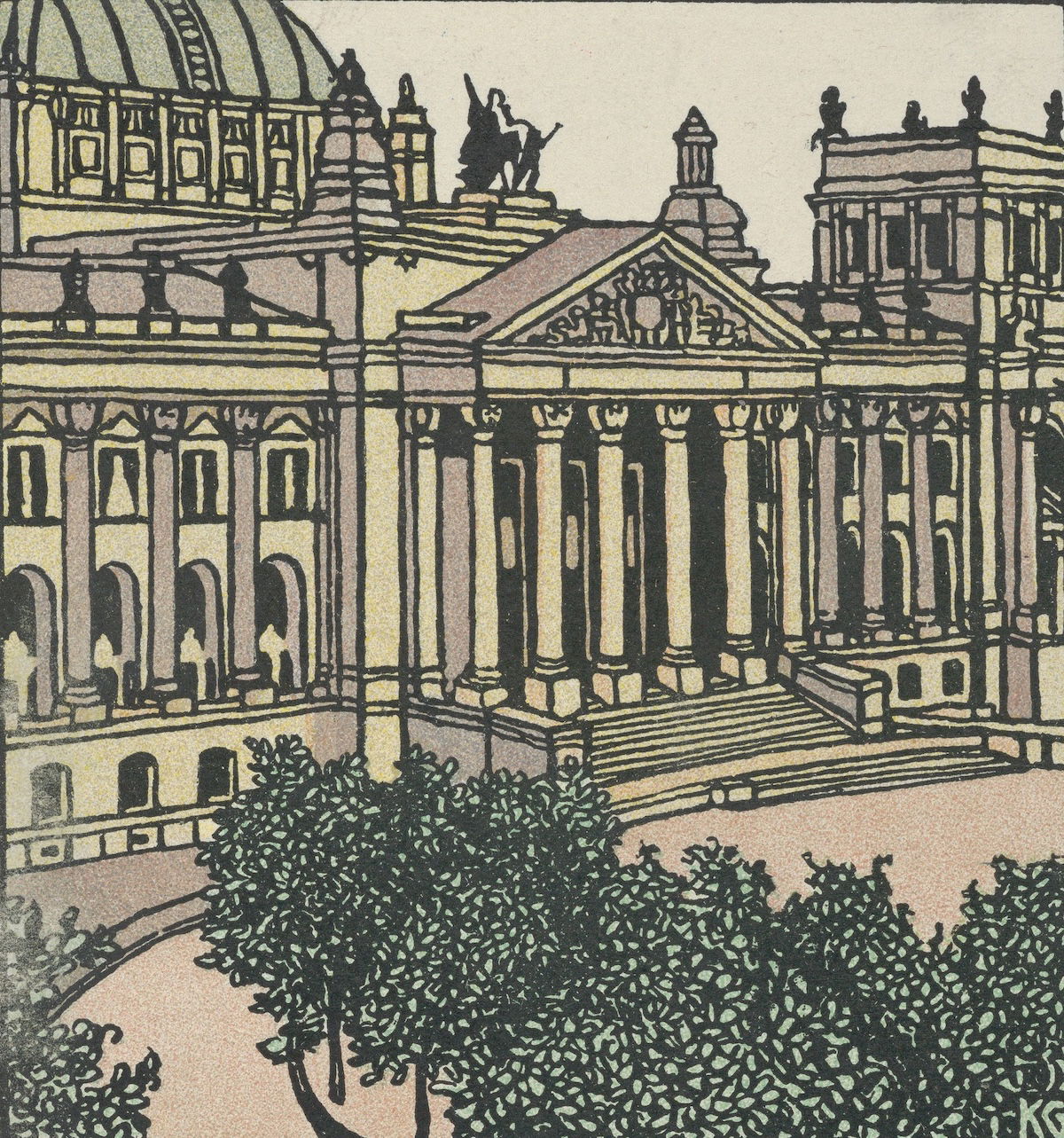

To give the lecture at all was itself no small act of heroism. It was delivered on 28 January 1919 in Munich, at a time of political crisis. The First World War had ended unexpectedly the previous November, not with a surrender but, inconclusively, with an armistice. There was huge conflict between nationalists, who wished to continue the fighting, and pacifists, who wished to end it. The question of Germany’s responsibility for starting the war was bitterly contested and violence frequently spilled out onto the streets. The Kingdom of Bavaria had been forcibly overthrown the previous November; just two weeks before the lecture, the radical Communists Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg had been executed after an abortive uprising; a month later, the Bavarian prime minister, Kurt Eisner, was assassinated.