The Dreyfus Affair

Douglas Johnson recounts the life of the infamous French army captain.

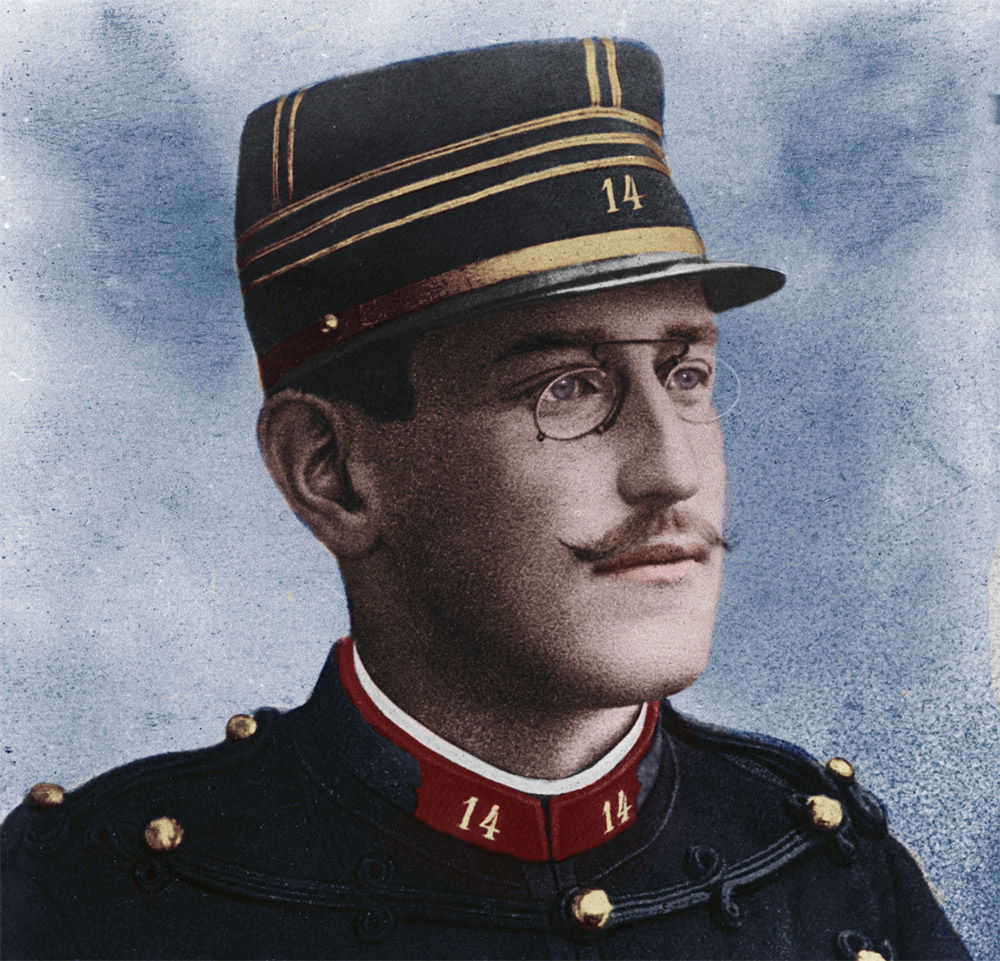

Alfred Dreyfus died in Paris on the evening of July 12th, 1935, aged seventy-four. He died surrounded by his family (his doctor, Pierre-Paul Levy, was his son-in-law) in his comfortable dwelling place in the 17th arrondissement. He died as he would have wished to live, peacefully, like a respectable bourgeois citizen.

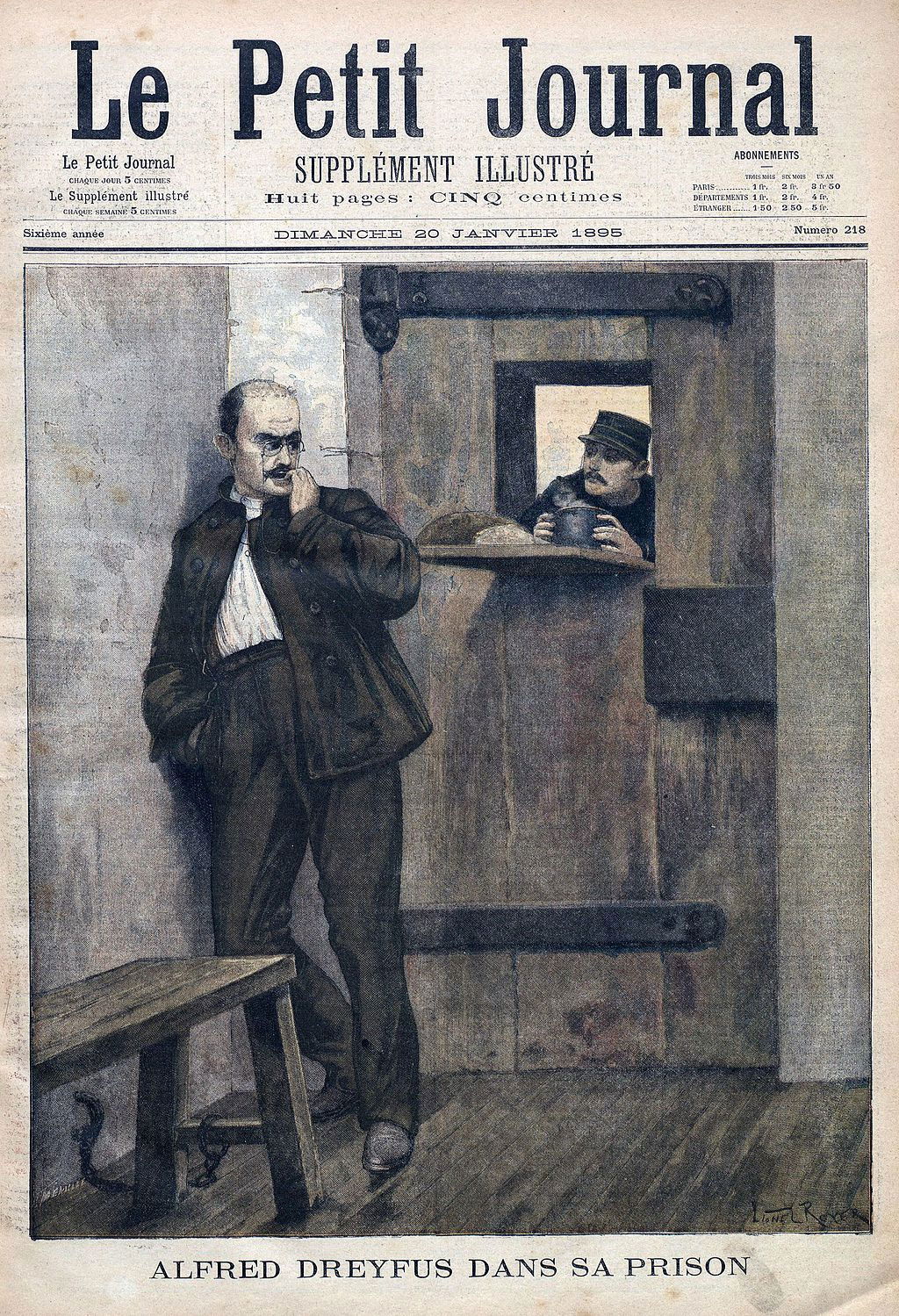

To say that Alfred Dreyfus was unfortunate would be the unacceptable phrase of understatement. Everyone knows that he was unjustly condemned for treason. Everyone knows too that the simple fact that he was Jewish was in itself enough to convince many, both in 1894 and now, that he must have been guilty. But his misfortune did not end with the agonies of exile on Devil's Island. They also involved hi friends and supporters.

It is often said that the hero of a cause célèbre is never a real hero, and rarely an attractive or likeable man. Dreyfus is invariably given as the best example of this. Some of the things said about Dreyfus have been repeated so many times that they have been accepted as established truths. Thus it has been said that had Dreyfus not been involved in the controversy, he would never have been a Dreyfusard. He would have been among the army officers saying that there should never be a re-trial and that one must not question military authority. One of Dreyfus' most ardent supporters said, 'we were prepared to die for Dreyfus. But Dreyfus wasn't'. And Clemenceau, who had published Zola's famous article J'Accuse which was the turning-point of the affaire, was dismissive about Dreyfus the man, saying that he looked like a pencil salesman.

There are many anecdotes which cannot be verified. Thus it is said that when Dreyfus learned that some unknown man had been arrested on suspicion of committing a crime, and it was pointed out that no one knew what was the evidence against him, then it was Dreyfus, of all people, who said 'There's never smoke without fire'. Sometimes when longstanding anecdotes are investigated they are found to be false. Thus we were told, apparently on good authority, that Dreyfus refused to intervene on behalf of the condemned anarchists Saccho and Vanzetti, whose case had frequently been compared to Dreyfus'. But it has been shown, from the New York World of 1927, that in fact Dreyfus did join the appeal against their execution. This revelation however has done little to save him from being badly thought of by those who passionately believed, and believe, in his innocence.

It is, of course, difficult to know exactly what a man was like. But there is no reason why one should not pay greater attention to the feelings of the family that loved him dearly rather than to the reactions of those who only knew him slightly or who only knew him in the very particular circumstances of his trials. One is therefore led to consider other explanations.

The first is the fact that having again been found guilty at his second court-martial, Dreyfus accepted a Presidential pardon rather than continue the fight. There were those among his supporters who never forgave him for that. They wanted to go on, from trial to trial, from appeal to appeal, until the essential falseness of the army's case against him would be plain for everyone to see and the army would be discredited. But Dreyfus was a sick man, and there were serious doubts whether or not he could stand further strain. It is revealing that some of those who had fought so hard for him were not so concerned about his health. But there was another element. Undoubtedly the Dreyfus family came under pressure to accept the pardon, and the pressure was apparently exercised by two groups of people. The one was composed of Republicans. The other of Jews. Both felt that they stood to lose by further controversy and confrontation. Whether one was the Prime Minister or Rothschild, one wanted the Dreyfus affair to end, and to go away. Many of the Dreyfusards could not understand this, or did not wish to understand this.

Those who supported Dreyfus expected him to behave in a certain way. They had, after all, worked hard and devotedly, on his behalf. Some of them had gone through emotional traumas and professional humiliations because they had had the courage to identify themselves with him. Some had made considerable sacrifices. Why then, they asked, could not the Dreyfus who was brought back from Devil's Island to France be more emotional, more demonstrative? Why did he not denounce the officers who were his enemies? Why did he not have a rhetoric which equalled their own?

Dreyfus rarely, if ever, spoke of himself as a Jew and he never protected that the injustice from which he suffered was because he was Jewish. In his autobiography he reveals nothing of himself and largely confines himself to quoting from letters which are, inevitably, repetitious. When the affaire was all over, he sought only privacy and silence. And therefore he was a disappointment.

In a cause célèbre everyone plays a role. And the central figure is expected to play a role. There were Dreyfusards who believed that they owned Dreyfus, that they had acquired rights over him. But they had not understood the first thing about him. That he was obstinate. How could he have survived if he had not been obstinate? And this obstinacy stayed with him, whether on Devil’s Island or by his fireside arranging his stamp collection.

'I was only an artillery officer whom a tragic mistake prevented from pursuing his career', he told a friend. He refused to be a symbol or a hero. He refused to be anything but himself. And perhaps it is this final determination and obstinacy which was the finest thing about him and about the affaire.