Port Arthur Revisited

Richard Connaughton on the need to re-evaluate an over-looked conflict of the early 20th century.

There are few wars so thoroughly documented, but about which so little is known, as the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War. It was far more important than is commonly imagined, prefiguring much of the military history of the twentieth century. Yet awareness is slowly growing of the context of this war, which took place at a time of international political change and at a moment when the nature of war was undergoing fundamental revolution. The forthcoming centenary of this conflict will bring new analysis, not least because of China's changing attitude to the war, which took place during her 'period of humiliation'

In 1988, when I first wrote a history of the war, the doors into Manchuria were still closed. A recent change of attitude within the Chinese government, however, has stimulated a desire to learn of this period of embarrassment that was ignored for so long. I have had the opportunity to visit the region, and being there matters.

When walking over these battlefields, the imagination runs riot envisaging the unremitting slaughter among the Russians and Japanese in battles which presaged the nature of the First World War. There was a mass of Western military observers and a large press corps which witnessed the effects and influence of logistics, pounding artillery, trench networks, mining, barbed wire and machine guns. Tragically, though, almost no lessons were learned. This was partly due to ignorance and partly down to a desire to preserve traditional interests – the cavalry, for example, was shown to be largely redundant. None of these Western observers, watching the incompetence of the Russians and the fanaticism of the Japanese, could relate what they saw to their own conflict scenarios. Arguably, the Russo-Japanese War had a greater impact upon the Second rather than the First World War.

It was a war fought by Russia and Japan for the domination of Korea and Manchuria, territory clearly owned by neither of the combatant states. Tsar Nicholas II did not want war with Japan. But some within his inner circle had commercial interests in the region and persuaded him that Japan would not dare take on Russia; if they did, a short victorious war would unite the nation and stem the rumbles of discontent.

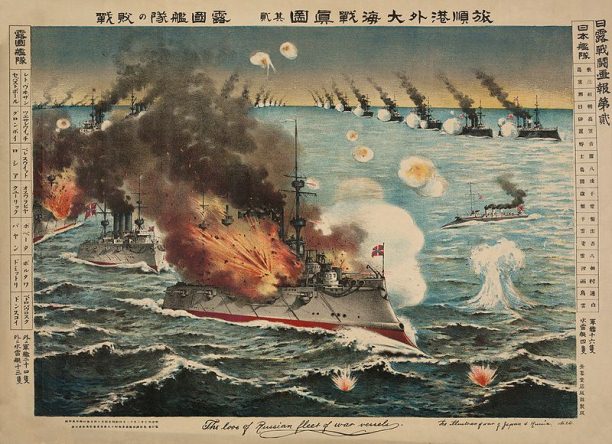

During the pre-war negotiations, the Russians stonewalled, refusing to take Japan seriously. The Japanese response during the night February 8th–9th, 1904, was to launch simultaneous attacks on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur (Lushun) and Chemulpo, the port of Seoul, Korea. As the war ended in 1905, the young Douglas MacArthur came here as aide-de-camp to his father General Arthur MacArthur, who had been sent by his government to measure the strength of the Japanese army and its methods in warfare. Under its better-known modern name of Inchon, Chemulpo was to be the site of Douglas MacArthur’s landing in the Korean War in September 1950. Meanwhile, on February 10th, 1904, Japan declared war on Russia.

Russia went on to lose every naval and ground battle she contested. It was Theodore Roosevelt who stepped in as peace-broker and, during August and September 1905, held the peace conference in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. As early as January 1905, Roosevelt had written that if Japan ‘tries to gain from her victory in the Russo-Japanese War more than she ought to have, she will array against her all the great powers, and however determined she may be she cannot successfully face an allied world.’ The Tsar refused to pay any indemnity and Japan, already finding difficulty paying high rates of interest on her war loans, was persuaded to concede. So, having in effect won the war, Japan emerged with the Russian lease on the Liaotung Peninsula and just half of frozen Sakhalin island to show for her troubles. The New York Times expressed incredulity: ‘A nation hopelessly beaten in every battle of the war, one army captured and the other overwhelmingly routed, with a navy swept from the seas, dictated her own terms to the victory’.

Japan erupted in protest, turning her fury upon the United States and the President for denying her her just reward. In letting Russia off the hook, the Portsmouth Conference set in train the suspicion and fatal rivalry between Japan and the United States in the Pacific that culminated in the attack on Pearl Harbor. Indeed, the carrier Akagi which led the attack on Hawaii in 1941 flew the same battle flag as was flown on Admiral Togo’s flagship Mikasa at the time of the pre-emptive strike on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur in 1904.

The battlefields of Manchuria have all been affected by a century of development and population growth. The exception is Port Arthur, which as a battlefield is complete to a degree that Sevastopol, for example, is not. Fort Sungshu and Golden Hill remain out of bounds but over 95 per cent of the Port Arthur battlefield is theoretically accessible.

Individual visits may not be simple to arrange, but it would not be impracticable to run a guided tour of this immensely significant battlefield still awaiting proper discovery. It is almost certain that by 2004, if not before, the Chinese authorities will be prepared to receive group visits from the West. To stand today upon 203 Metre Hill, looking around and through the harbour entrance into that open, fateful sea, generates the images of terrible conflict a hundred years past.