Halcyon Days, Indian Summers

This is a splendid and voluminous anthology, compiled from over 120 memoirs of a wide range of children of the Raj, including those of senior Indian Civil Service officers and army officers, businessmen, railwaymen, missionaries and Anglo-Indians. Mark Tully, himself one of the last Raj children and long-serving BBC man in Delhi, provides critical commentaries to both volumes.

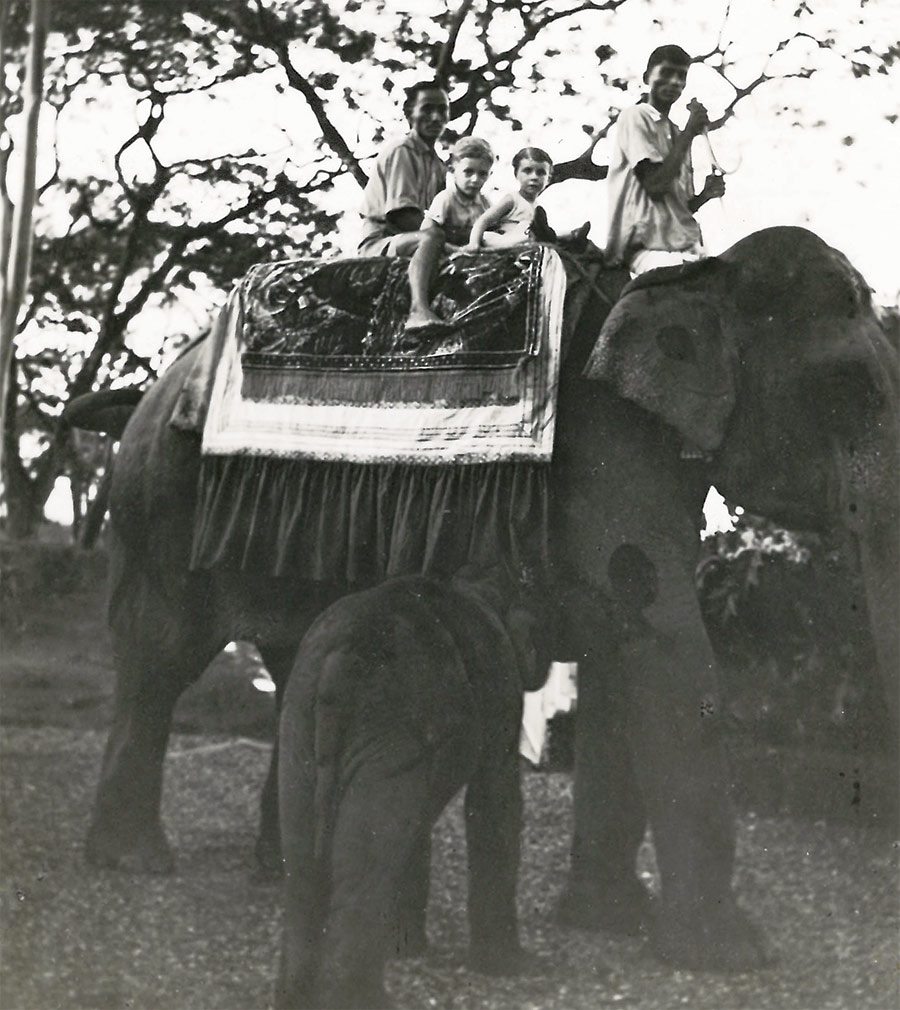

At first glance Raj children led idyllic childhoods. They lived in large houses with servants; they had an ayah (nanny) who let them roam through spacious gardens, invariably wearing their topees (pith helmets) as they rode their own ponies, accompanied by a syce (groom). When the weather become too hot, they escaped to the hill stations. Typical Raj houses, however, had no electricity, running water or flushing toilets and gardens concealed snakes and scorpions. In isolated places children alarmed their parents by playing with their servants’ children, acquiring an enviable fluency in local languages in the process. Then there was the question of education. Many were sent to boarding schools in the hills, such as in Darjeeling, which were modelled on British public schools and run on strict lines. Others were schooled in Britain and parents and children separated for years.

The outbreak of war in 1939 left hundreds of children stranded at schools in Britain. Many parents felt that they would be safer back with them, and, in 1940, in one convoy the P&O troopship Stratheden carried at least 200 children safely to India – to the delight of many. One child wrote: ‘I felt I was “home” again.’ Temporary schools were hurriedly created to accommodate them. When the students reached school leaving age, they began war work, the boys conscripted as officers into the British and Indian armies and the girls either running canteens for the troops, or as members of the Women’s Army Corps India. Romances blossomed, but grief soon followed as husbands were killed in Burma.

Indian nationalism barely affected the prewar generation, but later children were witnesses to the massacres which followed Partition in 1947. Despite such experiences, most children of the Raj were sad to leave India. They found Britain cold and grey, experienced rationing for the first time and some young wives even had to learn to cook. They frequently held nostalgia for the past, as one contributor wrote: ‘I was saddened to leave India. She had been good to me … It was a privilege to have been raised there.’

Last Children of the Raj: British Childhoods in India

Volume 1, 1919-1939; Volume 2, 1939-1950

Compiled by Laurence Fleming

Dexter Haven Publishing

477pp and 439pp £15 per volume

Richard J. Bingle was a Curator in the British Library’s Asian and African Collections.