Mesmerism In Victorian London

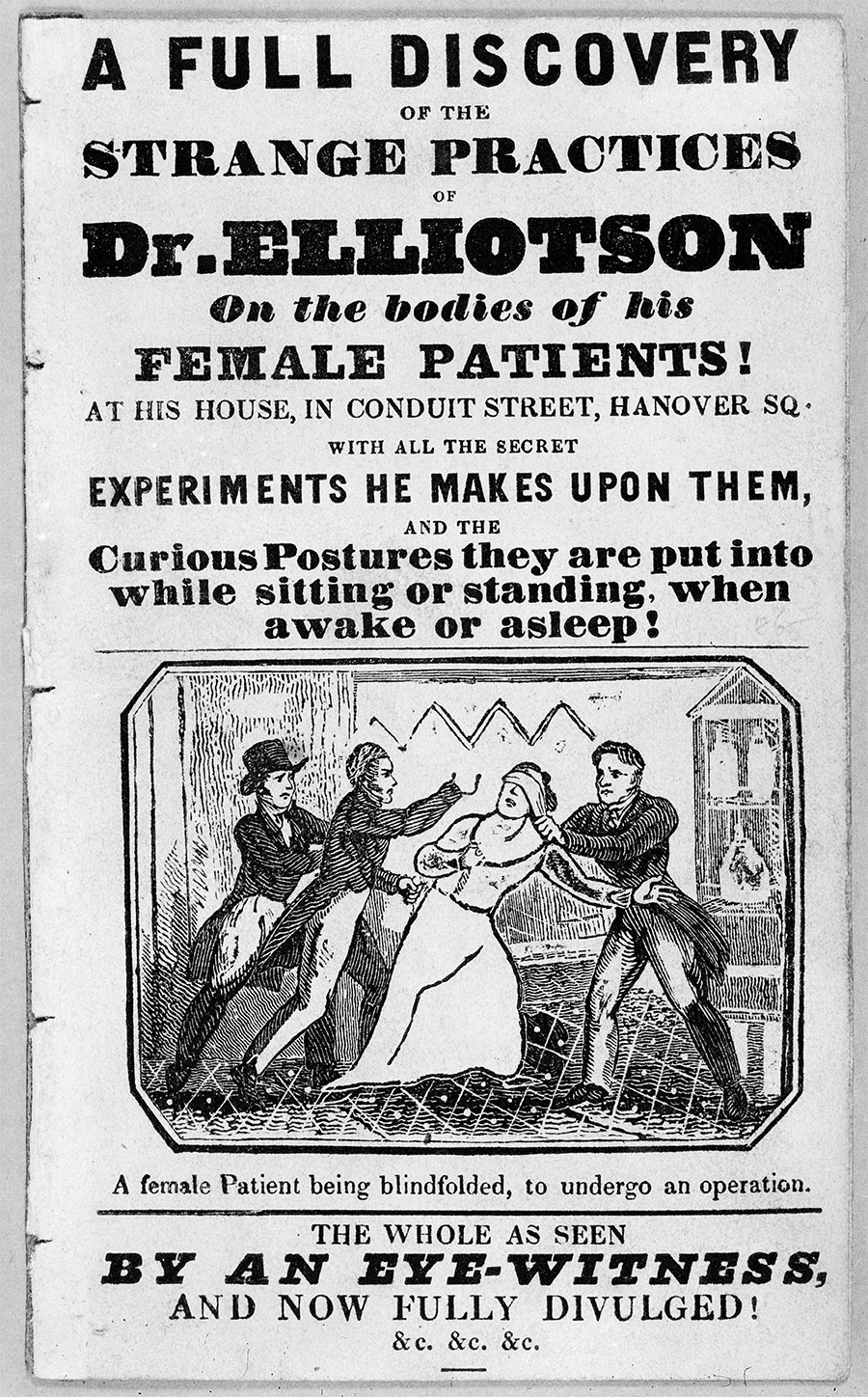

Mesmerism was a short-lived phenomenon, but its most celebrated British exponent, John Elliotson, attracted large crowds, which incensed his rivals.

Wendy Moore draws us into the illustrious world of Professor John Elliotson, while exposing the challenges between new and traditional medicine and the ensuing bitter competition between Victorian physicians.

Elliotson helped to found University College London, which opened in 1828, as well as the attached hospital a few years later. He quickly rose to fame among his peers, as he gained a reputation for giving entertaining lectures. He proved so popular that student numbers rose dramatically, pulling in money for the university and hospital. He was determined to expose quack medicine and malpractice and strove for excellence with a search for new medical techniques (although he continued with the useless practices of cupping, purging and blistering).

The arrival of the self-styled French baron Jules Denis Dupotet provided Elliotson with the new kind of medicine he was after – mesmerism. The practice had first been introduced to Paris in 1778 by Franz Anton Mesmer, a German physician who discovered that he could put people into a sleep-like trance, during which they obeyed commands, acted out strange behaviour and became insensitive to pain. Elliotson took up mesmerism and newspapers declared his public displays to be ‘real and unsophisticated, however inexplicable they may be on any known theory of disease’.

People flocked to watch Elliotson’s performances: the most notable was with a young domestic servant, Elizabeth Oakey, who suffered epileptic fits. Elliotson’s repertoire was to have her fall into a mesmeric trance, whereupon he would make her do all sorts of tricks for the audience. Once asleep, he would invite spectators to pinch her, pull her hair and stuff copious amounts of snuff up her nose to prove she could feel nothing, while the girl stayed completely motionless. Normally quite timid, under the influence but ‘awakened’, she would also mock her audience, sing songs, whistle and dance, while sometimes swearing at them. Elliotson later extended his experiments to others on the ward, including Elizabeth’s sister, Jane. Both young women gained celebrity status.

These experiments became the talk of the town and Elliotson’s rivals became incensed because of the numbers of people turning up, disturbing the ward rounds and the running of the hospital. The Oakey sisters were star turns but, eventually, their games went too far when they asserted that they could see through doors, diagnose patients and predict when a person would die, because they would see ‘Great Jackey’ sitting next to the doomed patient.

These antics caused a rift in the friendship between Elliotson and the founder of The Lancet, Thomas Wakley, who had initially been a supporter. Wakley became sceptical as he watched his friend perform increasingly outlandish experiments and felt he was being duped. After taking it upon himself to test the girls when Elliotson went on his annual holiday, Wakley quickly exposed them as frauds, declaring that ‘the effects which were said to arise from what had been denominated “animal magnetism”, constituted one of the completest delusions that the human mind ever entertained’.

Antagonism also developed between Elliotson and Robert Liston, surgeon at University College Hospital. Highly regarded, Liston was said to do the quickest amputation in town, although not always without problems; in his hurry to amputate a leg on one occasion, he also removed a patient’s left testicle. Both men were arrogant and bullish and, inevitably, rivalry intensified to the point of splitting the hospital into opposing sides.

Elliotson resigned from the hospital after he was prevented from treating his own patients. Despite a slight lull, his reputation again soared and soon he was leading the London Mesmeric Infirmary, which opened in 1850. Dramatic surgeries and recoveries were again reported.

Moore deftly uses a wonderful cache of information in University College Hospital’s own sources; the medical notes give detailed accounts of the trial cases undertaken. In this highly readable and entertaining account, she spotlights a largely forgotten figure in the history of medicine and opens up the world of petty rivalries.

The Mesmerists: The Society Doctor who held Victorian London Spellbound

Wendy Moore

Weidenfeld & Nicolson

320pp £18.99

Julie Peakman’s most recent book is Amatory Pleasures: Explorations in Eighteenth-Century Sexual Culture (Bloomsbury, 2016).