Mourning the Death of Prince Albert

Elisabeth Darby and Nicola Smith look at the impact of the death and funeral of Prince Albert, on both Queen Victoria and the nation.

John Hobshouse, Lord Broughton, woke up in his quite country retreat on Monday, December 16th, 1861 to discover 'The Papers in mourning - The Prince Consort died about 11 o'clock on Saturday night'. It was a very great shock, to Lord Broughton and to the nation as a whole. Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was only 42 and apparently had not been ill for long. Since his marriage to Queen Victoria in 1840, he had become the mainstay of his wife and family and a respected and imaginative adviser to Government, although the people had mistrusted him as a foreigner and never really warmed to him. Lord Broughton noted sadly that the Prince 'was an excellent man in all the relations of life - but his merits were not generally acknowledged' and he returned to the book he was currently reading. This was Thomas Carlyle's On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History , and the enormous success of this series of essays hints at one reason why the popular acclaim which had eluded the Prince Consort in life was heaped upon his memory.

Carlyle encouraged the cult of the individual, and promulgated the doctrine that 'Worship of a Hero is transcendent admiration of a Great Man ... No nobler feeling than this of admiration for one higher than himself dwells in the breast of man'. Queen Victoria had always been convinced of Prince Albert's qualities and she now buried herself amidst memorials of him - some simple and touching, some breathtakingly extravagant and some, to modern taste, macabre. She hoped that the people would worship him too. The fashion for extravagant mourning and the search for heroes got this cult off to a good start.

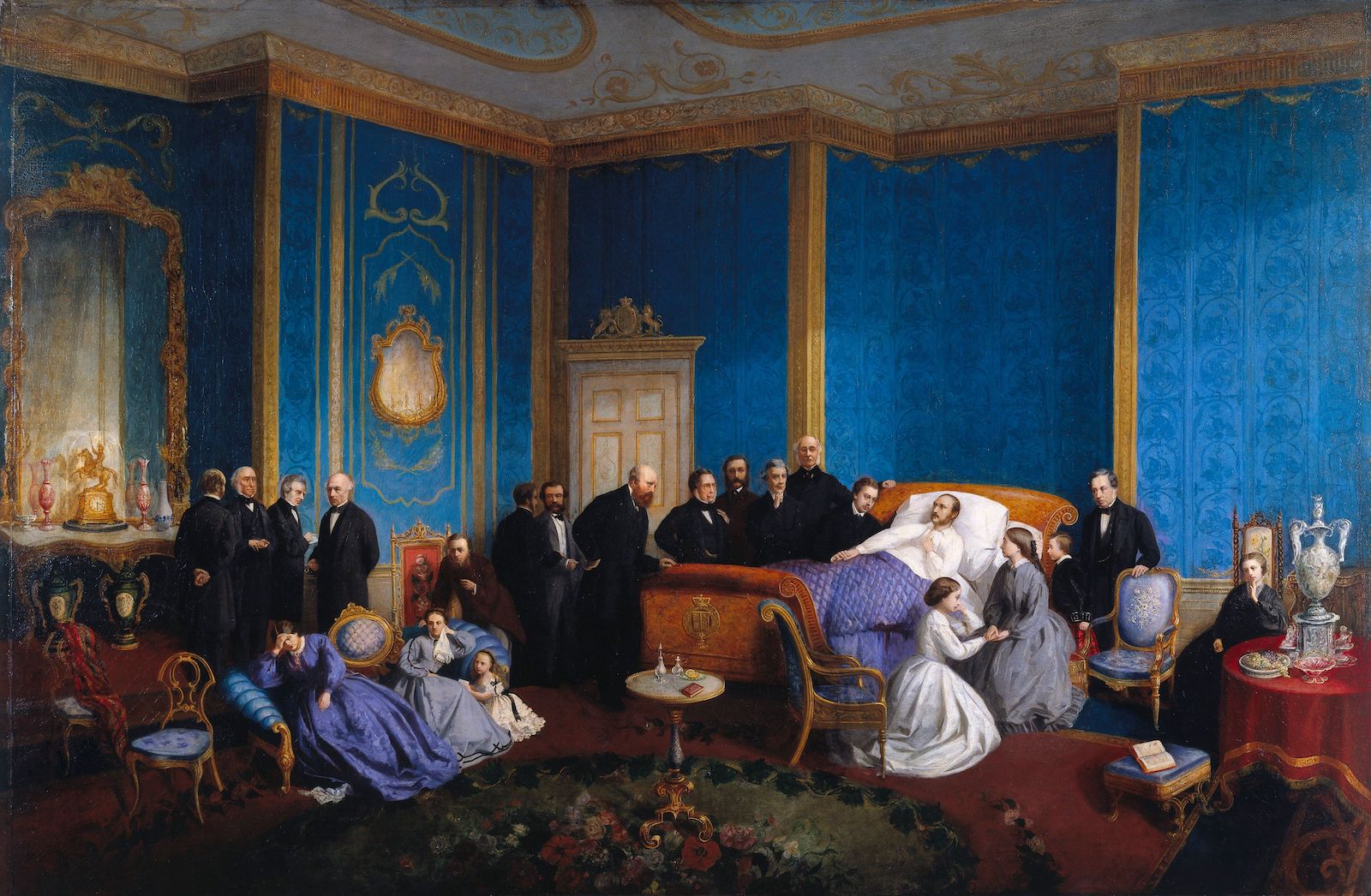

When Princess Alice called her mother back into the Blue Room at Windsor Castle where the Prince Consort lay suffering from typhoid fever on the evening of Saturday, December 14th, 1861, Queen Victoria knew that death was at hand. At 10.50 pm Prince Albert died. Years later, in 1872, the Queen could still vividly recall how:

Two or three long but perfectly gentle breaths were drawn, the hand clasping mine and... all , all , was over... I stood up, kissed his dear heavenly forehead & called out in a bitter and agonising cry 'Oh! my dear Darling!' and then dropped on my knees in mute, distracted despair, unable to utter a word or shed a tear! Ernest Leningen & Sir C. Phipps lifted me up, and Ernest led me out.

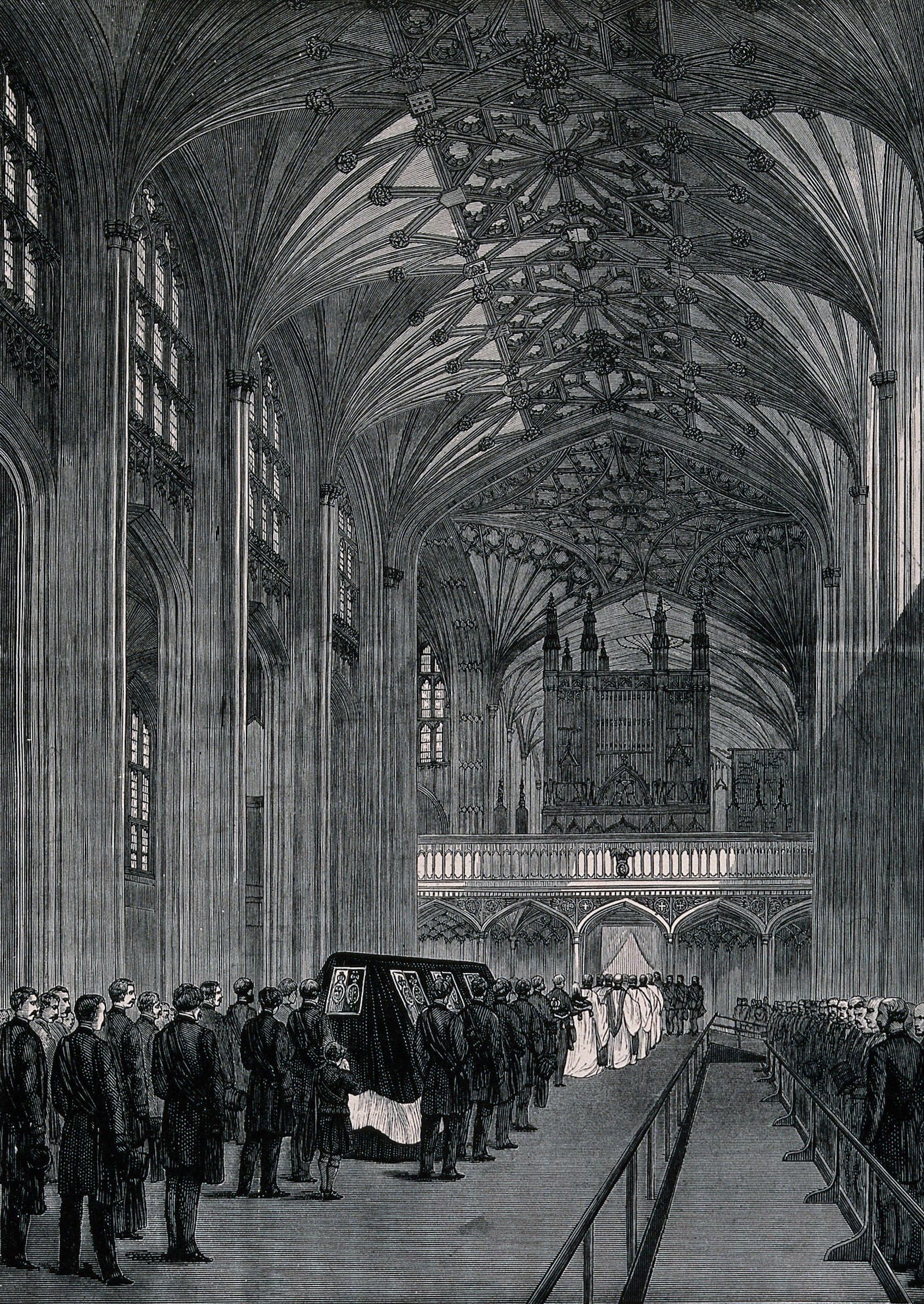

She returned to the death chamber twice the next day and wrote to her eldest daughter, the Crown Princess of Prussia, that Prince Albert appeared 'beautiful as marble – and the features so perfect, though grown very thin'. Although the body was not placed in the coffin until the 18th, Queen Victoria did not look upon it again, for, as she told her daughter, 'I felt I would rather (as I know He wished) keep the impression given of life and health than have this one sad though lovely image imprinted too strongly on my mind!' Prostrate with grief, the Queen retired to Osborne on the 19th, unable to face the ordeal of the funeral service which was conducted in St George's Chapel on the 23rd.

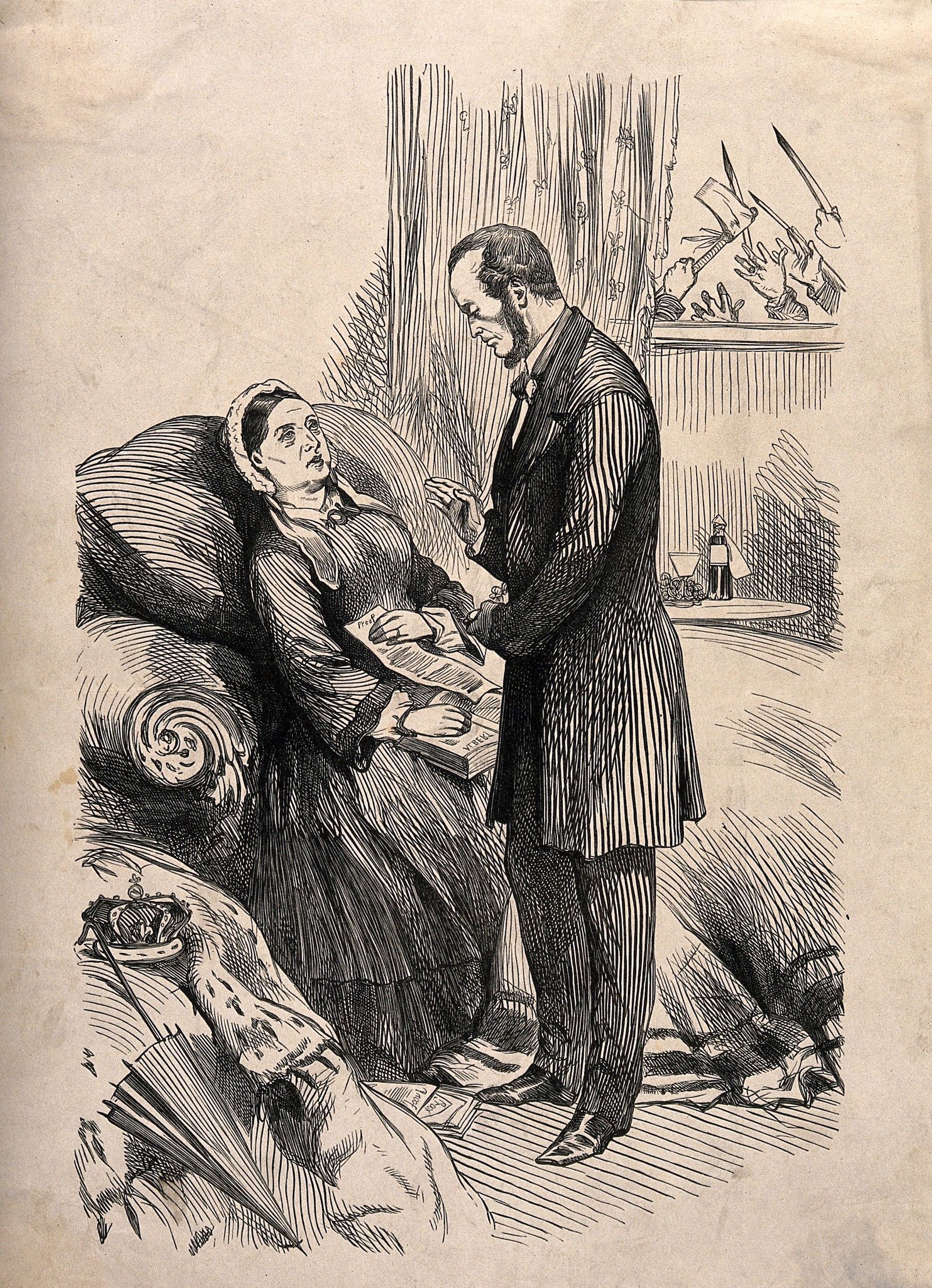

Queen Victoria had depended upon the Prince Consort in every way, from drafting her official letters and despatches, to approving her dresses and bonnets. Suddenly, her support was gone. In moments of extraordinary composure during the early days of her widowhood, fostered by a recollection of Prince Albert's advice at the time of her mother's death that she must control her feelings and not dwell on her sorrow, the Queen expressed her determination to carry out her duties to the country as he would have wished her to do. But these moments of calm resolution alternated with paroxysms of despair. Although she believed Prince Albert to have been 'too pure and too good for this world' and that 'His great soul is now only enjoying that for which it was worthy', it seemed at times that 'to live without him is really no life', and in these anguished moments, Queen Victoria's only wish was to 'follow him soon'. She was consoled, however, by the conviction that, still 'living, only invisible', her husband continued to watch over her, and that they would meet again in their 'eternal, real home’.

After the death of her mother, the Duchess of Kent, in March 1861, the Queen and Prince Albert had read together Reverend William Branks' Heaven our Home , the first edition of which was sold out within a week of its publication in 1861, and which eventually sold over 100,000 copies. The author was emphatic that friends would meet again in an 'eternal home of love , and recognise them, and speak with them in the language of heaven ', and that those already departed have a 'deep and glowing and unquenchable interest' in those still on earth. Prince Albert had accepted these views, and expressed to his wife his certainty that they would 'recognise each other and be together in eternity'. After his death the Queen compiled an Album Inconsolativum of letters of condolence, and of extracts from tracts concerning the future life and works of German and English poets. Of these, Alfred Tennyson's In Memoriam seems to have afforded her particular consolation, and large sections of the work were transcribed into the Album Inconsolativum . The Queen there altered words to make their meaning more applicable to her own situation: she substituted 'widow' for 'widower', and 'her' for 'his' in the lines 'Tears of a Widower', for example. She recorded in her diary for January 5th, 1862, that she was 'much soothed and pleased with Tennyson's In Memoriam , and that 'only those who have suffered as I do, can understand these beautiful poems'. The consolation afforded by Tennyson's In Memoriam was perhaps partly a result of Prince Albert's admiration for it, but also because of the belief it expresses in a future life. The Duke of Argyll informed Tennyson that the Queen found certain passages 'specially soothing' because they echoed her strong belief 'in the Life presence of the Dead', and it was for this reason too that he advised the Poet Laureate not to use the word 'late' in relation to the Prince Consort when he was invited to Osborne in April 1862.

Reflecting her determination to 'treat him as living', Queen Victoria ordered that the Prince's private rooms at Windsor, Balmoral and Osborne were to be retained just as he had left them, and kept up as if he were still to use them. When Lord Clarendon visited the Queen at Osborne in March 1862:

She talked upon all sorts of subjects as usual and referred to the sayings and doings of the Prince as if he was in the next room. It was difficult to believe that he was not, but in his own room where she received me everything was set out on his table and the pen and his blotting-book, his handkerchief on the sofa, his watch going, fresh flowers in the glass, etc., as I had always been accustomed to see them, and as if he might have come in at any moment.

Every night Prince Albert's clothes were laid out, and a jug of hot water and clean towels were put in his dressing room, as though ready for his use. Nevertheless, the truth was revealed by the coloured photograph of his corpse which hung over his side of the bed in each of the royal residences.

Queen Victoria also kept by her bedside casts of the Prince's face and hands which had been taken by the sculptor William Theed. Though she could not bring herself to look at the death mask (knowing that Prince Albert had found such things distasteful) the hands comforted her, and in moments of despair she clung to them as she might have done in life. The numerous painted and sculpted portraits of the dead Prince which Queen Victoria commissioned also provided her with solace, and served as the most vivid reinforcements to her belief that her husband was still watching over her.

During his lifetime, Queen Victoria had been guided by Prince Albert in artistic matters. After his death, she had to rely on what she knew to have been his taste and choice of artists, and on the judgement of close relatives. Of the latter only the Prince of Wales was excluded. The previous autumn he had indulged in an indiscreet affair with an actress, and the Queen believed that worry over his son's 'fall' had contributed to the Prince Consort's death. In her distress, she could hardly bear Bertie's presence, and he was accordingly dispatched on a continental tour early in February 1862. Though he contributed to the financing of the Royal Mausoleum, the Prince of Wales did not assist his mother with her other memorial schemes. In the planning and execution of these, Queen Victoria relied especially on her two eldest daughters, and in particular on the Crown Princess of Prussia, her father's favourite, though she had been unable to rejoin her mother in England immediately for fear the strain might endanger her pregnancy.

The Crown Princess had spent the day of her father's funeral in Berlin sitting 'with all dear, darling, blessed Papa's photographs on my knees, devouring them with my eyes, kissing them and feeling as if my heart would break'. Queen Victoria sent her other 'dear precious relics and hair', and later a drawing of her father's body by E.H. Corbould 'in a case with a key'. Early in January 1862 she sent copies of the casts of Prince Albert's hands to the Crown Princess who described the anguish of unpacking them:

It was a dreadful moment when I first saw them I thought my heart would break – I felt quite faint! They were the 1st thing that brought home to me the dreadful reality those dear hands I was so happy to kiss so happy to hold the rings I knew so well – all so like – and yet thin as I had never known him. Oh how dreadful to see them only in the cold plaster & to think I shall never kiss them again, it was an agony which I cannot describe!

The Queen had, of course, intended to soothe rather than distress her daughter, and the Crown Princess later wrote that the casts 'are really a comfort to me! ' She also derived consolation from assisting her mother with ideas for memorial schemes. Queen Victoria had written to her on December 18th, 1861, 'I do hope you will come in two or three weeks; it will be such a blessing then. I shall need your taste to help me in carrying out works to His memory which I shall want His aid to render at all worthy of Him! You know His taste. You have inherited it'. The Crown Princess advised her mother on the design of the Royal Mausoleum, the Albert Memorial Chapel, and on the statues and busts which played such a prominent role in Queen Victoria's commemoration of her husband.

Ignoring the Prince Consort's request that should he die before her, she would not 'raise even a single marble image' to his name, the Queen proceeded immediately after his death to commission two full-size statues, a group, and several busts and statuettes of her beloved husband for her residences, and as gifts for members of her family and faithful servants. In addition, photographs and several of the memorial paintings Queen Victoria commissioned, show her alone, or with her children, grouped around posthumous busts of the Prince Consort.

William Theed, a sculptor who had been respected by Prince Albert, was chosen to execute most of this memorial sculpture. The Queen retired to Osborne on December 19th, 1861, and it was here, within two weeks of the Prince Consort's death that Theed began work on the first posthumous bust. She told the Crown Princess on January 27th, 1862, that it was 'life itself’. The completed marble bust, showing the Prince Consort with bare shoulders, was placed between the two beds in the Blue Room at Windsor Castle where he had died, and which the Queen wanted to 'dedicate... to him not as a Sterbe-Zimmer – but as a living beautiful monument'. The appearance of the room was recorded in photographs, and on the first anniversary of the Prince's death, Theed's bust was moved and placed on one of the beds where, surrounded by flowers, it formed the focus of the three memorial services which were conducted there that day.

A second bust by Theed, also completed in 1862, shows Prince Albert with drapery over his left shoulder held by a buckle carrying a portrait of the young Queen Victoria. The pedestal for this, ornamented with cherubs' heads and flowers, was designed by Princess Alice, and took Theed twelve months to finish 'owing to the minuteness of execution'. In February 1864 it was placed in the entrance hall at Osborne on a 'memorial altar' of coloured marble with bronze ormolu wreaths.

Both busts appear, garlanded with wreaths, in photographs taken in 1862 of the Queen with sons and daughters, or the children on their own. The draped bust is also to be seen in the background of Albert Graefie's portrait of Queen Victoria as a widow commissioned in 1863, and completed the following year, and in the unfinished memorial picture of her with some of her children which the Scottish painter, Joseph Noel Paton, was summoned to Windsor in February 1863 to execute.

William Theed also executed statues of Prince Albert for the Queen, the first of which was destined for Balmoral Castle, and appropriately shows him in Highland dress, with a deerhound by his side. The pose of this figure seems to derive from John Philip's portrait of the Prince Consort commissioned in 1858 by Aberdeen Town Council, the oil sketch for which hangs at Balmoral Castle. The Queen probably asked Theed to model his figure on this portrait because, as she told the Crown Princess, Philip was 'our greatest painter', and 'darling Papa had such an admiration for him'.

While staying at Osborne, Queen Victoria recorded in her journal on January 1st, 1862, that she 'went down to see the sketch for a statue of my beloved Albert in Highland dress, which promises to be good'. In May 1862 Theed travelled to Balmoral to discuss sites for the figure, and the following August, the full-size plaster model was despatched to the Castle to be tried in different positions. Eventually a place at the foot of the staircase was decided upon, and when, after two hours hard work, the cast was finally erected, Queen Victoria observed that it 'looked most beautiful & so life like'.

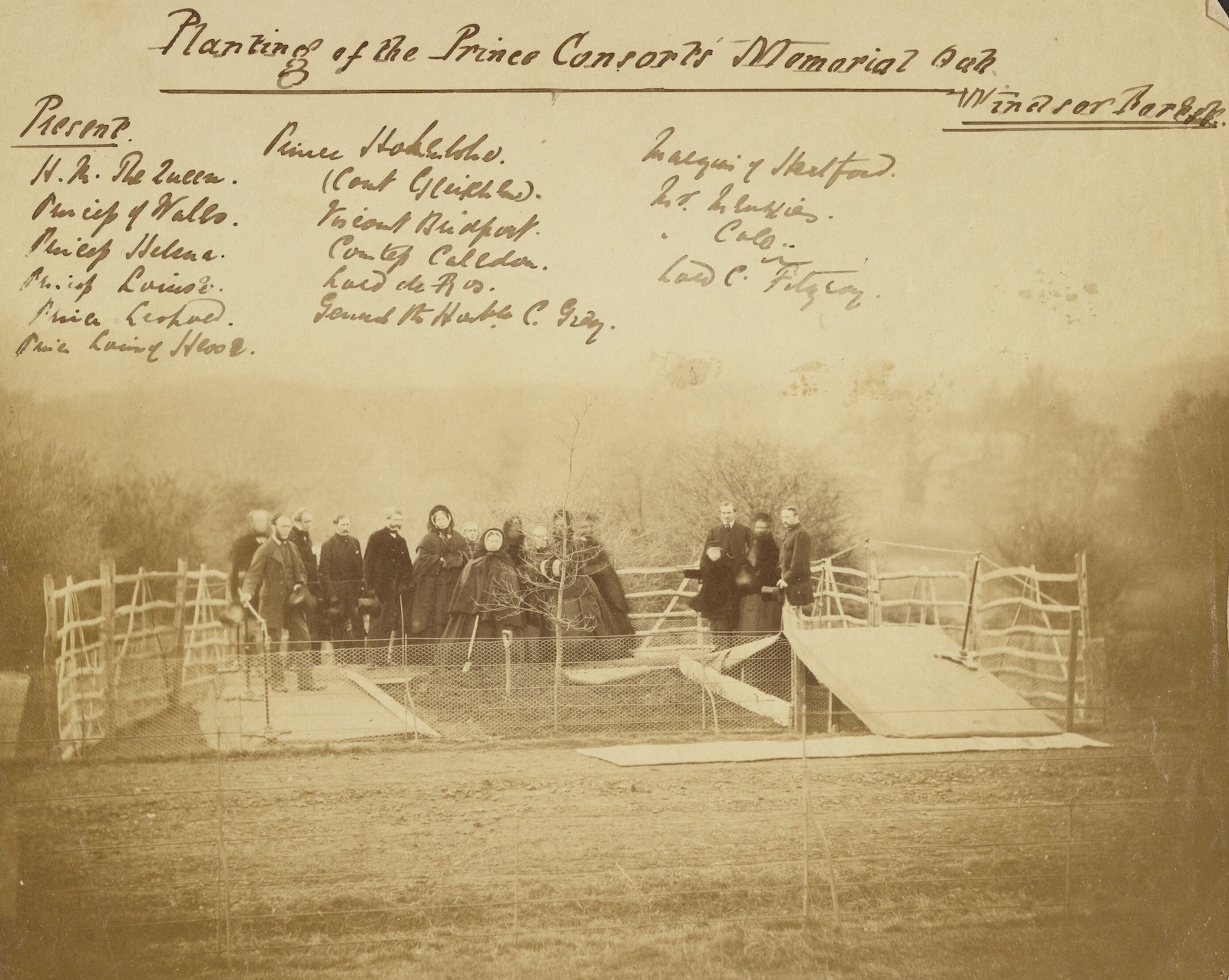

On August 26th (Prince Albert's birthday), the royal children 'placed wreaths of heather on the beloved R beautiful statue'. The cast remained at Balmoral until the Queen returned to London when it was dispatched to Theed's studio for execution in marble. The completed statue – 'a wonderful likeness' – was unveiled at Balmoral at a ceremony attended by the Queen, members of the royal family and household on October 17th, 1863. The inscription on the pedestal – 'His life sprang from a deep inner sympathy with God's Will, and therefore with all that is true, and beautiful and right' – was a phrase used by Norman Macleod in a letter to the Queen, dated December 28th, 1861, which she transcribed into her Album Inconsolativum .

Soon after the unveiling, Queen Victoria decided to present a bronze replica of the statue to the tenentry at Balmoral. In June 1864, a painted plaster cast was tried out on the chosen site in the castle grounds, but on inspecting this, the Queen decided it was too small, and ordered a colossal statue instead which would be 'seen from everywhere'. This was cast in bronze by the firm of Elkington's that autumn, erected on a base of roughly-hewn stone, and unveiled on October 15th, 1867.

Theed's most elaborate piece of memorial sculpture for the Queen was the life-size group showing Prince Albert and herself in Anglo-Saxon dress, which was also known as The Parting . The sculptor was working on the clay model when the Queen and Princess Alice visited his studio in March M63 to 'superintend the head' of the statue of Prince Albert. After another visit in March 1865, she noted that 'the beautiful touching group of us together' was far advanced in marble. The completed work was unveiled in a corridor in Windsor Castle on May 20th, 1867. In submitting his bill for the group (which had greatly exceeded his original estimate), Theed observed that the work had taken him five years to complete, the difficulties of the execution being exacerbated by 'the position of the figures, which rendered the necessary undercuttings, most laborious, but especially in the Statue of His Royal Highness'.

The idea of depicting Prince Albert and Queen Victoria in Anglo-Saxon dress seems to have been suggested by the Crown Princess. Subjects drawn from Anglo-Saxon history had been popular with artists since the 1760s', but the number of statues and paintings devoted to such themes reached a peak in the middle years of the nineteenth century. Theed's group, while undoubtedly influenced by this artistic vogue, does not represent Prince Albert and Queen Victoria as particular characters from Anglo-Saxon history. Neither does it commemorate any entertainment at which they wore Anglo-Saxon costume: the royal couple had not chosen this period as the theme for any of the fancy-dress balls for which they showed such enthusiasm. Rather, the group symbolises the ties between the German and English peoples from their origin in the Anglo-Saxon period to the nineteenth century, and Prince Albert's marriage to Queen Victoria. The allusion would have had special meaning also for the Princess Victoria whose own union with the Crown Prince of Prussia had been conceived by the Prince Consort partly as a means of strengthening the bonds between England and Germany.

The group was given a Christian emphasis by the inscription, 'Allured to brighter worlds, and led the way', taken from Oliver Goldsmith's The Deserted Village . These lines occur in the description of the parson of the village of Auburn whose life was devoted to bringing himself and his flock nearer to God.

The Queen gave sculptures of Prince Albert to members of her family. She sent a bronze bust by Marochetti to the Crown Princess for her son William in January 1862; and the baptism of the Prince of Wales's son, Prince Albert Victor, on March 10th, 1864, provided the occasion for her to commission a statuette for the new baby 'in Memory of Albert, his beloved Grandfather'. A second version was presented by the Queen to another godson, Prince Christian Victor of Schleswig-Holstein, son of Princess Helena, for his christening on May 2lst, 1867 The original was designed by E.H. Corbould, instructor in history painting to the royal family since 1851, and relates to a picture he had just completed for the Queen. Both works take as their theme Prince Albert as a Christian Knight, and are inscribed with variations of the Biblical text from 2 Timothy Chapter 4, 'I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith'.

Corbould's painting shows the Prince Consort clad in medieval armour, and is based on Robert Thorburn's miniature executed in 1844. This was the Queen's favourite portrait of her husband and after his death became so precious to her (perhaps because she observed that his features during his last illness bore an extraordinary likeness to it) that she hardly let it out of her sight. It was only with the greatest reluctance, and on the condition that 'the glass was not removed', that she lent it to Theodore Martin to be copied for the frontispiece of the first volume of his biography of the Prince Consort. Thorburn's painting was, however, a fancy dress piece, and Corbould transmuted this image into a pious one by making it the central panel of a trompe l'oeil 'triptych', by surrounding it with Biblical scenes, and by depicting the Prince as a Christian Knight in the act of sheathing his sword, his good fight fought. The painting was completed early in 1864, and almost immediately Corbould was engaged to design the christening present for Prince Albert Victor.

The statuette of the Prince Consort is a re-working of the figure in Corbould's picture, but it was modelled by Theed who copied the head from his own bust of Prince Albert. The pedestal is decorated with figures representing Faith, Hope and Glory, also modelled by Theed; with verses composed by Mrs Prothero, wife of the rector of Whippingham; and with coats of arms, roses, lilies and other enrichments in enamel. The imagery and verses of the front panel – including a white lily bent over a broken rose the. Inscription 'Frogmore' – record Queen Victoria's great loss, and her joy at the birth of her grandson. The other two panels contain verses exhorting the newborn prince to emulate the virtues and exemplary life of the illustrious grandfather that he never saw, so that he too might earn the rewards of heaven – symbolised by the ebony band set with silver stars around the base. The christening present, which Queen Victoria described as 'most beautiful '; was given to Prince Albert Victor at Christmas 1865: the theme was to be taken up again by Henri de Triqueti in the effigy of the Prince Consort in the Albert Memorial Chapel.

Queen Victoria was very concerned that a written record should be compiled to perpetuate the memory of her husband and their life together. In May 1863 she asked the Crown Princess to assist her by writing a description of a typical New Year's Day:

beginning with you children standing in our room waiting for us with drawings and wishes; Grandmama at breakfast, then you children performing something or a tableau, and your playing and reciting and in the evening generally a concert or performance with orchestra – then our wedding day the same... and later my birthday perhaps... and put down any picture of darling Papa's manner.

These observations were intended by the Queen for a book which her children and grandchildren would inherit, and for General Grey's life of the Prince Consort which he was compiling under the Queen's direction. This latter work was also originally intended for private circulation among members of the family only, but for fear of a copy being 'surreptitiously obtained and published, possibly in a garbled form', it was decided to make the work publicly available. Other commitments prevented Grey from undertaking a complete biography, and his account, The Early Years of His Royal Highness the Prince Consort , which was published in 1867, covers Prince Albert's life up to the first year of his marriage.

Queen Victoria's own Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands , from 1848 to 1861 was likewise originally intended for private circulation among her family and friends, but in order to forestall 'incorrect representations of its contents' appearing in the press, this volume was also published, in 1868. Illustrated with Queen Victoria's own sketches, 20,000 copies were sold immediately, and the work quickly went into several editions.

The only literary work which Queen Victoria commissioned for publication immediately after her husband's death was a volume of his speeches and addresses, compiled by Sir Arthur Helps who later assisted her with Leaves from the Journal . This appeared in 1862 and was immediately translated into other languages. In writing the prefatory sketch of Prince Albert's character, Helps was directed by Queen Victoria, and he noted that some parts were rewritten 'six or seven times under the Queen's own supervision'.

These early biographies of the Prince Consort by Martin, Helps and Grey, written at the Queen's command and under her close scrutiny, were intended to convey to the public the nature and extent of her loss, and perhaps reflect too keenly her view of her husband as 'an Ideal and a type of the heavenliest of Mortals'. After his death, Prince Albert assumed the status of a saint in her eyes. She adopted capital letters for pronouns referring to him as a mark of pious respect; she described the placing of the body in the Royal Mausoleum as its 'translation', and she kept anniversaries connected with his death and burial as 'holy days'. A print after Thorburn's portrait of Prince Albert hanging over her grandson's cradle looked to her like that of 'a patron saint', while in the upper part of E.H. Corbould's memorial 'triptych' (itself a devotional form), he is depicted exchanging his earthly crown for a halo. The casts of his hands and face, and locks of his hair were all treated as 'sacred' relics, and the places which he had inhabited became hallowed ground to be marked with monuments or preserved as shrines.

Queen Victoria's worship of the Prince, her desire to preserve relics associated with him and their life together, and to fill her residences with his image, was an excessive manifestation of the nineteenth-century obsession with mourning. Although extravagant ritual displays of grief were customary at this date, these were generally of limited duration, and it was not frowned upon for a widowed partner to remarry quite shortly after his or her bereavement. There were early rumours that the Queen would 'get over her loss and perhaps marry again' – but for her this would have been unthinkable. No one could replace Prince Albert for whom Queen Victoria's personal mourning never ceased, and for whom she ordered that official mourning should be 'for the longest term in modern times'.

The Queen was, as Lord Clarendon remarked, 'very watchful about what people do and how the mourning is observed. She sent back the other day all the papers she had to sign because the black margin was not sufficiently broad'. She herself always used black-edged writing paper thereafter, and wore widow's weeds (and often her widow's cap – the 'sad cap' as Princess Beatrice called it) until the last days of her life. Although posthumous busts and paintings, and jewellery incorporating portraits of the deceased, were common features of Victorian mourning, the extent to which the Queen bedecked her person and crammed her residences with memorial images of her husband far exceeded normal nineteenth-century practice. Mourning became 'a sort of religion' for her – and remained one. Queen Victoria's position, and her personal wealth, allowed her to indulge to the full her enthusiasm for mourning and monuments.