Back to the Dark Ages

The 'Dark Ages' is an outdated stereotype abandoned by historians years ago, which makes its use by English Heritage all the more disappointing.

To academic historians the Dark Ages are a thing of the past. And yet English Heritage, in their timeline of the Story of England from the prehistoric to the modern period, shows that, after the Romans left Britain, the nation fell into the ‘Dark Ages’ before resurfacing for two distinct Middle Ages, neatly chopping medieval England into pieces.

The term ‘Dark Ages’ found a foothold in the 17th and 18th centuries, with historians like Edward Gibbon writing about the ‘darkness’ of the period, and reached its peak in the mid-19th century as, with a fervent belief in the dawn of a modern age, a growing Empire needed to build a dark past from which to emerge. The Dark Ages cling to Victorian ideals.

As a concept it is steeped in intellectual and cultural superiority used to dismiss the early Middle Ages as a period of ‘intellectual darkness’ before the Renaissance. In fact, we know far more about late Anglo-Saxon England than we do about Roman Britain.

The phrase feeds into a romanticised view of the period: lost to the mists of time, savage and lawless. But that could not be further from the truth. We might not have the overwhelming wealth of materials of later periods but enough survives to see the extent of their intellectual and cultural development. Pre-Conquest England was not without law, culture and politics.

The Anglo-Saxons had an elaborate legal system, which was written down in law codes from the early seventh century, and these were often written in Old English, one of many intellectual innovations unique to Anglo-Saxon England. The law codes predate Magna Carta by 600 years and laid the groundwork for it. Yet it is Magna Carta that we now credit as the foundation of English law.

Certainly there was instability, as various powers fought among themselves and against interlopers, but it is out of this instability that the concept of a unified ‘English people’ and, later, ‘England’ was born.

Anglo-Saxon England was peopled with learned men and women, highly educated in Latin and English, who circulated and read Classical texts as well as composing their own, continuing the traditions they had inherited. There survives a large corpus of literature showing a deep understanding of the physical and the metaphysical and many productions showing great learning – take the writings of Bede, who is still regarded as the father of English history.

Charters show that laws, administration and learning were not just for an educated elite. Laypeople were involved in the ceremonies and had documents created for them: land grants, wills, dispute settlements (take, for example, the Fonthill Letter, which exerts considerable bureaucracy on the theft of a sword and some oxen). And the coinage across the period shows an elaborate and controlled economy. This was a well-managed society not given to lawlessness and chaos.

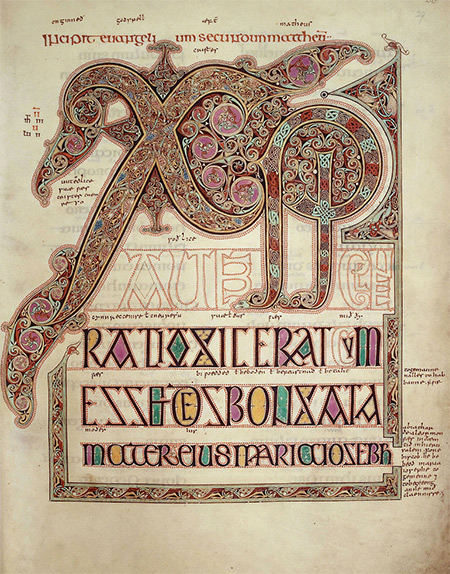

The Anglo-Saxons were also skilled artists. It is impossible to look at manuscripts like the Lindisfarne Gospels or the Benedictional of Æthelwold and conclude that this was a society living in intellectual darkness. They drew influence from Classical art and developed their own distinct artistic styles with as much skill and flair as later medieval artists. And we must not forget the breathtaking metal-, glass-, gold- and garnet-work of sites like Sutton Hoo and the Staffordshire Hoard, worn by warriors who would have sparkled in the sunlight. This was not just craft for necessity; they had the means and the ability to create objects of beauty for its own sake.

The Norman Conquest of 1066 saw the start of a closer political relationship with the Continent, but this was not the first time England had connected with Europe. Similarly, the end of Roman Britain did not mean Britain was suddenly isolated and fell back into savagery. These great feats of cultural production would not be possible had Anglo-Saxon England existed in isolation. They had trade routes stretching across the known world and were familiar with and able to buy spices, pigments and cloth from thousands of miles away (many manuscripts use a blue pigment made from lapis lazuli, brought from Afghanistan, for example).

From the end of the late sixth century and the beginning of the seventh, Anglo-Saxon England was a part of the Christian world. The English church was in close contact with Rome, with correspondence travelling back and forth; new bishops would be sent to Rome to collect the pallium; and King Alfred visited the city as a young boy. Later in life he collected around him a group of learned men influenced by the cultural life he encountered through contact with the Continent. English men in turn influenced the Frankish kingdoms under the Carolingians.

The Conquest is a useful boundary, but we must remember both that it is artificial and that it only applies to England. The Conquest may have marked the end of many things but it is certainly not the case that Anglo-Saxon England ceased to exist in 1066. This is a moment when England was both Anglo-Saxon and medieval: a stage of continuities and transition. Many important political, religious and cultural changes were underway but the Anglo-Saxons did not stop being Anglo-Saxons. As an artificial divide it also separates England’s story from its European contexts and puts it out of step with – and centuries behind – a world it was categorically in step with.

We should have moved past the image of a savage Dark Ages by now, certainly in national institutions which purport to authority and to provide public education, but that seems not to be the case.

I am not denying that the Anglo-Saxon period be considered as distinct from the later Middle Ages: culturally and politically they were different beasts, although continuities can and should be recognised. But to dismiss it as a 'Dark Age' is to ignore a rich and vibrant society, which saw the beginning of so many things we now think of as inherently English. Civilisation did not begin with the arrival of the light-bearing Normans.

With this timeline, English Heritage is holding on to a Ladybird book approach to history, in which a new country can emerge from darkness. It is denying history.

I am indebted to Charles West (@Pseudo_Isidore), Fern Riddell (@FernRiddell) and Robert Gallagher (@Hwaetspur) for their thoughts on this piece. #stopthedarkages

Read English Heritage's explanation as to why they used 'Dark Ages'

Kate Wiles is contributing editor at History Today.