Seeking Shelter in Victorian London

Homelessness was an acute problem in the 19th-century city.

When Penguin published The Buildings of England: London Except the Cities of London and Westminster, Pevsner's text referred to the Rowton Houses in Camden Town as 'still belonging to the slums'. This brought a threat of action against the publisher for defamation. Rowton Houses are now largely forgotten, but figure in the Homes of the Homeless exhibition at the Geffrye Museum.

When Penguin published The Buildings of England: London Except the Cities of London and Westminster, Pevsner's text referred to the Rowton Houses in Camden Town as 'still belonging to the slums'. This brought a threat of action against the publisher for defamation. Rowton Houses are now largely forgotten, but figure in the Homes of the Homeless exhibition at the Geffrye Museum.

Starting with life on the streets, the exhibition reveals that the homeless had to sleep during the day because the police moved them on at night. Homelessness became an acute problem in London as the drift from the country to the towns accelerated in the early 19th century. Itinerant workers, 'Navigators' or 'navvies', arrived in vast numbers to dig the canal network and to build the railway lines. Where were they to be housed? What would they eat? If a labourer lost his job, he and his family might be made homeless.

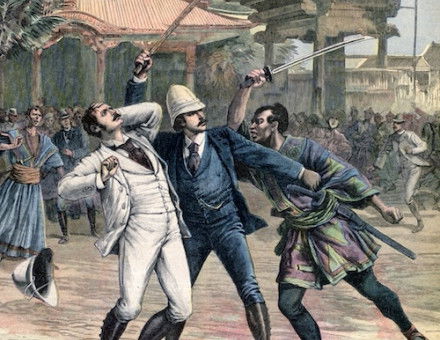

The rapid growth of slums, often in close proximity to wealthy areas, alarmed those of the middling class and motivated religious zealots. Faster, cheaper methods of graphic reproduction fed the consternation of the better-off. Magazines such as the Graphic, the Illustrated London News and the Sketch shocked their readers with pictures of poverty. Religious campaigners fuelled controversy with pamphlets detailing the horrors of the slums. For the most part the curators ignore missionary campaigns, instead concentrating on housing provision. This varied from the municipal workhouse to common lodging houses. Visitors to the Geffrye can see what 'picking oakum' actually means; the bold may try a replica 'coffin bed' for size.

Prince Albert, in his quest to improve housing for the poor, took up the architect Henry Roberts in the 1840s. Roberts was the honorary architect to the Society for Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes. Large watercolours and a model of his flats for the society open the exhibition. Built near the British Museum in 1849, they still stand today. They illustrate a problem for the reformers: how to design large buildings, for multiple occupation by separate families, without them being liable to Window Tax? A humble fourth-rate family house with six windows or fewer was exempt, a large block for a hundred people would be taxed at a shilling per window. Roberts was commissioned to design model cottages for poor families, which were shown at the Great Exhibition in 1851, the year that the Window Tax was repealed, permitting the building of immense blocks.

Paintings in the exhibition tend to be sentimental rather than controversial, our empathy with photographs is more immediate. Jack London concealed a small camera about him when he lived rough in London. He used his surreptitious photographs to illustrate his People of the Abyss (1903). Photographs, whether taken secretly, or by those in positions of power, allow for no self-conscious posing: a queue of women awaiting free tea, eye the photographer unconcernedly. Almost life-size, their steady gaze is disconcerting. Their ragged clothes not a style statement, but the only ones that they possessed.

Charles Dickens had known the horror of the workhouse and loathed the blacking factory to which he was sent to work. A fragment of a blacking bottle is shown, as is a bowl such as might have been used by Oliver Twist. An unexpected exhibit is a stuffed and mounted stag's head from a Rowton House. The caption claims that they were considered as luxurious as gentlemen's clubs in the West End. Spartan as the establishments of Pall Mall and St James's may be, they are not as grim as Rowton lodgings. Pevsner was not dragged into court: the management of the Rowton Houses were content with an apology and an erratum slip. Sportingly, they sent Pevsner an invitation to spend a night to see for himself. His reaction is not recorded, but one suspects he did not see the joke.

Homes of the Homeless: Seeking Shelter in Victorian London is at the Geffrye Museum until July 12th, 2015.

David Brady is a historian of art, architecture and design.