Curbing the Power of the Popes

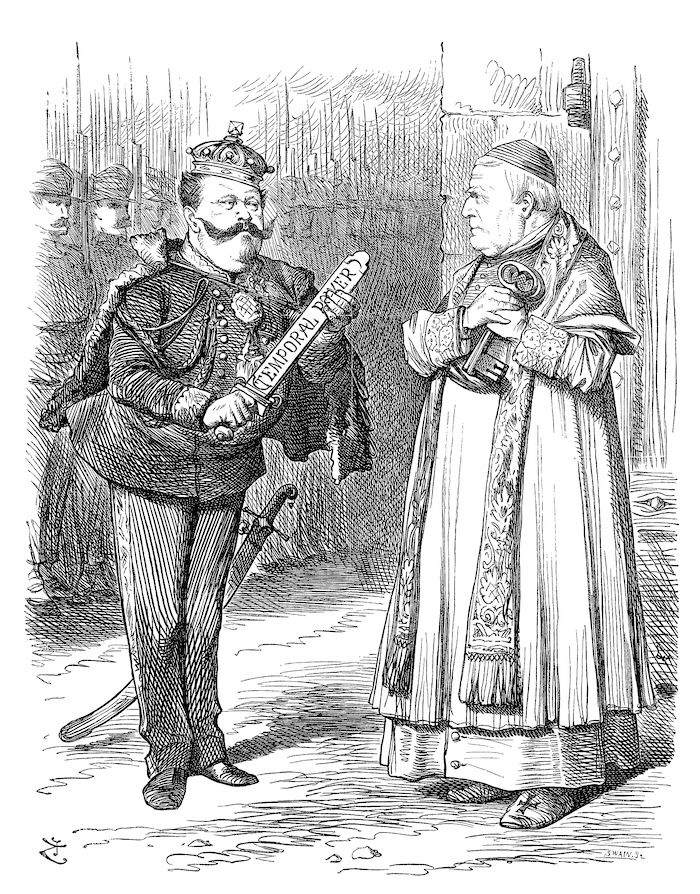

The survival of the papacy has always been dependent on a precarious balancing act between the pope’s religious and secular powers.

In September 1870 concerned and curious Romans gathered at St Peter’s Basilica. Beyond the walls of the Vatican, Pope Pius IX claimed to have been imprisoned in his own realm. For more than a millennium popes had governed territory across central Italy from their capital in Rome. When, in 1861, King Vittorio Emanuele II had united the Italian states to create the nation of Italy, the rump of the Papal States remained distinct. On 20 September 1870, however, the Italian king took the papal capital as his own. For those who questioned the popes’ right to hold worldly authority, it was a just and timely act. For others, the king violated an office sanctioned by God. As a champion of tradition, Pius IX made his feelings plain: it was the pope who had locked himself inside the Vatican Palace. He and his successors would remain ‘prisoners’ until 1929, refusing to recognise Rome as the Italian capital by taking a single step on its soil.

As Italian troops streamed into the city in 1870, Pius IX appeared humiliated. On the Capitoline Hill, papal guards stood behind a barricade of mattresses. One hawker sold straw apparently slept upon by the imprisoned pope. In 1929 the pontiffs would regain their status as temporal rulers of the Vatican City state, but even then the territory granted to them did not extend much further than their self-imposed jail. Nonetheless, the history of the Papal States suggests that losing extensive territories may have been a gift rather than a blow to the papacy. The purpose of the popes’ sovereign status had never been riches or renown – though some popes relished their worldly prestige. Rather, the pontiffs’ temporal power was a means of guaranteeing their independence, free from obligation to secular rulers. When popes were reinstated as sovereigns in 1929 they secured their ability to run the Church as subjects only to God. As rulers of the world’s smallest state, they were liberated from the politicking, scandals, and wars that had blighted their predecessors.

Hallowed ground

From the popes’ emergence in antiquity, their tie to territory was inextricable from their religious role. For most Romans visiting the Vatican Hill in the first and second centuries, however, it was far from an edifying spot. Remote from the pagan city’s religious, political, and commercial centre, Tacitus tells us, ‘promiscuity and degradation throve’. In the hearts and minds of Rome’s first Christians, though, the Vatican was already hallowed ground. In the first century, Saint Peter had died there. While most Romans would have seen him as an anonymous Galilean criminal, Christians saw a martyr whom Christ had elected to lead his Church on Earth. Peter’s death in Rome meant that the first leaders, or bishops, of Rome’s Christian community could call themselves his successors. Rome and the Vatican Hill became fundamental to the claim that the bishops of Rome – later known as popes – are the leaders of the entire Christian Church.

After the emperor Constantine legalised and sponsored Christianity in 313, the link between Peter, his papal successors, and Rome was memorialised in marble and gold. Until then, popes had fulfilled their office in relative obscurity. Now they were installed in splendour at the Lateran, the first Western Christian basilica. On the Vatican, Constantine subsumed the humble shrine to Peter into a vast cathedral inscribed with the imperial name. He gave privileges to priests across the empire, while Rome’s popes enjoyed their own palaces. Soon the popes’ worldly status was so enviable that a pagan aristocrat joked: ‘Make me the Bishop of Rome and I will become a Christian immediately!’

The legalisation of Christianity meant that popes and bishops elsewhere could lead and expand the Church. However, the popes’ new status in Rome and the empire encumbered them with new civic responsibilities. By 324 concerns about territories in the Eastern Roman Empire shifted Constantine’s focus from Italy to Byzantium. From a new capital, Constantinople, he would rule the Eastern empire, leaving Rome and its environs under the emperors of the West, many of whom were weak and unscrupulous. For Germanic tribes seeking wealth and influence, Italy and Rome became tantalising, vulnerable targets. Rome was sacked time and again. Pelagius, a monk who fled in 410, claimed that the city, once ‘the mistress of the world’, now ‘shivered, crushed with fear’. While the Western emperors kept their courts in the relative safety of cities such as Ravenna and Milan, the popes remained in Rome, feeding the hungry, sheltering the displaced, and repairing the city. They not only took on administrative and financial responsibilities, they also filled a vacuum as the people’s figurehead and pastor. When Attila the Hun marched his men into Italy in 452 it was Pope Leo I, not the Western emperor, who rode out to bargain with the man known as the ‘scourge of God’.

Yet despite increasing temporal responsibilities the popes of late antiquity did not gain commensurate political influence. Worse still, the Eastern Roman emperors undermined their religious role. In 476 the last emperor of the West was deposed by the Germanic general Odoacer, who made himself king of Italy. From the early sixth century Constantine’s successors, the Eastern emperors in Byzantium, reclaimed much of the Western empire. They ruled Rome and its environs through delegates called exarchs based in Ravenna, and interfered directly in religious matters. Emperors pushed candidates in papal elections, demanded taxes from the Church, and mandated religious change. In 692 Emperor Justinian II tried to force Pope Sergius I to accept married priests. In 726 Emperor Leo the Isaurian banned the veneration of religious icons, sparking a riot in Constantinople. In a Rome replete with holy images, Pope Gregory II refused to implement the ban. His successor, Gregory III, also defiant, used onyx columns presented to him by the emperor’s exarch to display icons. Far from yielding to this resistance, emperors went on the offensive. Justinian II demanded that Sergius be arrested and tried in Constantinople; one of Emperor Leo’s exarchs planned to censure or even kill Gregory II; Leo himself seized estates from the Church.

These popes were bold as they knew that their religious office was meaningless without independence. Moreover, they claimed divinely sanctioned authority and recognised their popularity over the emperors: Sergius was saved by militias, while Gregory II’s pontificate saw a sweeping rebellion against Byzantine rule. In the early eighth century the threat of yet another invading army – the Lombards – pushed the popes to find more powerful allies and make a more decisive break with Byzantium. When the Lombard king Liutprand seized Sutri, a strategic position on the border of the Roman duchy, a pope would once again ride out to meet the invader. In 728 Gregory II persuaded Liutprand to relinquish the territory as ‘a donation to the blessed Apostles Peter and Paul’, circumventing the Eastern emperor. The popes’ relationship with the Lombards would prove rocky, yet their negotiations led to the clear recognition of papal rule in and outside of the Roman duchy. Seeking a more stable alliance in the 750s, Popes Zachary and Stephen II looked north to the recently converted Franks. The Frankish king Pepin the Short and his son Charlemagne would drive out the Lombards. Moreover, they recognised the popes as the governors of a huge swathe of Italy, stretching up to the River Po. Their treaties made no mention of the Byzantine authorities who nominally ruled the land.

Political popes

With the keys to cities across Italy laying on Saint Peter’s tomb in Rome, the popes became sovereigns of the Papal States and autonomous from the Byzantine emperors. Ironically, their new status embroiled them increasingly in secular matters, even as they sought to protect their religious office. Both Liutprand and Pepin knew the political benefits of posturing as guardians of the papacy. Through his alliance with Pope Zachary, Pepin was able to legitimise his contested position as king of the Franks. Stephen II went further, granting Pepin and his heirs the additional title ‘Patrician of the Romans’. In 800 Pope Leo III crowned Pepin’s son Charlemagne the first Holy Roman Emperor.

Though the Franks were their official protectors, the pontiffs had to work with the Roman aristocracy and lords elsewhere to administer their Papal States. Moreover, the popes themselves were often entangled with the temporal actors who sought to influence and even choose the man who sat on Saint Peter’s throne. There had been violent tussles for the papacy since Constantine’s sponsorship of the Church. By the early medieval period the popes’ influence was widely recognised and conclaves and entire papacies became marred by bribery, scandals, and brawls. In the tenth century Liutprand of Cremona claimed that Teofilatto, Count of Tusculum, and his wife, Theodora, used their daughter to secure their influence by having her seduce Pope Sergius III, bearing him a son who would become Pope John XI. Liutprand may have exaggerated Teofilatto’s misdeeds; he was an ally of their rival, Otto of Saxony. Still, other stories from the period paint an equally seedy picture. Pope John XIII had the prefect of Rome stripped naked and paraded through the city on the back of a mule as punishment for opposing his election.

Reforms instigated by Pope Gregory VII in the 11th century sought to enforce discipline and assert the popes’ supremacy over political actors, yet papal politicking continued. Despite the popes’ long history in Rome, the people of the city were far from indifferent to their power plays. In 1143 a revolution broke out when Pope Innocent II undermined a Roman plan to take the nearby hill town of Tivoli, cutting his own deal to protect the inhabitants in exchange for their fealty. The Romans demanded that the pope be stripped of all political authority and revived the ancient senate on the Capitoline Hill. Innocent took to his bed and died. His successors only re-established themselves in Rome 45 years later, with the help of the Holy Roman Emperors. When Pope Clement III finally returned in 1188 he had to accept the continued presence of the senate that represented the Commune of Rome. This was not the last time that Romans would protest the politicisation of the papacy. In the 14th century a power struggle between Pope Boniface VIII and King Philip the Fair of France led to the death of the pope (after being imprisoned by Philip’s men) and the transfer of the papacy to Avignon. Noble families in and around Rome seized the opportunity to extend their influence, leading to bloodshed and chaos. Absent from Rome for 60 years, the popes were blamed. Authors such as Dante and Petrarch claimed that the pontiffs had become pawns of the French king, debasing their office and reducing Christ’s Church to a ‘Babylonian whore’.

Comeback

It was a happy day for many when a pope was restored to Rome in 1420. Martin V, a member of the city’s powerful Colonna family, rode into Rome on horseback flanked by jesters and roaring crowds. The years preceding Martin’s election had further undermined the papal office. When cardinals had met to elect a pope in 1378, following the death of Gregory XI, a baying mob had looted the Vatican Palace, threatening to ‘kill and cut to pieces’ the cardinals voting inside. After the conclave elected Pope Urban VI, a large contingent abandoned him, declaring that they had acted under duress. The claim sparked the Great Western Schism, which saw three popes ruling at the same time, in Rome, Avignon, and Pisa. The fact that it took a council of bishops, rather than the usual conclave of cardinals, to elect Martin V also harmed papal authority, enthusing ‘conciliarists’ who argued that synods of bishops held equal or even higher authority than the pope.

Soon, however, the popes appeared to have made a strong comeback, in Rome and the Papal States. With the help of family and allies, Martin V subdued the feudal lords who had acted like princes in the popes’ absence. His successors would go to war with the Italian authorities that had encroached on papal lands. After 1495 the popes would even hold their own against major international powers, as France and the Spanish Habsburg dynasty vied for hegemony alongside local allies in the Italian Wars. Some popes seemed born for the role of defenders of the Papal States. In 1495 Alexander VI allied with the Holy Roman Emperor, Republic of Venice, and Ferdinand of Aragon. Capitalising on anti-French sentiment, he rolled back the French occupation of the Kingdom of Naples, protecting its status as a papal fief. Pope Julius II was even more formidable. In 1511, at the age of nearly 70, he led his army through thick snow to defeat French forces at the Siege of Mirandola. Writing in 1438 the humanist Lapo da Castiglionchio the Younger described the papal court as a centre of international power, writing that ‘all things are deferred to the pope’. The claim was somewhat exaggerated for Capo’s day and later popes’ political influence fluctuated. However, during the 16th and 17th centuries the alliance and blessing of the pontiff were sought via embassies from as far afield as the Congo, while popes sent out their envoys to cities from Moscow to Alexandria.

The pope diminished

Despite the restoration of papal authority in Italy, popes could not escape the innate conflict between their religious and temporal roles. Many failed to live up to the complex demands of dual authority. Before his election in 1523 Pope Clement VII was respected as the shrewd second-in-command to his cousin, Pope Leo X. But when he became pope, Clement wavered in indecision – with disastrous consequences. When the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, seemed overly ambitious to influence the Church as well as extend his territories, Clement turned on his ally, sparking a conflict that led to another Sack of Rome. Meanwhile objections to the worldliness of popes threatened their office more than ever. In a dialogue probably written by Erasmus in 1514, Pope Julius II is denied entrance to heaven by Saint Peter when he arrives stinking of booze, boasting of treasures, and wearing armour stained with blood. Martin Luther would also denounce the pope for having ‘the wealth of the richest Crassus’. At first, Luther only called for the reform of the Church, but his criticisms chimed with the concerns of princes weary of papal interference. Within decades dissatisfaction and dispute sparked Reformations that saw England, Scotland, Scandinavia, and parts of France and the Holy Roman Empire reject the religious and temporal authority of the pope.

The pope would keep his own states intact through the 17th and 18th centuries, but his influence over both religious and worldly matters was irreversibly diminished. This was obvious in the aftermath of the Thirty Years War (1618-48), which saw religious conflicts combine with questions of territory and sovereignty and entangled European powers from Spain to Sweden. When political leaders realised that only compromise and pragmatism could stem the bloodshed, Innocent X, a pope who refused to negotiate with ‘heretics’, was excluded from the negotiating table. The marginalisation of the popes on the world stage continued throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Even Catholic princes such as the Habsburgs and Bourbons declined the popes’ offers to mediate in disputes. Meanwhile, the ideas of the Enlightenment shook the beliefs that underpinned traditional powers. When Napoleon invaded the Italian peninsula in 1797, he did not even think it necessary to conquer the Papal States. After forcing Pope Pius VI to sign the financially crippling Treaty of Tolentino, he apparently declared that ‘the old machine will fall apart by itself’.

Moral authority

Napoleon’s words must have seemed prophetic when Pius IX surrendered to Vittorio Emanuele II in 1870 and the white flag was raised over St Peter’s Basilica. More than a millennium had passed since Pepin the Short offered himself as Rome’s protector, and the pope had few allies. French troops had defended Pius from invasion and revolution, despite frustration with his conservatism, but they abandoned Rome in August 1870 when the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Confined to the Vatican, denuded of their lands, it seemed that Pius IX and his successors would now have a solely religious role. They endorsed new devotions and issued texts on the great moral questions of the age. Yet there was still political weight to the affection and influence that the popes enjoyed among Catholics all over the world. When Pius IX refused to give up the Quirinal Palace after Emanuele’s seizure of Rome, the king declined to move in, fearing a backlash from the people, many of whom resented the dispute, known as ‘the Roman Question’, between the Italian state and the papacy.

In 1929 it was the popes’ persistent prestige that helped them to win back their sovereign status. By that time, the fascist leader Benito Mussolini was prime minister of Italy. In the pursuit of honour and popularity Mussolini reconciled the Italian state and the Catholic Church through the Lateran Accords of 1929. By giving Pope Pius XI a state of around 440,000 square metres, he claimed to have succeeded where his predecessors had failed, restoring ‘the true and fitting sovereignty of the pope’. As with so many earlier political deals, the pope’s negotiations with Mussolini would blight his moral authority. For the four popes who had ruled as ‘prisoners in the Vatican’ after Pius IX, however, the value of regaining sovereign status had been starkly underlined. During the First World War Pope Benedict XV had found himself powerless, his cries for peace falling on deaf ears. The Italian state censored incoming communications and undermined the pope’s neutrality by requisitioning the Austrian Embassy to the Holy See. The Vatican State granted to Benedict’s successor may have been minuscule, but it guaranteed the popes ‘a liberty and independence not only actual but visible to all’. Despite past negotiations with fascist powers, the papacy continues to possess a moral authority that leads political leaders to call upon popes for approval and verbal intervention. Yet as rulers of a state too small to trouble political actors, popes are spared the burdens that long undermined the religious authority at the heart of their office.

Jessica Wärnberg is author of City of Echoes: A New History of Rome, Its Popes and Its People (Icon, 2023).