The Unhappy Mansion

Bedlam was a constant in art and literature throughout the 18th century. In it, madness was otherworldly, bestial, pitiable and female – a mirror for concerns about society.

‘Bedlam’, London’s first public mental hospital, is typically understood as a byword for chaos, mania and disorder. While its mythic and often ambiguous status has inspired numerous and varied representations across art, drama and literature since the 17th century, in recent years ‘Bedlam’ – both the geographical site and a figurative concept – has become the focus of academic debate regarding the ethics and issues surrounding mental health. Historically, Bethlem has always provoked a reaction, serving as an intriguing site of conflict and debate and representative of wider developments in society’s understanding of madness. Today, artworks featuring the hospital and its ‘unhappy Bedlamites’ continue to provide historians of psychiatry and visual culture with ample interpretations of how the mad were viewed. Within these, perhaps none prove as vivid and contradictory as those which explore the hospital’s persona in the 18th century; a time when its infamous practice of allowing visitors through its doors to gawp at the mad was in a state of fascinating flux.

‘Bedlam’, London’s first public mental hospital, is typically understood as a byword for chaos, mania and disorder. While its mythic and often ambiguous status has inspired numerous and varied representations across art, drama and literature since the 17th century, in recent years ‘Bedlam’ – both the geographical site and a figurative concept – has become the focus of academic debate regarding the ethics and issues surrounding mental health. Historically, Bethlem has always provoked a reaction, serving as an intriguing site of conflict and debate and representative of wider developments in society’s understanding of madness. Today, artworks featuring the hospital and its ‘unhappy Bedlamites’ continue to provide historians of psychiatry and visual culture with ample interpretations of how the mad were viewed. Within these, perhaps none prove as vivid and contradictory as those which explore the hospital’s persona in the 18th century; a time when its infamous practice of allowing visitors through its doors to gawp at the mad was in a state of fascinating flux.

The hospital had allowed visitors since the late 1600s, providing opportunities for artists and writers alike to view and depict the mad. Yet, as visiting continued, viewing the insane at Bethlem became problematic. As artists used their work to display their confusion and castigations about both mental health and the institution itself, Bethlem become a place where amusement, morality and the ethics of viewing collided.

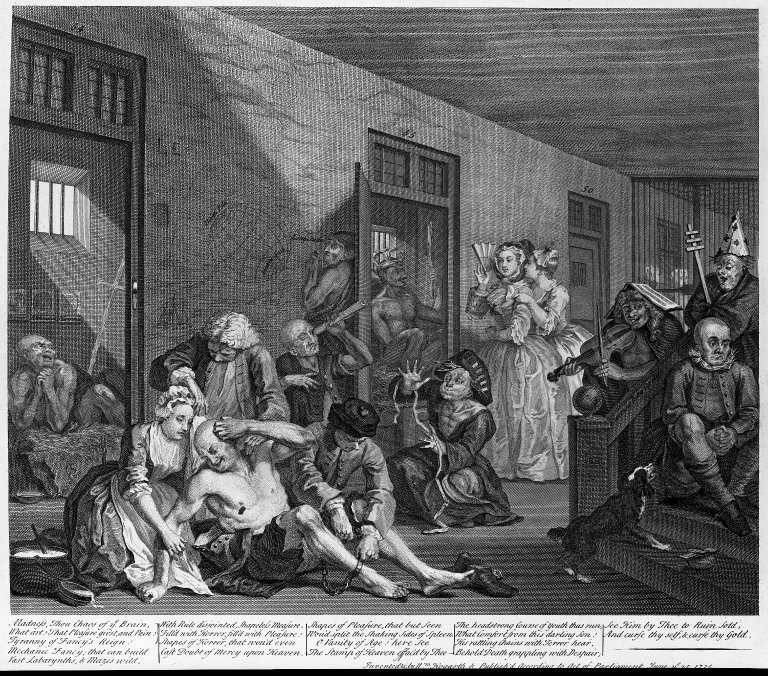

Works such as the final plate in William Hogarth’s series, A Rake’s Progress (1733-34), show the complexity of reactions to the hospital, alongside the varied conceptions of madness. Hogarth used his engravings to comment on the follies and hubris of Georgian society, with his protagonist’s demise at Bedlam serving as the ultimate punishment. The Rake is shown among a menagerie of strange, otherworldly characters: a magician, emperor, musician and astrologer all sit side-by-side within the frame. Among this motley line-up, two fashionably dressed women unceremoniously enjoy the spectacle of a madman in one of the cells. Hogarth’s etching stresses how a visit to ‘Bedlam’ was understood predominantly as a tourist activity, part of a composite of spectacular scenes that created an intensely visual experience within the city.

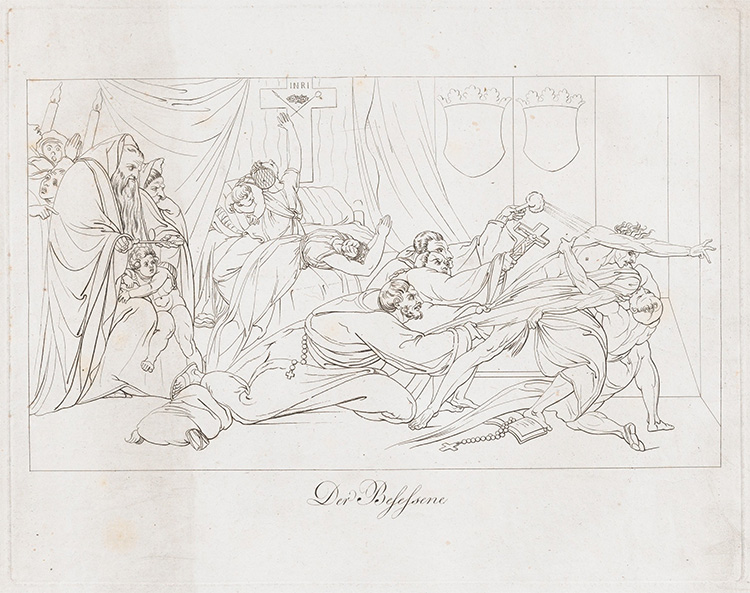

Nebuchadnezzar recovering his reason (1781) shows a naked, hairy figure with claw-like nails, while Fuseli’s drawings from Rome’s San Spirito Hospital depict a scene of barely human figures, scuttling along the asylum’s floor. In a similar sense, within representations of Bethlem, the mad were often portrayed as too terrifying to view. In his Man of Feeling (1771), Henry Mackenzie speaks of clanking chains, wild cries and how these raving animals were separated from the more ‘normal’ inmates. Alongside a trip to Bartholomew’s Fair or the anatomy theatre, the mad had become exhibition pieces, commonly depicted as bestial, animalistic and freakish. Perhaps most potent of these representations was Caius Gabriel Cibber’s stone statue of Raving Lunacy (1680), which flanked Bethlem’s gates and loomed over guests on arrival. The epitome of frenzied and menacing raving mania, Cibber's statue was a warning for guests, designed to provoke the tourist gaze whilst being regarded at a safe distance.

But Cibber’s sculpture had a twin: Melancholic Lunacy, the other side of madness for the 18th-century viewer. Pensive, morose and neurotic, this was the more fashionable madness in the 18th century, particularly when considering the wave of sentimentalised fiction that surfaced in the 1740s. Literary works such as Pamela and Clarissa by Samuel Richardson were part of this new ‘Age of Sensibility’, which emphasised strong feeling, emotionality and so-called ‘feminised’ traits. As the art historian Jane Kromm stresses, women were seen as weaker and prone to allow their newly sensitised feelings to topple into melancholic mania. Within this literary framework, madness steadily became reconfigured as a decidedly female malady.

But Cibber’s sculpture had a twin: Melancholic Lunacy, the other side of madness for the 18th-century viewer. Pensive, morose and neurotic, this was the more fashionable madness in the 18th century, particularly when considering the wave of sentimentalised fiction that surfaced in the 1740s. Literary works such as Pamela and Clarissa by Samuel Richardson were part of this new ‘Age of Sensibility’, which emphasised strong feeling, emotionality and so-called ‘feminised’ traits. As the art historian Jane Kromm stresses, women were seen as weaker and prone to allow their newly sensitised feelings to topple into melancholic mania. Within this literary framework, madness steadily became reconfigured as a decidedly female malady.

Mad Girl by Thomas Lawrence show a weeping female figure, a wreath of straw on her head to signify ‘Bedlam’. Similarly, Crazy Kate by Thomas Barker of Bath shows a lost, helpless lunatic, designed to inspire sympathy and feeling. Increasingly, paintings and prints began to rely on an iconography which made the madwoman sentimental; in comparison, a raving maniac now proved too ghastly to view. In 1785, William Cowper’s poem The Task set out the subject of Barker’s painting. ‘Crazy Kate’ is a damaged heroine driven mad by the loss of her lover, who soon became the archetypal figure of the madwoman. These accounts seek to bring the madwoman closer to those visiting Bethlem, in order to inspire charity and humanity, a far cry from the terrifying, animalistic representations of the insane as before.

In 1770 Bethlem closed it doors for good; in the words of the historian Jonathan Andrews, ‘the fun had gone out of looking at the insane’. Instead, a conception of madness in line with a new, sensitised model of looking, was encouraged. The ideal viewers of the mad – be it virtual or through occasional, pre-arranged visits to the asylum – were sensitive, humane and caring. This new way of viewing was expressed and extolled in periodicals and newspapers, in keeping with developments in how Georgian Britons were supposed to behave.

A Rake’s Progress in 1762, which sees a coin bearing a wild Britannia on the asylum’s back wall – became common during the latter decades of the 18th century. Rather than represent the symbol of Britain as a powerful, headstrong female, Hogarth subverted traditional iconography and portrayed her in bedraggled, unsettling terms. While some commentators argue that Hogarth’s inclusion of this troubling symbol speaks of a country in crisis, Kromm is adamant that this was a comment on wider parliamentary issues and the irresponsibility of government. Other images, such as Robert Edge Pine’s terrifying Madness from 1770, agree with this notion, showing the madwoman in an unforgiving, startling fashion, with a crown of straw on her head to locate her within Bethlem’s walls. As political factions fought in the shadow of George III’s madness and national insecurities raged concerning war with France, the female madwoman was used as a weapon to evince the consequences of a country in political and national upheaval.

Anna Jamieson is a freelance writer and recently finished her Masters degree in History of Art at Birkbeck, University of London.