Rothschild Renaissance

Dora Thornton, curator of the Waddesdon Bequest and Renaissance Europe at the British Museum, on her role in the creation of a new, permanent and public home for one of the great private collections.

Curators at the British Museum think with things. In my case, Renaissance things; Rothschild things. In curating a new gallery for the Waddesdon Bequest – a treasury of intricate and precious art objects from old Europe which was left to the British Museum by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild in 1898. I have been musing about the relationship between the Rothschilds and the Renaissance. Like the Randlords, railway magnates, bankers and armament manufacturers, who shaped the modern world in the 19th century, the Rothschilds flocked to the Renaissance. As the author and ceramicist Edmund de Waal put it to me recently: 'You are trying to establish yourself as a family that is not going anywhere else; you are not wandering Jews, you are staying put. You have adopted a country and you are going to create a collection to be worthy of that adoption. You collect in order to tell the people around you that you are not going anywhere.'

Curators at the British Museum think with things. In my case, Renaissance things; Rothschild things. In curating a new gallery for the Waddesdon Bequest – a treasury of intricate and precious art objects from old Europe which was left to the British Museum by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild in 1898. I have been musing about the relationship between the Rothschilds and the Renaissance. Like the Randlords, railway magnates, bankers and armament manufacturers, who shaped the modern world in the 19th century, the Rothschilds flocked to the Renaissance. As the author and ceramicist Edmund de Waal put it to me recently: 'You are trying to establish yourself as a family that is not going anywhere else; you are not wandering Jews, you are staying put. You have adopted a country and you are going to create a collection to be worthy of that adoption. You collect in order to tell the people around you that you are not going anywhere.'

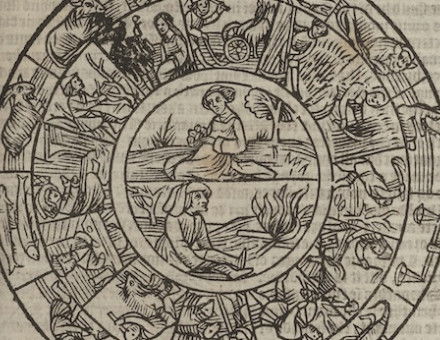

But why the Renaissance? Baron Ferdinand used these objects to tell stories about European history and the role of his family within it. In using art to form new codes of behaviour, the Rothschilds evoked the great merchant bankers of the 16th century, such as the Medici and the Fugger. As a European dynasty which had dominated half the known world in the 16th century and who expressed their status and power through the collecting and display of art, the Habsburgs were also obvious models. Comparisons between the court treasuries of Europe in Kassel, Dresden, Vienna, Ambras and Munich demonstrated how the Rothschilds shaped their own Kunstkammern. Provenance mattered. Conrad Meit's exquisite miniature busts of around 1515, showing Margaret of Austria and her husband, Philibert of Savoy, were prized not just for their intrinsic quality but because they had come from the Kunstkammer of Rudolf II of Prague. A miniature tabernacle, carved in boxwood around 1510 in the northern Netherlands, comes with its custom-made case incised with the arms of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. That association added to its appeal as a virtuoso sculpture, which unfolds like a flower in the hand as an interactive aid to prayer. A nautilus cup in the Bequest, made from a nautilus pompilius shell from the Indo-Pacific, carved in Guangzhou, traded by the Portuguese and set in northern Europe into exotic dragon mounts, was another typical Kunstkammer object, one which fused Old and New Worlds and made distant places tangible. It was emblematic of the European tradition of curiosity and dreaming which Baron Ferdinand could tease out for visitors to his 'Renaissance Museum' at Waddesdon Manor. Displayed in the New Smoking Room, this select collection was a stage-set for the kind of enlightened corporate entertaining for which the house was famous. Seen through wreaths of cigar smoke, the objects had a role to play in the social life of the space.

The Rothschilds rose from the Frankfurt ghetto within two generations to become bankers to the world. Baron Ferdinand wrote about social progress in which he saw his family and the art market as the drivers: 'Newly-formed collections are generally more accessible in their new homes than in their former secluded retreats. They contribute, not a little, to dignify their new residence; they attract the more enlightened and intelligent portions of society, who, in their turn, attract the fashionable throng. Thus brilliant gatherings are formed … [which] may lead to the social and political development of a future age … Collectors may deplore the fact but it should be a source of gratification to the public that most fine works of art drift slowly but surely into museums and public galleries. In private hands they can afford delight only to a small number of persons.' Ferdinand saw himself as an actor in the historical process by which private collections moved inexorably into the public domain. He went further in declaring that the public opening of the British Museum, to which he was to leave his cabinet collection, marked 'the establishment of art as an institution'.

The thinking for my book, A Rothschild Renaissance: The Waddesdon Bequest, has underpinned everything we do in the new display and on the web. Funded by the Rothschild Foundation, the gallery reconnects the Bequest both with Waddesdon as a Rothschild creation and with the history of the British Museum. Designed by Stanton Williams, it is part of the grand suite of rooms designed by Robert Smirke in the 1820s on the ground floor. This starts with the King's Library, reimagined as the Enlightenment Gallery in 2003, then moves to the old Manuscripts Saloon, which was remodelled in 2014 as a gallery devoted to collectors and collecting from the 19th century to the present. That suite will now culminate in the Waddesdon Bequest in the Middle Room, the original Reading Room of the British Museum in the time of Charles Dickens. It is part of a curatorial axis which presents the British Museum as a collection of collections. We have aimed to create a calm but connected space, which rewards looking. With the book and ambitious digital programme, the gallery presents a snapshot of the self-fashioning of a new dynasty in 19th-century Europe.

The Waddesdon Bequest Gallery opens to the public on June 11th. It is located in Room 2A of the British Museum.