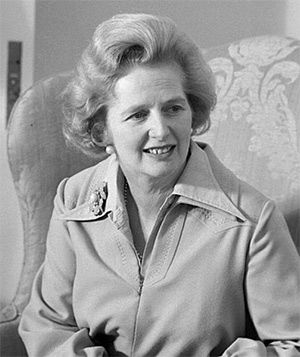

Margaret Thatcher's Career in Perspective

Roland Quinault offers an appraisal of the Iron Lady's legacy.

The death of Margaret Thatcher has unleashed a deluge of media comment on every aspect of her personality and politics. There has been general agreement that she was the most important prime minister in the second half of the twentieth century and one who made a distinctly personal impact on British politics. While there are good grounds for that assessment, both her critics and her admirers have exaggerated the nature of her contribution and achievement in various respects.

The death of Margaret Thatcher has unleashed a deluge of media comment on every aspect of her personality and politics. There has been general agreement that she was the most important prime minister in the second half of the twentieth century and one who made a distinctly personal impact on British politics. While there are good grounds for that assessment, both her critics and her admirers have exaggerated the nature of her contribution and achievement in various respects.

Her rise from modest beginnings to the premiership followed in the footsteps of her three prime ministerial predecessors. Like Wilson and Heath she went from a local selective school to Oxford, whereas Callaghan went to neither a grammar school nor university. Thatcher’s gender was not much of a political disadvantage either. At Oxford, she was the third woman to become President of the university Conservative association. At the 1950 general election she was one of 126 female candidates – a number not exceeded until 1974. Although not elected, she gained considerable press attention as a young and attractive candidate. She subsequently married a very wealthy businessman, which enabled her to pursue both a legal and a political career. It was her barrister friend and Tory MP, Airey Neave, who masterminded her successful party leadership campaign in 1975.

Before that campaign, Thatcher was a loyal supporter of the official party line. It was only the mistakes of Heath in his handling of the miners’ strike and of Callaghan with respect to ‘the winter of discontent’ that enabled Thatcher to become first the leader of her party and then the first female prime minister. But Barbara Castle had already demonstrated that a strong-minded, straight talking, woman could hold her own with men on the national political stage. Once in office, Thatcher relied on old-fashioned feminine charms as well as her robust powers of argument to win over her male Cabinet colleagues to her point of view. She promoted very few women to ministerial posts and did little to advance the prospects of women whether in politics, the economy or society.

Thatcher is widely regarded as a conviction politician who put principle before expediency. Before the 1979 general election she declared that she would not tolerate dissent and denounced the idea of consensus. Yet once in office, she included a wide range of Tories in her Cabinet and she relied heavily on the consensual skills of her deputy, Willie Whitelaw. For much of her premiership, moreover, caution was the hallmark of her policies. Her trade union reforms were gradual, while she avoided major changes to the National Health Service and the welfare system. Even her government’s privatisation of industry was selective for the coalmines, the railways and the Post Office remained in the public sector. Despite her rhetorical flirtation with the small-State views of Sir Keith Joseph and others, she followed her predecessors in strengthening, rather than weakening, the power of central government.

Claims that Thatcher was an anti-establishment figure – a right-wing radical, rather than a Conservative – are much exaggerated for her policies usually had an historical pedigree. Her belief in free market economics and in individual enterprise and responsibility had their origins in Victorian Liberalism – hence her desire for a return to ‘Victorian values’. Her support for leasehold enfranchisement and the sale of council houses to their tenants promoted the creation of a ‘property-owning democracy’, which had long been a Conservative objective. She was also conservative in her opposition to reform of both the electoral system and the House of Lords. Her strong support for the Union of the United Kingdom was also in accordance with Tory tradition, while the abolition of the Greater London Council reflected the Conservatives old mistrust of a unitary local authority for the capital. Thatcher’s trade union legislation followed on in the wake of earlier, though less successful, reforms by Edward Heath. Her attitude to the 1984-5 miners strike closely resembled that of Baldwin to the 1926 General Strike. Like Baldwin, she regarded the strike as a politically motivated challenge to democratic government and took measures before and during the strike to ensure that it did not succeed. Even the introduction of the Community Charge – a flat ‘poll tax’ on all residents of a kind not levied for centuries – reflected her determination to protect the financial interests of ratepayers, who had long been the backbone of the Tory grass roots.

Thatcher is often represented as a warrior premier – the ‘iron lady’ and a modern personification of Britannia or Boudicca. Yet her bellicosity has been much exaggerated. The Falklands war was not of her choosing and it was the pusillanimous stance of her government regarding the sovereignty of the islands that encouraged the Argentine Junta to invade them. Her decision to despatch a task force to regain the islands reflected the strength of public indignation and she was far from confident that it would succeed. Success in the Falklands war boosted her confidence and reputation but it did not tempt her to engage in further military operations. She subsequently agreed to surrender Hong Kong – a much more valuable colony than the Falklands – to China despite the reservations of its people. While Thatcher believed – like all premiers during the cold war - in the need for military strength in the face of the Soviet threat, she also sought détente when conditions were right. Consequently she invited Gorbachev to visit Britain and famously concluded that ‘we can do business together’.

With respect to Europe too, Thatcher’s stance has generally been misrepresented. She has been widely regarded as a ‘Eurosceptic’ or ‘Europhobe’ but for many years she was an enthusiastic supporter of the European Union. As a member of Heath’s government she supported Britain’s accession to the European Economic Community and she voted to stay in the union in the 1975 referendum. As prime minister she fought, hard and successfully, to lessen Britain’s financial contribution to the European Budget but she strongly supported the 1985 Single European Act, which promoted a free market within the EU. She also actively supported the accession of Spain and Portugal and later the ex-Communist countries of Easter European into the union. Although her speech at Bruges, in 1988, was critical of the bureaucracy and undemocratic features of the EU, neither then nor later did she call for Britain to withdraw from the union. She was wanted to redirect the European train but not to jump off it.

Ironically, Thatcher’s legacy was, in many respects, more ‘Thatcherite’ than her own ministry. John Major extended privatisation to sectors where she had feared to tread, while Tony Blair assumed the mantle of an ‘iron man’ in his pursuit of an interventionist foreign policy that went far beyond what she had countenanced. Even Gordon Brown adopted greater financial de-regulation than she had approved and invited her to tea at Downing Street. Each of them was misled by an image of Thatcher that exaggerated her characteristics and simplified her policies. In reality, her contribution to British politics was subtler but also less game changing than has been alleged.