Temple of Power

Roger Hudson sails past a half-built Battersea Power Station and on to its slow decline.

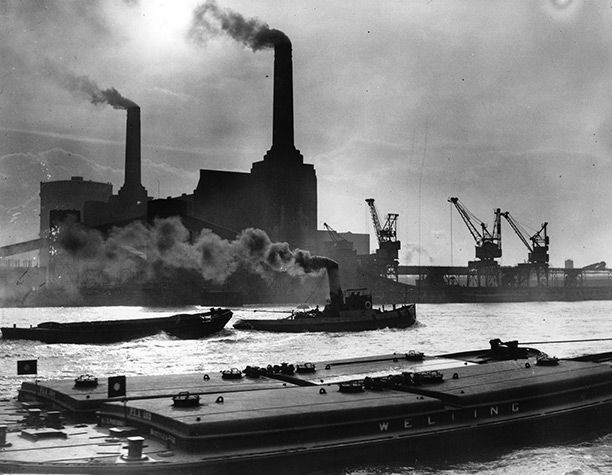

A striking, dramatically lit shot of Battersea Power Station on the Thames, opposite Chelsea, photographed in 1937. It takes a moment or two to realise something is missing: it only has two chimneys, not four, and does not bulk as large as the Battersea we know. In fact it was a two-stage project and the second half was only erected in the 1950s. Did the photographer seek to contrast old with new, catching the coal-fired tug towing a lighter upstream in front of this symbol of the electric age? Probably not: it just helped his composition and anyway, at its height, the power station itself consumed a million tons of pulverised coal each year. This came mostly via the Thames in colliers from South Wales and Tyneside. The river also furnished the 340 million gallons of water that passed through the workings of the power station each day. The colliers were called flat-irons or ‘flatties’ and their funnels could be lowered so they fitted under the Thames bridges. Four of the cranes, with grabber buckets used for unloading the coal from the ships’ holds onto conveyor belts, can be seen.

A striking, dramatically lit shot of Battersea Power Station on the Thames, opposite Chelsea, photographed in 1937. It takes a moment or two to realise something is missing: it only has two chimneys, not four, and does not bulk as large as the Battersea we know. In fact it was a two-stage project and the second half was only erected in the 1950s. Did the photographer seek to contrast old with new, catching the coal-fired tug towing a lighter upstream in front of this symbol of the electric age? Probably not: it just helped his composition and anyway, at its height, the power station itself consumed a million tons of pulverised coal each year. This came mostly via the Thames in colliers from South Wales and Tyneside. The river also furnished the 340 million gallons of water that passed through the workings of the power station each day. The colliers were called flat-irons or ‘flatties’ and their funnels could be lowered so they fitted under the Thames bridges. Four of the cranes, with grabber buckets used for unloading the coal from the ships’ holds onto conveyor belts, can be seen.

In 1920 there were 730,000 electricity consumers, but by the 1930s the number was up to nine million. What made this possible was Parliament’s decision in 1925 to establish a publicly-owned high-voltage national power grid, a standardised system to enable the mixture of voltages and frequencies, which had evolved piecemeal up until then, to be replaced. Several smaller London companies formed the London Power Company and decided to build big, with Battersea as the first of the new generation of generators, on the site of some old reservoirs. The often-accepted picture of the 1930s – queues of unemployed, hunger marchers, etc – may have been true enough in the North but in the Midlands and the South things were soon buzzing and humming after the slump of 1931. It was clean electricity which made those noises possible, coming out of the new picture palaces, the vacuum cleaners, radios and radiograms; powering the bar fires, toasters, cookers, immersion heaters, washing machines, commuter trains; lighting up the standard lamps, the new factories where these electrical goods were made and the neon advertisements for them. This was the decade when poems were written about pylons.

To defuse the nimbys Giles Gilbert Scott, grandson of George Gilbert Scott, who built the hotel at St Pancras and the Albert Memorial, was hired to clad Battersea’s steel frame in something becoming. Thus was created the largest brick building in Europe, supplying a fifth of London’s electricity and voted in 1939 as Britain’s second-best modern building after the Peter Jones department store in Sloane Square. When another large power station was required lower down the Thames at Bankside after the war, he used brick again, but managed with only one chimney, out of deference to neighbouring St Paul’s.

Battersea ceased generating in 1983, its machinery wearing out and coal going out of fashion. Since then it has been a snare and a temptation to a succession of developers with eyes bigger than their stomachs. Its boiler house roof was removed in the late 1980s, so machinery could be taken out, and this has done nothing to stop rot and decay within what is a listed building. Arguments go back and forth over whether structure and chimneys can be repaired or must be knocked down and rebuilt. An Irish developer was the last to throw in the towel and now a Malaysian consortium is chancing its arm. If it does manage to move forward one of the lesser sums it must confront is the £200 million it has to contribute to the Northern Line underground spur, promised to rejuvenate this area of Nine Elms. Who knows, perhaps the announcement that the new US embassy is to be built in nearby Vauxhall will be enough to float this neighbouring leviathan, too.