Paris’ Problem with the Dead

Catacombs, cemeteries and the dead as a revolutionary force.

There’s a scene in the US political thriller House of Cards in which Claire Underwood, played by Robin Wright, goes for a run in a cemetery and, to her shock, is berated for doing so by an elderly woman who is there to mourn. Aside from underlining the moral complexity of Underwood’s tough-minded character, the scene speaks to an uneasy sense that, at least in advanced capitalist nations such as the UK and the US, where the processes of secularisation have recently been distinctly uneven, we don’t quite know how to behave in places that, in Erin-Marie Legacey’s phrase, make space for the dead. I can remember provoking a similar morally outraged reaction when, a decade ago, I took my small children to the local cemetery for a picnic.

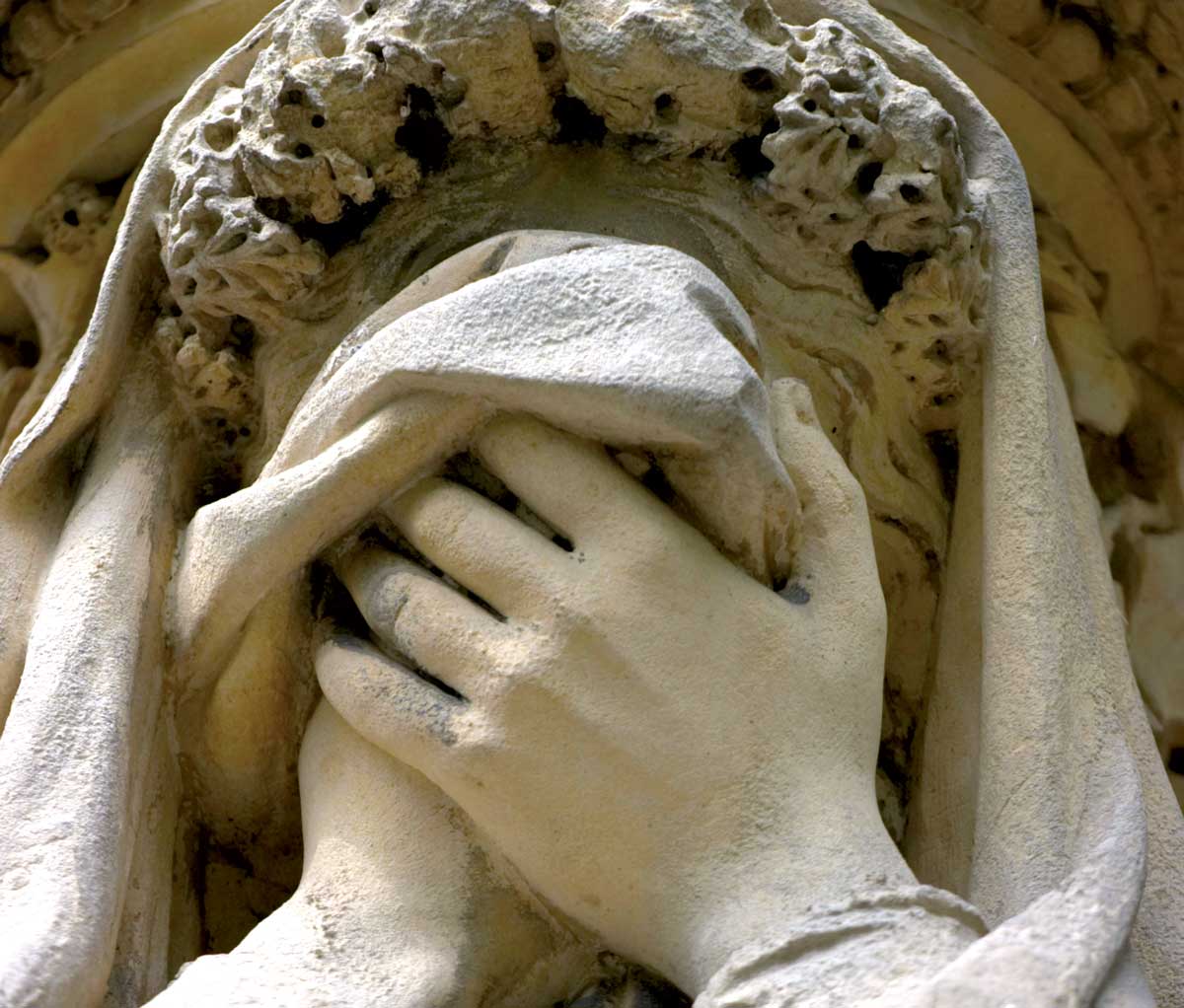

The adjective ‘liminal’, from the Latin limen, a ‘threshold’, has for a long time been something of a cliché in academic accounts of space, particularly among proponents of postmodernism; but for once it seems genuinely appropriate. The uncertainty and unease we feel in relation to cemeteries is partly because, in their social and symbolic functions, they are so richly ambiguous (the French historian Michel Foucault recognised this when he offered cemeteries as a classic example of those ‘other’ places that, in troubling the prevailing, broadly rationalist distribution of space in society, he classified as ‘heterotopias’). Cemeteries occupy a sort of border territory between a series of oppositions that structure post-Enlightenment thinking. They disturb convenient distinctions between, among other things, the living and the dead, this world and the next, the religious and the secular, the country and the city, the private and the public.

It is one of the strengths of Legacey’s perceptive monograph on the formal, ritual sites of death in post-Revolutionary Paris, which include the Catacombs and the short-lived Museum of French Monuments, as well as Père Lachaise Cemetery, that it is sensitive to their contradictoriness both as social spaces and as repositories of what she calls the ‘social imaginary’. The cemeteries and Catacombs of the French capital during the 50-year period from 1780, when a royal ordinance first declared the Cemetery of the Holy Innocents a danger to public health, functioned as forceful agents of emerging notions of rationality, sociability and national unity, especially in so far as these entailed a rejection of the Old Regime. Although the Catacombs beneath Paris, which opened to the public in 1809, proved predictably thrilling in their gothic associations, the spaces of the dead so sensitively excavated by Legacey thus conducted utopian energies as well as unsettling ‘heterotopian’ ones.

Père Lachaise itself, for example, which is at the dead centre of this book so to speak, was established in 1804 not only as a bucolic space that, with its picturesque landscape of tombs and blossoming trees, promised to efface Parisians’ nightmarish memories of the stinking, suppurating burial pits and graveyards that had threatened public health before and in the immediate aftermath of the Revolution, but as a site of new forms of education and social interaction. ‘Conflating public and private space’, it was a place, Legacey argues, where ‘nineteenth-century Parisians took advantage of the cemetery as a powerful liminal zone in the city’.

Legacey has scrupulously examined the literature on cemeteries from the early 19th century, including influential guidebooks by C.P. Arnaud, François-Marie Marchant de Beaumont and others, and infers from these sometimes sentimental publications that Père Lachaise and the other ‘new spaces of the dead’, as she calls them, were designed to be ‘edifying sources of moral and social reconstruction’, in which notions of egalitarianism central to the Republic were deliberately promoted. Visitors could reflect on these notions – in the form of semi-private, semi-public acts of communing – when they read the intimate but at the same time morally instructive epitaphs inscribed on tombstones.

In fact, the idea that, within the precincts of Père Lachaise, the dead were all equal was, of course, an illusion. Unlike the Catacombs, where ‘all distinctions of sex, wealth, and rank have finally disappeared’, as Etienne de Jouy justifiably observed in 1812, in Père Lachaise some of the dead were more equal than others. There were three options for those interring their loved ones, as Legacey explains. The poor could bury them for free in the area alongside the south-western wall of the cemetery, which had been designated ‘public’; the rich could purchase ‘perpetual concessions’, which guaranteed the deceased ‘a permanent place in the cemetery that could be embellished according to the owner’s means and desires’, at the not inconsiderable price of 100 francs per square metre; and a middling sort, consisting of people ‘who wanted something more private than the mass grave, but who could not afford the exclusive private plots’, consequently rented rather than bought what were known as ‘temporary concessions’, where the dead were limited, in the first instance, to a five- year tenancy.

The contemporaneous literature on Paris’ pioneering cemeteries, Legacey points out, tended to ignore this ‘stratified structure’, interpreting Père Lachaise in particular ‘as a profoundly unifying cohesive space’. Occasionally, however, the horrors both of mortality and inequality irrupted into this polite, politically optimistic consensus in ways that proved impossible to repress. In 1837, for example, as Legacey observes in a postscript to her compelling chapter on Père Lachaise, an official report noted that, some 30 years after its inception, the burial sites were becoming increasingly hazardous, in part because numerous mourners competed, rather desperately, to mark out individual portions of the mass grave. The mother of one child interred in a picturesque spot in the communal section of the cemetery, it transpired, had been maintaining what she assumed was her daughter’s grave, but which she discovered was nothing of the sort: ‘An exhumation revealed that the body beneath the garden was that of a young man, while the girl’s remains were actually located three coffins further down the trench.’

‘The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living’, Karl Marx wrote in The 18th Brumaire of Napoleon Bonaparte (1852). The living generations of Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary France, as Legacey demonstrates in this highly readable, thoughtfully argued reconstruction of the culture of burial and memorial in late 18th- and early 19th-century Paris, were determined that these dead generations, in literal as well as symbolic senses, might serve not to oppress them like a nightmare, but to contribute actively and substantively to their dream of a new regime that was oriented to the future as well as committed to coming to terms with the past.

Making Space for the Dead: Catacombs, Cemeteries, and the Reimagining of Paris, 1780-1830

Erin-Marie Legacey

Cornell

210pp £28.99

Matthew Beaumont is Professor in English Literature at University College London and the author of Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London, Chaucer to Dickens (Verso, 2015).