‘Gardens and Gardening in Early Modern England and Wales’ review

Gardens and Gardening in Early Modern England and Wales by Jill Francis explores four centuries of horticultural endeavours.

No garden survives intact from the Elizabethan or early Stuart period. Changing fashions and the essentially ephemeral nature of plants and flowers have left us with only remnants and glimpses and some much later (and rather questionable) recreations. Reliable information on gardens from this period is slight and garden historians (a relatively new discipline) have tended to focus on the well-known and relatively well-documented estates of royalty and the aristocracy.

No garden survives intact from the Elizabethan or early Stuart period. Changing fashions and the essentially ephemeral nature of plants and flowers have left us with only remnants and glimpses and some much later (and rather questionable) recreations. Reliable information on gardens from this period is slight and garden historians (a relatively new discipline) have tended to focus on the well-known and relatively well-documented estates of royalty and the aristocracy.

Roy Strong’s The Renaissance Garden in England set the tone in the late 1970s with research that focused exclusively on lavish royal and aristocratic gardens, such as Henry VIII’s Hampton Court and Lord Pembroke’s fantastical Renaissance gardens at Wilton House in Salisbury. Such research created an image of Tudor gardens as vast, sumptuous places full of pageant, complex patterning and theatre. Little emerged about the practicalities of plants and gardening.

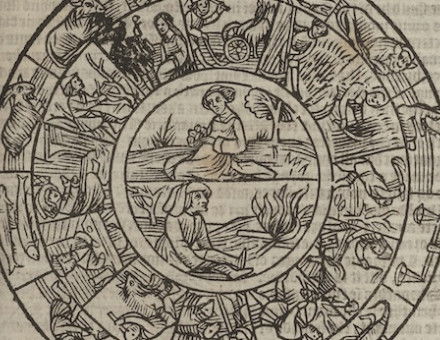

Pluckily heading to the other end of the social spectrum, Margaret Willes’ The Gardens of the British Working Class (2014) sought to explore 400 years of horticultural endeavours in the modest plots of the ‘lower orders’. For Tudor and early Stuart times, she made much use of the gardening manuals published from the mid-16th century: publications such as A Hundred Good Points of Husbandry (1557), with its jovial rhymes designed to help readers remember how and when to perform tasks, and The Country Housewife’s Garden (1618) gave instructions on everything, from digging and creating beds, to manuring, watering, planting and bee-keeping. Willes paints a picture not of lavish spectacle, but of the hard work involved in the production and storage of food from the garden.

Jill Francis has positioned her research somewhere between these two strands of society. She focuses on the gardens and, more importantly, the gardening activity of ‘the rural county gentry’, whom she categorises as knights, esquires and clergymen, people who owned their own land but were not part of the nobility. To this end, she has analysed an impressive array of 16th- and 17th-century manuscripts (household journals, correspondence, account books) to identify what was happening in gentlemen’s gardens at this time. She has interesting things to say about the role and skills of gardeners, the range of flowers being cultivated and the reasons why people gardened.

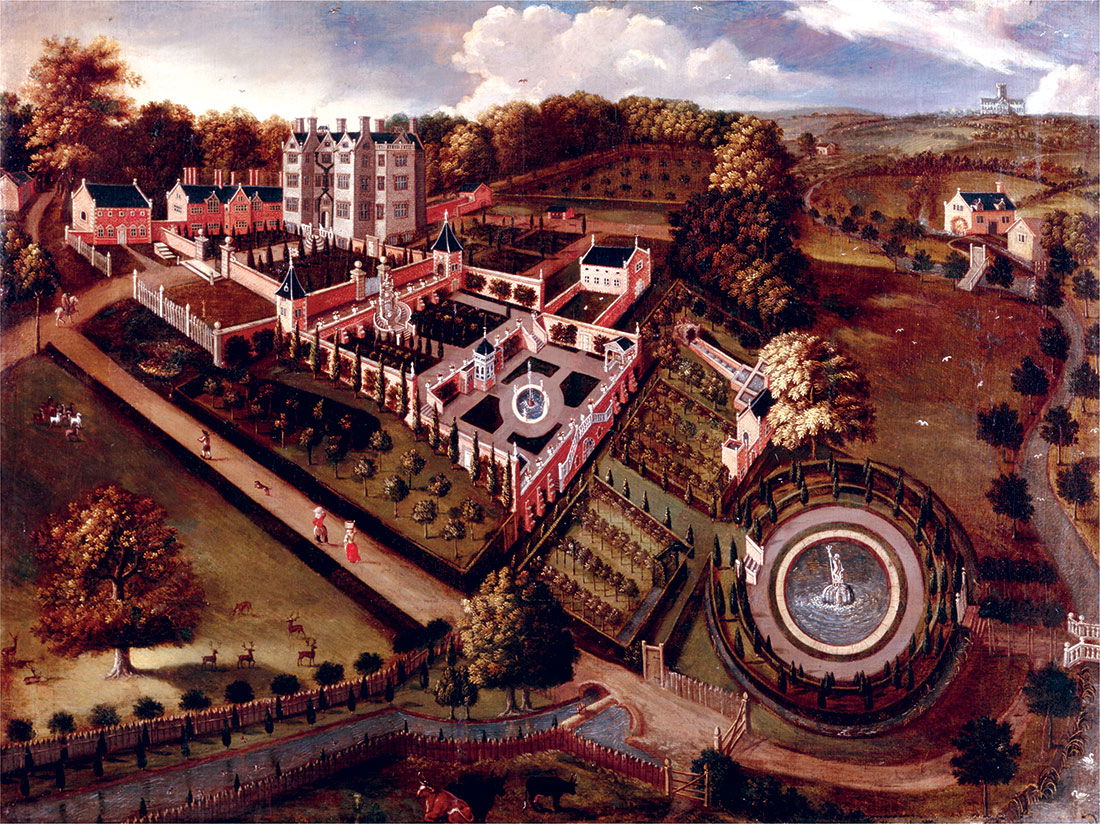

But it is a difficult focus to maintain. Despite her interest in practical gardening, much of her text simply describes various garden features and layouts and her sources range from images of grander gentleman’s gardens, such as at Trentham Hall in Staffordshire, with its vast Italianate terraces and fountains directly inspired by gardens of the nobility, to practical gardening journals (for which she supplies a helpful bibliography), which were probably pitched more at working gardeners and the lower orders studied in Willes’ book.

Francis is at her best analysing the previously unexplored archives of Sir Thomas Temple, including letters written to his estate steward about his garden at Burton Dassett in Warwickshire. From this we learn about how specific plants were chosen and propagated, where they were planted and how the soil was fed. It is a rare glimpse into the interests and activities of a possibly typical gentleman gardener in the early 1630s.

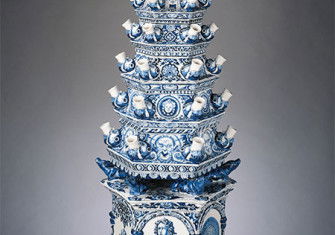

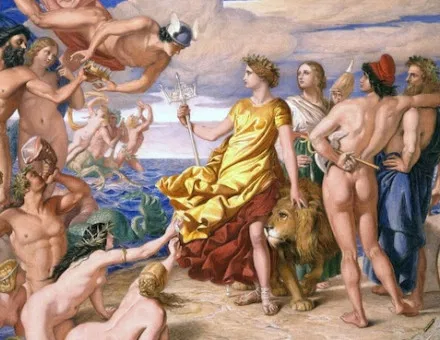

The book is splendidly illustrated with published and archival images from the 16th and 17th centuries, reproduced with great clarity and carefully analysed and explained. These are interspersed with colourful, but often less significant, contemporary photographs.

Despite its rather uninspiring title (the doctoral thesis on which it is based had the much jollier name ‘A ffitt place for any Gentleman’), this is an enjoyable study with much new material, new thinking and some excellently chosen and reproduced images.

- Gardens and Gardening in Early Modern England and Wales

Jill Francis

Yale 412pp £35

Jill Sinclair is co-editor of Historic Gardens Review and a tutor in landscape history at the University of Sheffield and the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education.