Feminist Energy vs Vehement Opposition

Four new studies challenge familiar tropes to consider some important but lesser-known areas of the women’s suffrage movement.

One hundred years after some women in Britain won the right to vote, we are once again experiencing an extraordinary moment of feminist energy and vehement opposition. A woman’s right to choose seems to be in reach in Ireland, yet is under increasing attack in the US. High profile campaigns on sexual harassment and equal pay are bringing together women across classes and countries, but legitimate concerns are being raised about whose voices are privileged within these movements. Women have new platforms and opportunities to share their experiences and tell their stories, but also face insidious harassment and violent threats when they dare to express an opinion, political or otherwise.

In this context, it is no surprise that people are looking back to the best-known battle for women’s rights for explanations and inspiration. Building on 40 years of feminist scholarship, a series of new books published this year goes a long way to challenge the conventional narrative and reveals how much more there is to know about the fight for the vote.

The most accessible of these histories is Jane Robinson’s hugely enjoyable Hearts and Minds. Robinson challenges public fascination with the suffragettes by demonstrating that their non-militant sisters were every bit as determined to succeed and equally as interesting. Her focus is on the little-known Great Pilgrimage of 1913, when thousands of women marched across the country for up to six weeks before joining together at Hyde Park in London. Their aim was to counter the argument – incredibly, still widely held – that the majority of women were uninterested in politics and did not actually want the vote. In the process, they faced hostility and violence with humour and dignity and Robinson argues that their courage and commitment should be understood as a vital strength of the campaign. She deftly manages a huge cast of characters and geographical scope in an immensely readable account, which is sure to reach and convince a wide audience.

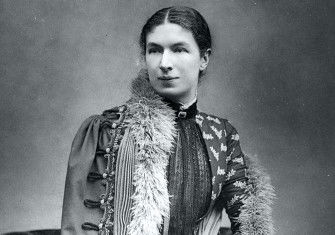

June Purvis’ Christabel Pankhurst revisits a familiar but still elusive and easily caricatured figure of the suffrage movement. Purvis and others have long argued that Sylvia Pankhurst’s highly critical portrait of her elder sister has come to dominate the historiography in an inaccurate and unhelpful way. If Christabel Pankhurst really was the autocratic monster that her sister claims, then why were so many women devoted to her? Purvis’ study seeks to re-establish Christabel Pankhurst as a credible political thinker, a resilient and effective leader and a human being as well as a figurehead. New sources, such as Pankhurst’s correspondence with the actress Elizabeth Robbins and the campaigner Jennie Baines, sometimes reveal exhaustion, uncertainty and touching concern for comrades, all very much at odds with Pankhurst’s strident public persona. Unlike many previous scholars who have seen Pankhurst’s turn to religion as a retreat from, or rejection of, feminist politics, Purvis thoughtfully considers the links between Pankhurst’s campaigns before the First World War and her postwar evangelicalism.

Christabel Pankhurst has been rather absent from the centenary celebrations this year, but Purvis’ study, which should become the standard account of Christabel’s life, very much justifies her place at the centre of the women’s movement.

We have long known that, for feminist campaigners, the personal is political: in their exceptional new collection of essays on suffrage and the arts, Zoë Thomas and Miranda Garrett show how frequently the professional was also political. The spectacle of women’s suffrage – especially in the forms of banners, processions and pageants – has been widely recognised and celebrated, but this insightful edited collection extends and enhances our understanding of the relationships between artistic endeavour, commercial enterprise and political activism. Few women, of course, could afford to be full-time activists: feminist artists needed to make a living and were often prevented from doing so by institutions, galleries and customers, who colluded in their exclusion.

This collection identifies how artists (men as well as women) created new products, positioned their output and companies within the feminist press and capitalised on new markets, as well as negotiating their own identities as ‘feminists’, ‘suffragists’ and ‘artists’, and debating artistic, political and business strategies.

Essays cover a full range of artistic output from fine arts and portraiture, to textiles and jewellery, badges and advertising. The collection hugely benefits from the inclusion of many vivid illustrations. The authors also take us from the familiar spaces of suffrage, such as Parliament and Westminster, to think about its significance in domestic interiors, workshops and studios. As such, this collection makes an invaluable contribution to understandings of visual and material culture and art and business history, as well as to suffrage and women’s studies.

Stage Rights!, Naomi Paxton’s excellent history of the Actresses’ Franchise League (AFL), highlights another group of women united by professional identity as well as a commitment to women’s suffrage. Enriched by Paxton’s own experiences as an actress and activist, which give her a performer’s understanding of theatrical space, the practicalities of staging and the business of theatre, she gives us an account of the AFL which places it as much within the history of political theatre as of women’s rights. She shows that, by adopting a position of neutrality on militancy, the AFL became a space of collaboration and co-operation between members of other suffrage organisations, challenging the supposed divide between ‘militants’ and ‘non-militants’. She also demonstrates how these women attempted to transform their own profession by establishing a women’s theatre to overcome the difficulties women faced as writers, managers and producers, as well as analysing their continued campaigns after the vote was won.

All these studies share a commitment to an inclusive vision of suffrage history that rejects well-worn stories and clichéd narratives in favour of expansive definitions and rich biographical detail. Each places the fight for the vote within a much longer struggle for women’s personal, professional and political rights. They show how a commitment to suffrage was central to women’s friendships, careers and lives and was expressed in a variety of surprising and creative ways. They make a fitting scholarly contribution to the centenary.

- Hearts and Minds: The Untold Story of the Great Pilgrimage and How Women Won the Vote

Jane Robinson

Doubleday 400pp £20

- Christabel Pankhurst: A Biography

June Purvis

Routledge 590pp £29.99

- Suffrage and the Arts: Visual Culture, Politics and Enterprise

Zoë Thomas and Miranda Garrett

Bloomsbury 272pp £85

- Stage Rights! The Actresses’ Franchise League, Activism and Politics 1908-58

Naomi Paxton

Manchester University Press 248pp £75

Lyndsey Jenkins is a historian and biographer at the University of Oxford and the author of Lady Constance Lytton: Aristocrat, Suffragette, and Martyr (Biteback, 2015).