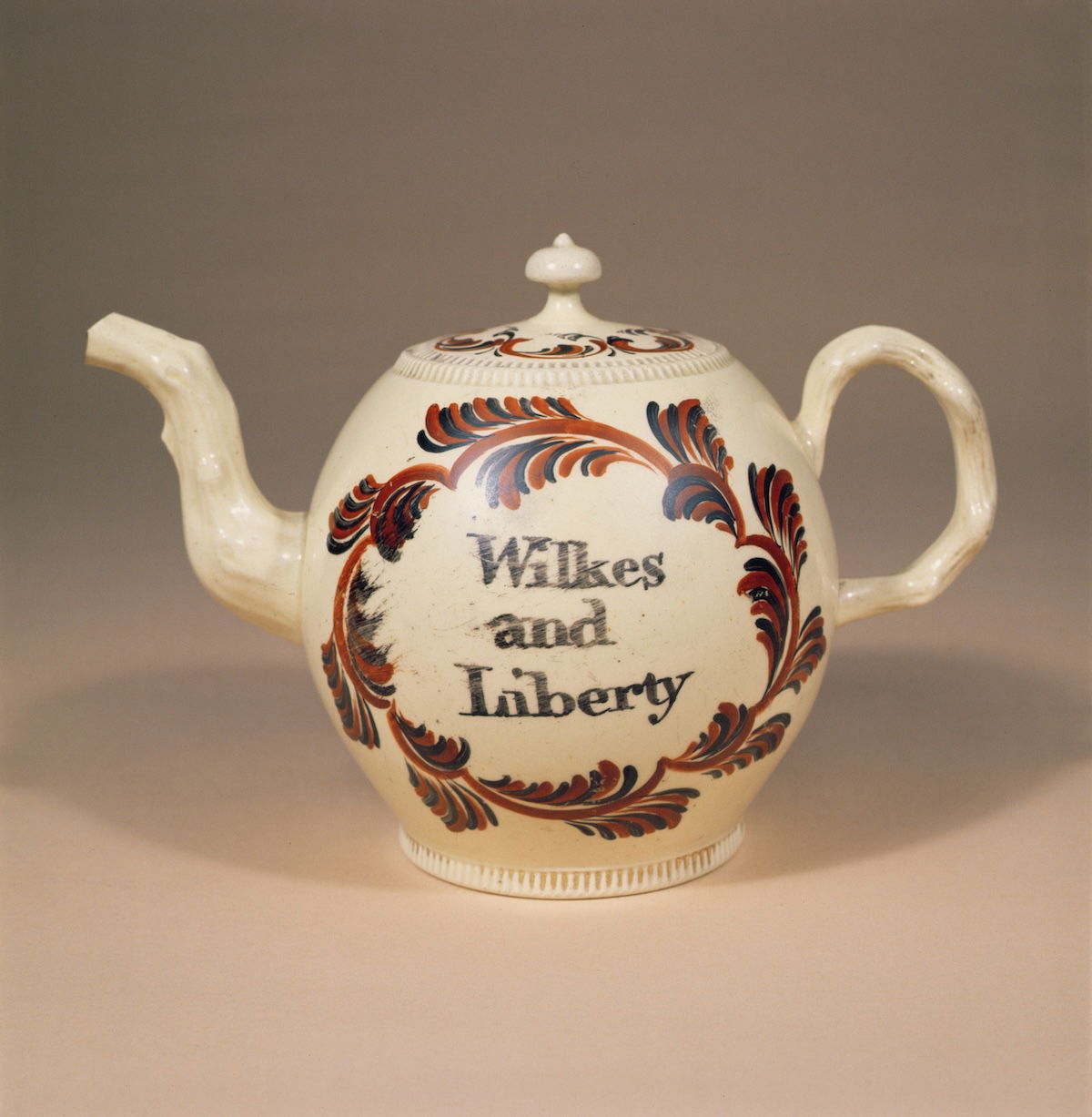

The Radical John Wilkes

Parliament’s champion of the people or scandalous, self-serving politician? Georgian radical John Wilkes kept a foot in both camps.

On 21 March 1776 the popular politician John Wilkes (1725-97) rose in a packed House of Commons to speak in favour of parliamentary reform. The franchise, he argued, was hopelessly out of date, with the state of representation in the country the same as it had been at the time of Charles II’s death in 1685. Too many seats remained in thinly populated counties, while growing cities had no representation. Wilkes advocated abolishing those seats and enfranchising overlooked towns, stating that too many ‘useful’ people of the artisan class were excluded from voting. He asked whether the current parliament could be said truly ‘to be the sense of the nation, as in the time of our forefathers’.