How Northern England Made the Southern United States

Tough, lawless and often violent, the outlook of the Anglo-Scottish borderlands profoundly shaped the culture of the southern United States.

Prospective homesteaders, in front of post office at United, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, 1935.

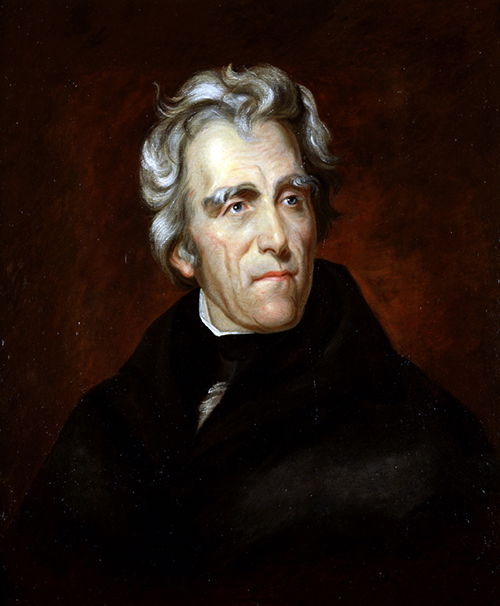

Andrew Jackson is still considered by many in the US to be the quintessential ‘Scotch-Irish’ president. Born in the backwoods of North Carolina to emigrants from County Antrim, his rowdy youth, instinctive belligerence and vengeful cruelty – as both a military commander and a politician – are seen as the very embodiment of the distinctively robust culture of the Appalachian highlands. But the American term ‘Scotch-Irish’ is misleading, for it obscures the Northern English origins of many of these settlers. Indeed, Old Hickory’s ancestors originated in the East Riding of Yorkshire, and were part of that first great migration from northern England and southern Scotland to the north of Ireland during the so-called Plantation of Ulster in the 17th century, before crossing the Atlantic a century later.

In his 1989 book Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America, the historian David Hackett Fischer explained how the regional patterns of emigration to the American colonies can help us understand the very different culture and political outlook of the peoples who live in the modern United States. While the Puritans from East Anglia established communities in New England, the Quakers went to Pennsylvania and what he calls the Anglican ‘Cavaliers’ made the valley of the Delaware their home. The ‘Mountain South’ was settled by a group he refers to as the ‘Borderers’ – a more accurate term than Scotch-Irish – with over 250,000 border English, Scots and Scots-Irish arriving in the Appalachian back-country between 1717 and 1775.

As with their deliberate removal in the 17th century from the Anglo-Scottish borders to the north of Ireland, the Borderers’ reputation for toughness meant that they were planted by the colonial gentry in the dangerous back country of Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas – ‘as a frontier in case of any disturbance’ – and from there into Georgia, Tennessee and Kentucky. For here was Indian territory, ‘debateable lands’ as recognisable as Liddesdale and Redesdale on the Anglo-Scottish border, with its wooded, hilly fastnesses, mobile ranching culture and regular confrontations with hostile neighbours. Sometimes these clashes would be with Native Americans, but more often they would be skirmishes with fellow ‘backsettlers’, as bloody as the clashes between the ‘Border Reiver’ families (marauding gangs of professional rustlers) that had made the land between Carlisle and Berwick-upon-Tweed such a perilous frontier.

The outlook of the Anglo-Scottish borderlands profoundly shaped the culture of the southern United States in a number of important and enduring ways. First, the seven centuries of warfare between English and Scottish kings meant that Northumbria in particular was much fought over – the ‘ring in which the champions met’ – and this made ordinary lives unusually precarious compared to the rest of England. Likewise, the lawlessness of these borderlands had created opportunities for theft and plunder on a massive scale, with the ‘Border Reivers’ building a whole way of life around the endemic theft of livestock. This created a very different and much more violent and militaristic society than in the rest of England. Societal structures were based around loyalty to local warlords, rather than the manorial system that prevailed elsewhere. Cumbrian and Northumbrian forms of tenancy were designed to maintain large bodies of fighting men to defend the border against the Scots, or to launch retaliatory raids against trespassers – the so-called ‘hot trod’ sanctioned by the ‘Marcher Law’ of the Borders. Here were the origins of the distinctive cowboy culture of the US, based as it was around the patrolling of grazing lands and the rapid pursuit of stolen goods via the armed posses familiar from American Westerns.

Border culture shaped patterns of association, too, with blood relationships becoming extremely important – especially when families grew into what the historian Ralph Robson has called ‘the English Highland clans’. Indeed, feuding was commonplace. If one man took a backward step in a confrontation, the entire clan’s honour was forfeit, or if one of their women was seduced and abandoned all of her menfolk would feel the humiliation keenly and usually seek bloody vengeance. The feud between the Hatfields and McCoys that raged for almost 30 years across Kentucky and Virginia was typical of the sort of vendettas that were so common among the clans of the Anglo-Scottish border.

These Borderers placed little trust in legal institutions, preferring instead to settle their disputes via the lex talionis of violence and blood money. It is telling that the term ‘blackmail’ (from the French mail, meaning rent), a system of paying protection money to powerful families, was invented by the Reivers. Even the tradition of building log cabins – which, again, was transplanted from the north British borderlands, where raids and home burnings were so common that investment in more substantial buildings was thought unwise – lives on in a certain inclination in the southern US towards impermanence, embodied in the predilection for prefabricated buildings and trailer parks.

In a country of hyphenated identities, a pride in Scottish ancestry – with the opportunities this provides for dressing up in tartan and tossing the caber at Highland Festivals – is inevitably more seductive than celebrations of English ancestry (a people notably bereft of a national costume). But the northern English origins of the southern US’s culture are deep rooted. They were first noticed by the Warwickshire-born folklorist Cecil Sharp, who spent months observing the culture of the Appalachian highlands. After a careful study of the traditional songs, ballads, dances and singing-games that he saw there he concluded that they had their origins in that part of England ‘where the civilization was least developed – probably the North of England, or the Border country between Scotland and England’.

The durability of that Border culture among these settlers was striking. First, American backcountry speech was descended directly from the language spoken by Northumbrians, Cumbrians and the Scots Borderers during the 17th and early 18th century. For example, the use of ‘man’ was – and is – commonly used in Cumberland and Northumberland by a wife to refer to her husband, as in the Tammy Wynette classic ‘Stand by Your Man’. Similarly ‘honey’ as a term of endearment was transplanted from north Britain (and lives on in Northumbrian speech as ‘hinny’), as well as ‘let on’ for tell, ‘nigh’ for near and ‘lowp’ for jump. The distinctive pronunciation of Appalachian and southern US speech too had its roots in north Britain: with ‘sartin’ for certain, ‘deef’ for deaf and ‘widder’ for widow.

The place names of this region also spoke of northern English roots. In North Carolina alone, there is a Durham Branch, several Durham Creeks, Durham County and Durham Township as well as the city of Durham (and the port most of these borderers landed in was Newcastle on the Delaware river). In Pennsylvania there are the counties of Westmoreland and Northumberland, as well as the dozens of places named after Cumberland – either the northern English county, or the ‘Butcher’ scourge of the Jacobites. There’s an Orange County in Virginia, too, and one explanation for the origin of the term ‘Hillbillies’ is that it derived from the backsettlers’ loyalty to William III.

The hardiness and aggression of the Borderers contributed to their cultural hegemony in this region by the time of the American War of Independence and they would go on to make names for themselves as formidable soldiers and politicians. At least 20 presidents have claimed ‘Scots Irish’ ancestry and Carlisle alone provided the ancestry of both Zachary Taylor and Woodrow Wilson. The baleful faces of these Borderers – look at daguerreotypes of John C. Calhoun, or the portrait of Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill – often bear striking resemblance to the contemporary descriptions of those North Britons who settled the Appalachian highlands. As Hackett Fischer described them, they were ‘tall, lean and sinewy, with hard, angry, weather-beaten features’. It is striking how much this physiognomy recalls the description in Linda Colley’s Britons: Forging the Nation of ‘Northumbrians and Lowland Scots [tending] to look alike, with the same raw, high-boned faces and the same thin angular physiques’ (for a good example consider Nathaniel Dance’s portrait of the Northumbrian gardener Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown).

But perhaps the most vivid vignette of the borderers’ enduring influence on America came via George MacDonald Fraser’s description – in his introduction to his study of the border Reivers The Steel Bonnets – of that moment in 1969 when the descendants of ‘three notable Anglo-Scottish Border tribes’ gathered for the US presidential inauguration in Washington DC, with Lyndon Johnson handing over to Richard Nixon in the presence of Billy Graham (while at Cape Canaveral, another descendent of the borderers, Neil Armstrong, prepared himself for the Apollo 11 Space Mission). Johnson with his ‘lined, leathery Northern head and rangy, rather loose-jointed frame’, and Nixon’s ‘blunt, heavy features, the dark complexion, the burly body, and the whole air of dour hardness’ which was, in MacDonald Fraser’s view, ‘as typical of the Anglo-Scottish frontier as the Roman Wall’.

Dan Jackson is the author of The Northumbrians: The North-East of England and Its People, A New History (Hurst, 2019).