The Creatures That Devoured Leningrad

The Siege of Leningrad imposed horrific conditions on its residents, severe food shortages among them. Remarkably, many of the animals in the city’s zoo survived.

Residents during the Siege of Leningrad, c.1941.

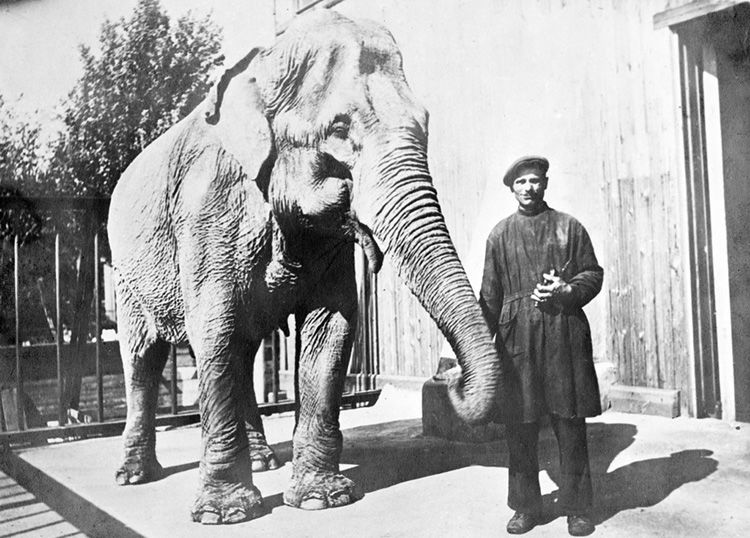

One of the first victims of the Siege of Leningrad was Betty. She had arrived in the city in 1911 and quickly established herself as an important part of her community. On 8 September 1941 – just a day before the siege began – German bombers attacked her home, causing it to collapse on top of her. Caught beneath rubble too heavy to move, she spent her final moments crying out in agony and terror. When she finally died, her body was dismembered and buried at the same place she had spent the better part of her 50-year-long life, one that had seen both the rise of the Soviet Union and its near demise at the hands of fascism. Betty was an Asian elephant and one of the many animals held at Leningrad Zoo that had to suffer through what is now considered the most destructive urban conflict in history.

The day of Betty’s death marked the grim start of what was already promising to be a long and difficult waiting game. Not only had the Nazis robbed Leningrad of one of its most cherished mascots, they had also demolished a warehouse complex near Zabalkansky Prospekt that contained much of the city’s supply of flour and sugar. Daily rations of bread, which had already been cut when the war with Germany began, grew slimmer still. By the end of autumn, adult workers were entitled to a mere 500 grams of bread a day, while their children and elders had to make do with fewer than 250. Lack of flour was often compensated for with sawdust and other inedible material and people tried to enrich their regimens with a variety of items, from petroleum and peat to household pets and, on rare occasions, even human flesh.

In light of such unfathomable desperation, the fact that not a single inhabitant of the zoo ended up on anyone’s menu is astonishing and is mostly thanks to the ingenuity of the caretakers. Around a third of the zoo’s rarest animals – including panthers, polar bears and a rhinoceros – were evacuated to Kazan before Leningrad was completely surrounded. The animals that weren’t moved then never left and maintaining their hefty, colourful diets during the ensuing shortages was difficult. The city soviet allotted them special rations of hay and vegetables, which smaller carnivores such as foxes and vultures could be tricked into eating as long as they were soaked in blood or bone broth. Larger carnivores, like tigers and eagles, were pickier, even as starvation loomed, and would only consume their meals when they were sewn into the skins of rabbits and guinea pigs.

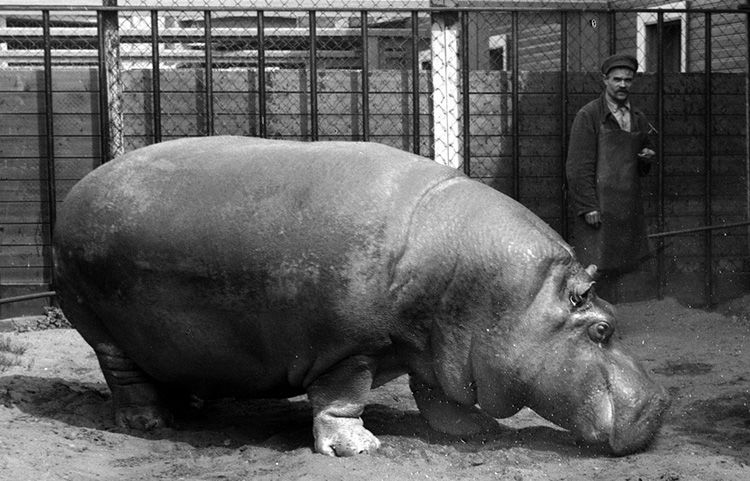

One of the most difficult creatures to take care of was a pygmy hippopotamus called Beauty, who had been brought to the zoo the same year as Betty, when she was a calf. Adult hippos require close to 90 pounds of sustenance a day and need constant access to water to prevent dehydration. Amazingly, the zoo’s caretakers not only managed to keep Beauty fed, but moisturised as well; when the pool inside her confinement ran dry during the winter of 1942, one devoted zookeeper reportedly took it upon herself to haul each day from the Neva enough water to give the hippo a thorough sponge bath. Unlike Betty, Beauty survived the siege, though she lost a considerable amount of weight. Veterinarians referred to the hippo as the pride and joy of the blokadniki and the historian Anna Reid described her prolonged life one of few ‘specks of light in a vast darkness’.

Though accounts differ, it is thought that the Leningrad authorities did not kill any of their animals throughout the siege, which makes them quite the anomaly among zoos in wartime. During the First World War, Antwerp Zoo killed its bears and big cats for fear they would escape in the wake of the German invasion. For similar reasons, London Zoo preemptively destroyed every poisonous snake, insect and spider in its possession. Most infamous of all was the Ueno Zoological Gardens of imperial Tokyo which, in the span of a single year, strangled its leopards, killed its bison and starved its elephants. While the Japanese government justified these disposals as precautionary measures against Allied bombings, some historians have since decried their motives as propagandistic demonstrations of sacrifice and martyrdom in the midst of a national emergency. In Cedar Rapids, Iowa, one ‘patriotic’ zookeeper slaughtered the majority of his own collection – which consisted of alligators, bears, bison, foxes and a wolf – because he deemed it unconscientious to supply them with such large quantities of food while the rest of the country was being put on rations.

In Reading Zoos (1998), Randy Malamud proposes that, during crises, zoos often become ‘an expendable luxury when played off against human duress’ and that, rather than depleting an already scarce food supply, animals may be butchered to add to it instead. This happened frequently, and often in conditions that weren’t nearly as dire as those endured at Leningrad. After the RAF bombed the Berlin Zoo, elephants and giraffes escaped their compounds only to be rounded up in the streets, killed and served in soup kitchens. Nor was the butchering of zoo animals exclusively done by the famished proletariat; when Prussian forces laid siege to Paris in 1870, the city’s elite plundered several exotic exhibits of the Jardin de Plantes and subsequently prepared them as part of their banquets.

How did so many of Leningrad’s animals, Beauty among them, survive? The Russian literary critic Lidiya Ginzburg, herself a survivor of the siege, argued that many Leningraders romanticised the war as a means of blotting out darker, more humiliating memories. A slightly more realistic hypothesis might attribute the animals’ survival to the political interest that may have been vested in them. Having spent decades working in Soviet archives, the Russian scholar Nikita Lomagin proposed that the zoo’s inhabitants might have been spared, among other reasons, to please the children of party officials stuck inside the city. Regardless, Leningrad Zoo became a symbol of pride for residents, proof that the city had not yet regressed into barbarism.

Tim Brinkhof writes on art and culture.