'Let My People Go!'

Hollywood offers a new version of the Exodus story, the West’s most enduring political narrative.

The release of Ridley Scott’s Hollywood blockbuster, Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), highlights the enduring appeal of the Old Testament’s most spectacular story. Yet few appreciate the extraordinary reception history of Exodus. From Constantine to Martin Luther King, it has been among the most potent narratives in the western political imagination.

The release of Ridley Scott’s Hollywood blockbuster, Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), highlights the enduring appeal of the Old Testament’s most spectacular story. Yet few appreciate the extraordinary reception history of Exodus. From Constantine to Martin Luther King, it has been among the most potent narratives in the western political imagination.

The early Christians adopted a ‘spiritual’ or ‘typological’ reading of Exodus. Humans were in Egyptian bondage to sin; Christ was a new Moses who redeemed his people from slavery; the Passover was a type of Calvary, where he shed his blood; the passage through the Red Sea symbolised deliverance from the Pharaoh Satan; the Wilderness was a picture of this life, with its wanderings and woes; death was crossing the Jordan; the Land of Canaan was an earthly foreshadowing of Heaven. This has remained the primary meaning of Exodus in Christian liturgy, hymnody and preaching.

In the fourth century, however, Christians started to read Exodus politically. The dramatic conversion of the Emperor Constantine rescued the early Church from the Diocletian persecution. Eusebius of Caesarea hailed Constantine as a new Moses. His victory at the Milvian Bridge in AD 312 was another crossing of the Red Sea. He was leading the new Israel to a Promised Land of milk and honey. For centuries to come, Christian rulers and their propagandists would enlist Exodus to burnish their image. Even Machiavelli would end The Prince (1513) by calling on the Medici to play the part of Moses and ‘liberate Italy from the barbarian yoke’.

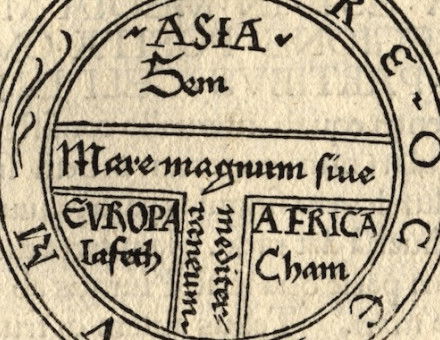

In the Protestant Reformation, with its relentless appeal to the Bible, there was a sharp intensification of Exodus politics. Martin Luther was presented as a latter-day Moses, delivering the Church from popish bondage. Calvinists developed a particularly close identification with the oppressed children of Israel and in the 1550s and 1560s they became embroiled in a series of uprisings in France, the Netherlands and Scotland. During the Dutch Revolt, William of Orange was portrayed as Moses and the Exodus story was used as patriotic scripture in sermons, songs, engravings, paintings and the stage. As Elizabeth I brought the Marian persecution to an end and John Knox led the Scottish Reformation, the title page of the ‘Geneva’ Bible of 1560 bore a striking image of the Israelites pinned against the Red Sea by Pharaoh’s horses and chariots, with Jehovah’s pillar of cloud in the distance. The Exodus was being used to forge a Protestant national identity. After the Spanish Armada was scattered by a terrible storm in 1588, the commemorative medal bore a text from the song of Moses and Miriam at the Red Sea: ‘Jehovah blew with his wind and they were scattered.’

In the English Revolution of the mid-17th century Exodus was mobilised on a grand scale by the parliamentarians. Oliver Cromwell told Parliament in 1654 that the deliverance of the Hebrews offered ‘the only parallel’ to England’s experience during the Civil Wars. England had been liberated from civil and ecclesiastical bondage and was making its painful progress through the Wilderness towards the Promised Land. The Royalist riposte to Puritan Exodus politics was displayed in a medal struck to celebrate the Restoration: Charles II appears as the young prince of Egypt returning to smite the Puritan taskmasters. When his brother, the Roman Catholic James II, was removed from the throne in 1688, there was a new wave of Exodus sermons, now praising William and Mary as Moses and Miriam.

In the American Revolution, Exodus was cited once again to justify political revolt. Tom Paine dubbed George III ‘the sullen tempered Pharaoh of Britain’. Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin suggested Moses at the Red Sea as a design for the Great Seal of the United States. This Exodus rhetoric backfired. American complaints about metaphorical enslavement by the British drew unwelcome attention to the all-too-literal enslavement of black bodies. Anti-slavery voices in both Britain and the US denounced the hypocrisy of white America. Black writers on both sides of the Atlantic now seized on the Exodus story, locating themselves within it as the new children of Israel. ‘For the first time in history’, writes the historian John Saillant, ‘slaves had a book on their side.’

In the decades to come, Exodus would be a key text for Anglo-American abolitionists and black preachers and activists, powerfully informing Protestant debates over slavery. The leaders of slave revolts hoped to re-enact the Exodus. Escape from the Southern states to the North was imagined as a flight from Egypt. Harriet Tubman, a ‘conductor’ on the Underground Railroad, was celebrated as a black Moses. Spirituals such as ‘Go Down Moses’ described America as ‘Egyptland’ and told old Pharaoh, ‘Let my people go!’. Ironically, Southern Confederates denounced Abraham Lincoln as a Pharaoh, but his Emancipation Proclamation was welcomed by blacks as a Mosaic deliverance.

Like the Israelites, however, African-Americans discovered that liberation could be a false dawn. Segregationist America could still seem like Egyptland, a Wilderness, a land of wanderings. Only in the marches and rallies of the Civil Rights Movement did black Americans acquire a new sense of momentum. On the night before his assassination, Martin Luther King electrified an audience gathered in a Memphis church by speaking as Moses to his people:

We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop … And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the promised land.

When Barack Obama ran for the presidency four decades later, he would tell black audiences that ‘the Joshua Generation’ was ready to complete what ‘the Moses Generation’ had begun. The heirs of Emancipation and the Civil Rights Movement were finally poised to possess the land of Canaan, or at least the White House. As in the days of Constantine, Exodus inspired visions of deliverance and empowerment.

John Coffey is Professor of Early Modern History at the University of Leicester and the author of Exodus and Liberation: Deliverance Politics from John Calvin to Martin Luther King Jr (Oxford University Press, 2014).