Henry III by David Carpenter review

A new account of some of the most exciting, terrible and important years in English history.

It is ironic that probably the best documented medieval English king is also one of the least well known. With the second volume of his biography of Henry III, David Carpenter continues his valiant attempt to address this imbalance. Carpenter expresses a concern that he remains an academic rather than a popular historian but, despite the length, there is nothing for the general reader to fear: this is history at its very best.

Carpenter is the perfect tour guide of the 13th century. The reader is carried along at a gentle pace, the prose scaffolded by a lifetime’s learning evident in the generous footnotes, and distilled into a conversational style. The reader is aided by two thematic chapters that explore the society of Henry’s England, and the intellectual and practical basis of the revolutionary regime of Simon de Montfort.

The task is made a little easier by the events the book covers. The 14 years (1258-72) described in this volume are some of the most exciting, terrible and important in English history. The book begins where the first volume left off, with the dramatic march on Westminster Hall by seven barons demanding the reform of the realm. Carpenter traces the often-twisted paths that reform took as the reformers argued among themselves, and Henry plotted to wrest back power for himself.

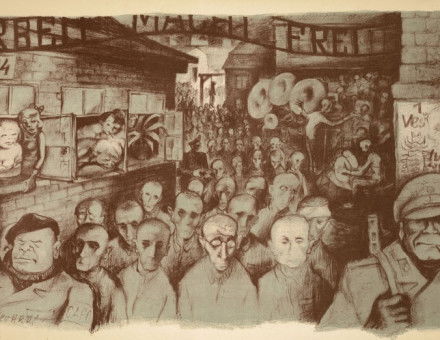

Far more radical than Magna Carta, which sought largely to regulate the exercise of royal power, the so-called Provisions of Oxford (the name given by reformers and historians to an array of reforms that took place in 1258 and 1259) wrenched virtually all executive power away from the king. The reformers corporatised royal authority among the barons, investing it in a council of 15 to rule with minimal input from the king. The work of the reformers exposed the failings of Henry’s personal rule and Carpenter takes us through the painstaking work of the justiciar Hugh Bigod as he travelled around the country, hearing the people’s complaints and trying to do genuine justice. The reformers sought to reach beyond the great lords to the lesser knights and gentry, to the church and even to the peasantry. The demands of the ‘community of the realm’ to preserve the Provisions and the oath taken at Oxford to uphold them were both inspiring and threatening. Those who dared to forsake their oath were to be regarded as mortal enemies while foreigners, especially England’s Jews, became, as so often, the scapegoat for the nation’s ills and the target of hostility and, increasingly, violence.

Reform slowly, inexorably, gave way to civil war from 1263 to 1267. The king, his heir and his brother were, after the catastrophic royalist defeat at Lewes in 1264, all prisoners of their triumphant enemy, Simon de Montfort. The Crown’s authority was laid low like never before and never again until the time of Oliver Cromwell. Nor had England ever witnessed such violece as that seen during the royalists’ revenge a year later at Evesham, a murder rather than a battle according to one chronicler. While the wounds of the civil war eventually healed, the poison of political violence remained in the bloodstream of the body politic.

The exact positions of individual actors as these bewildering events unfolded are confusing even for the expert, but Carpenter guides the reader safely through, explaining the heady mix of idealism, practical understanding and naked self-interest at play. Carpenter brings the huge supporting cast to life as real men and women struggling with real issues. We encounter the solidly royalist baron Philip Basset; the clever, young and hot-tempered Gilbert de Clare, whose principles led him both to support and then to oppose de Montfort and then to effect a final settlement in 1267; the ‘jeune men’ around de Montfort who died around their chief at Evesham, and the saintly Bishop Cantilupe who parted from de Montfort on the morning of Evesham shedding hot tears. There is also the wise and pious Louis IX of France whom Henry admired so much and who tried, and failed, to save Henry and England from themselves; the tricksy but courageous Lord Edward, Henry’s heir, who went through the hardest apprenticeship of any English monarch and emerged as a great and terrible king; the two Eleanors at the heart of Henry’s life, his sister, married to his greatest enemy, and his wife, braver and wiser than her husband yet also deeply implicated in many of the criticisms of Henry’s rule.

There is a danger, part way through the book, that Simon de Montfort will come to overshadow Henry. Carpenter’s de Montfort is both compelling and monstrous but, in the end, it is de Montfort who could not escape Henry’s shadow. Had Henry been his father, de Montfort might easily have deposed him, but Henry was not King John and Carpenter demonstrates how Henry’s fundamental decency was just as essential to saving him and his dynasty as Lord Edward’s martial qualities. Carpenter sums up Henry succinctly as ‘a king with a high sense of regality’s outward show, but sometimes a low sense of its actual practice’.

Westminster Abbey, which Carpenter rightly calls Henry’s ‘great achievement’, has taken centre stage, as Henry always intended, in this coronation year. Carpenter himself grew up in the shadow of the abbey (where his father was dean) and these two volumes stand as his legacy. Historians of the 13th century tend to view the era through the words of its greatest (and most voluminous) chronicler, Matthew Paris, whose Chronica Majora is both a blessing and a curse to those seeking to tell the story afresh. It has taken 40 years and a life in history, but historians of the future will have to approach Henry III through these twin volumes. In David Carpenter, Henry has finally found a wiser, better informed, more generous and fair-minded chronicler to do him and his reign justice.

Henry III, 1258-1272: Reform, Rebellion, Civil War, Settlement

David Carpenter

Yale University Press, 711pp, £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Andrew Spencer is Senior Tutor and Fellow in History at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge.