The Star is the Corpse

The dissection theatres of 17th-century Europe were tourist hot spots, spectacles that mixed medicine with art.

The anatomical theatre in the Archiginnasio of Bologna is one of the city’s most intriguing tourist attractions. For three euros, tourists can visit the anatomical theatre and the former university, one of Europe’s first. But the space is missing one vital feature: a corpse. In the 1650s the crowds would not have flocked to take photographs and gaze at the architectural features. Rather, they came to gawp at the dead.

The anatomical theatre in the Archiginnasio of Bologna is one of the city’s most intriguing tourist attractions. For three euros, tourists can visit the anatomical theatre and the former university, one of Europe’s first. But the space is missing one vital feature: a corpse. In the 1650s the crowds would not have flocked to take photographs and gaze at the architectural features. Rather, they came to gawp at the dead.

This cultural phenomenon was not just reserved for Italy, despite the presence of theatres in Padua, Verona, Venice and Rome. Across Europe, anatomical theatres affiliated with the early universities steadily became tourist attractions, due to the public dissections they held. From Leiden to Paris, Amsterdam and London, these unusual urban sites opened their doors to an enthused and interested public. As the 17th century progressed, the anatomical theatre became a focal point of city life, where the fashionable elite would gather. Not solely reserved for medical men, it represented an enlightened arena, where clergymen, magistrates, merchants, administrators and even royalty could mingle.

Bologna’s is not the only anatomical theatre that survives; Leiden and Padua serve as the earliest modern examples that continue to operate as tourist venues. Both built in 1594, they offered anatomy lessons in the form of weekly dissections for university students and the public alike. Sessions took place during the coldest months of the year – to preserve the corpses – with different ones dedicated to particular organs or systems of the human body.

In 1638 Bologna followed suit and, by the end of the 17th century, Europe was awash with anatomical theatres. Putatively designed for educational purposes, their function soon proved multifarious, as other uses quickly surfaced. Grandiose in scale, ornate in decoration, the varying theatres of Europe were often different stylistically, most had one thing in common: those dissected had been executed as criminals. Aside from Bologna, where relaxed laws allowed other methods of procuring the dead, most theatres relied on a flow of corpses coming directly from the gallows. In this sense, a trip to the anatomical theatre went hand in hand with viewing a public execution. Shortly after viewing a hanging or execution, witnesses could then see the same individual being dissected, and a strange, macabre and popular source of urban entertainment began to unfold.

As a result, viewing a public dissection came to mean more than just a medical investigation. In Italy especially, dissections took place during communal festivities; most notably, the Carnival. Despite the fact that these celebrations coincided with the cooler months, the historian Giovanni Ferrari argues that the intermingling of festivities and public dissections was a very deliberate choice by Bolognese officials, designed to encourage large audiences to attend. ‘Out of season’ dissections were often badly attended and labelled as unsuccessful by organisers, regardless of the usefulness of the lecture or the range of subjects covered. As one observer described, Bologna’s theatre was ‘one of the most renowned constructions in Italy, the constant amazement of foreigners, and the glory of the city wherein it was built’. This interplay between wonder, recognition and glory suggests that what was important here was not education or medical progress but, rather, a large audience, international prestige and a reinforcement of the university’s authority, medical or otherwise. As Jonathan Sawday notes, no respectable English traveller would travel to Holland and miss Leiden’s anatomical theatre, often the highlight of a visit. In 1641, the writer and diarist John Evelyn wrote that: ‘Amongst all the rarities of this place, I was much-pleased with the sight of the anatomy school, theatre and repository adjoining.’

By the mid-17th century the anatomical theatre was no longer seen, by the medical set at least, as a place of anatomical discovery. Rather, jostling crowds and competing academic factions meant that getting a good seat was tricky and students tended to rely on private closed sessions, reserved for medics, to advance their understanding of the body. Historians now argue that it was the ceremonial, symbolic and ultimately spectacular function of the anatomical theatre that drew in crowds. In Bologna, posters were papered up around the city announcing the date and time of the public sessions. Like a show or museum, entry was ticketed and, usually, paid for. Often, the audience would be entertained with music beforehand and reports were made of rowdy revellers and hecklers, excited by the festivities.

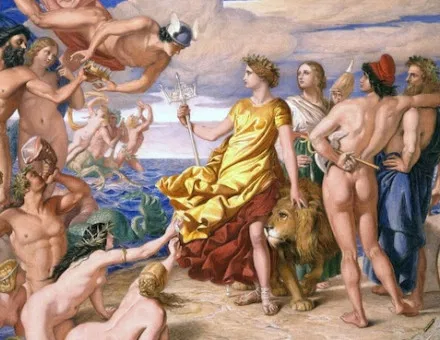

A vigorous set of rituals consolidated this sense of ceremony. The audience sat according to rank and a dress code was maintained. Theatres themselves were extremely beautiful and ornate, often loosely based on classical models, such as the Colosseum, and carved from wood. Like Roman emperors, anatomists behaved like showmen and often sat aloft on decorated ‘thrones’. The sense of spectacle was reinforced by wooden carvings of renowned physicians or eerie sculptures and wall paintings of skeletons, strange and unsettling mementos mori. All these elements created an enticing atmosphere of drama and display, where viewing the dead through an aesthetic and even celebratory eye was encouraged. Despite the disapproval of medical men, such as William Hunter, anatomical science had become a form of spectacle, its gaze no longer purely medical, which often descended into voyeurism.

Whatever the motive for viewing the dead, by the 1800s the popularity of the anatomical theatre was waning, as new teaching methods developed and public interest decreased. Today, some still stand, relics of a continuing relationship between medicine and the arts, a fascinating meeting point for historians of theatre, science and culture.

Anna Jamieson is a masters student of History of Art at Birkbeck, University of London.