Historians and the Freedom of Information Act

The British government should be more open in its dealings with researchers.

Documents are the lifeblood of historians. They provide the bricks to build our picture of the past. Nowhere is this more true than intelligence history, where those involved in events are either dead, left no account or are unable to talk about their work because of the Official Secrets Act.

Intelligence historians rely more than most on declassified files from the intelligence agencies, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), Cabinet Office and other government departments. The documentation may only reflect what officials knew or thought at the time – often wrong – but it gives the official mind and it is often the only information available.

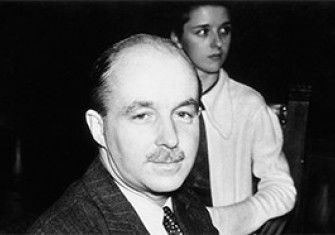

I have just finished researching a life of the Cambridge spy Guy Burgess, but information on his career is scant. Though there are dozens of files on his two years in the Far East Department, 1948-50, available with copies of his minutes responding to the Chinese Civil War and the British recognition of Red China, I found little else.

There was nothing on his time in the Information Research Department, a secret unit set up at the beginning of 1948 to counter Russian propaganda and which he betrayed months after it was set up, nor on his time in the News Department, in the private office of Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin’s deputy Hector McNeil nor the British Embassy in Washington. There is, however, one file censoring an article in 1977 by Denis Greenhill, a Permanent Under-Secretary at the FCO, about his former colleague Burgess.

The files are not available to the researcher even though they are over 60 years old and Burgess has been dead for over 50 years. By comparison all his BBC records are open and many available online. My discovery of a hitherto unknown spy linked to the Cambridge Spy Ring, Wilfrid Mann, came not from official documentation – all requests for disclosure were refused – but from the unpublished memoir of Sir Patrick Reilly, then FCO Under-Secretary in charge of intelligence, in Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

Making government records publicly available is an essential part of any democracy and we are supposed to have a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Under the Public Records Act it is also the law that all public records must be deposited in the National Archives after 20 years, unless a specific ‘instrument’ grants exemption. It is regularly ignored by government departments.

The declassification system should be simple. FOIA requests are made direct to the government department which has withheld the documents and the department must respond within 20 working days. If the department refuses to release material, researchers can then request an internal review and if that supports the initial decision – almost invariably the case because it is the government’s own department’s review – then the researcher can take the matter up with the Information Commissioner’s Office.

From my own experience this has not yielded results. FCO requests are processed by the Orwellian-sounding Knowledge Management Department. In the last nine months they have processed a dozen requests before deciding, without any discussion as required by law, to limit me to one FOIA request at a time. No new request has been processed since March.

The FCO has form here. A few years ago it was revealed that the FCO had some 600,000 files – some accounts say double that – going back to the mid-19th century held at their high security facility, Hanslope Park, which they share with MI5 and MI6. The files only came to light during a court case involving compensation for Mau Mau internees and only reluctantly did the FCO admit to their existence.

There is now a programme of releasing the documents but it is slow. Based on the time it has taken to declassify 20,000 colonial files, it is estimated it will take 75 years to clear up the Special Collections.

Certainly I have found Whitehall has many techniques to frustrate the Intelligence historian. For data protection purposes evidence is required that a person is dead. Website evidence, even from authoritative sources such as newspaper obituaries, is not allowed. Instead one is told to produce birth or death certificates, even for people born over 100 years ago.

Even though the espionage activities of Burgess and his merry men might be of public interest, this can be overridden by data protection. Until recently I could not look at Treasury files relating to Burgess’ payments in Moscow because the files also related to Donald Maclean, whose wife was still alive, although she had not seen her husband for almost 40 years. George Blake’s activities as a spy are protected under the Data Protection Act, even though he is an escaped convict who has written his memoirs and appeared in television documentaries.

This culture of cronyism needs to go. Either archives are secret or they should be made available to everyone. I discovered, for example, after being told it was not ‘physically possible’ to look at Burgess’ files, due to be released in October, that a BBC radio programme had been given unfettered access for several months at the beginning of the year. Tame journalists are often tipped off about document releases well in advance of the media in general and Records Days at the National Archives tend to be by invitation only.

There also needs to be more openness about exactly what is going on and better communication about release dates. We still do not know how many of the files from the Special Collections will be released within the next six years though some details of the FCO’s plans were outlined at the National Archives in November 2013 at a private meeting. Richard Drayton, a professor at King’s College, London, notes that ‘the FCO has so far released an inventory of such opacity that the public has only the slightest chance of identifying what is of “greatest interest”.’

The balance between accountability, transparency and open government and protecting national security is a difficult one to strike. Once records are released the genie is out of the bottle but it is hard to argue that records, which in many cases are over 60 years old and where the officials involved are dead, should not be released. If our history is to be written accurately, we will have to have all the records made available – not just those a government department believes we should have.

Andrew Lownie is the author of Stalin's Englishman: The Lives of Guy Burgess