Music of Resignation

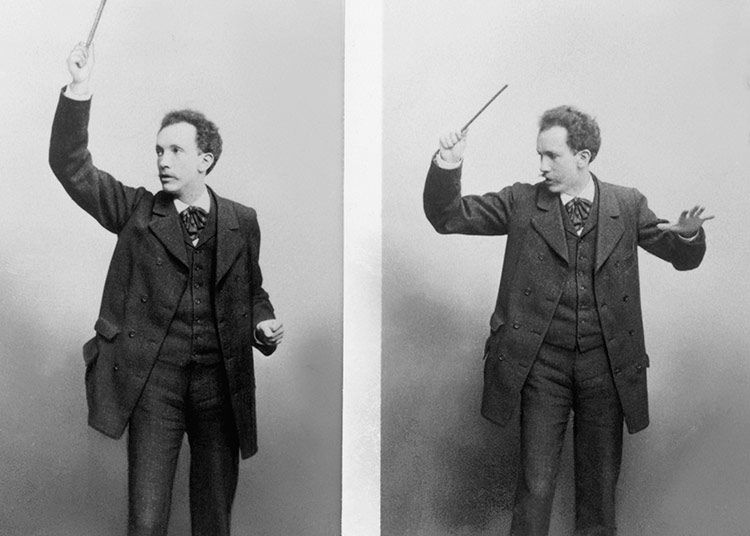

Richard Strauss trod carefully through a century of turbulence, trauma and transformation.

A tenor rehearsing Richard Strauss’s opera Salome once astonished me by saying ‘Glorious music, but what an old Nazi!’. Are such objections reasonable?

A tenor rehearsing Richard Strauss’s opera Salome once astonished me by saying ‘Glorious music, but what an old Nazi!’. Are such objections reasonable?

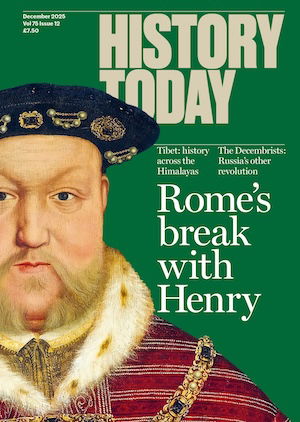

Born in Munich in 1864, his 150th anniversary was celebrated in the 2014 BBC Proms. From tone poems written in his twenties and early thirties to his 1945 Metamorphosen, they produced a bounty of orchestral and instrumental music. Tone poems, such as Don Juan and Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration) – both written in 1888-9 – were his first claim to fame but the major achievements are his operas. Salome (1905), set to his own abridgement of Oscar Wilde’s play, first propelled him to stardom, followed by Elektra (1909) and Der Rosenkavalier (1911), both collaborations with the poet Hugo von Hofmannstahl. By the outbreak of the First World War he was a wealthy man, wisely lodging part of his money in London, though it was sequestered when war broke out. If Strauss later exhibited a nervous attention to his income, who can blame him?

Unlike the impecunious Wagner, a revolutionary who relied on the largesse of others, Strauss achieved financial independence relatively early, yet like Wagner he was no milquetoast. His tone poems made him the ‘arch fiend of modernism and cacophony’ and Salome caused an international scandal. The Dresden premiere elicited 38 curtain calls, though British reticence led to a five-year delay and even then its production was initially banned. Finally Thomas Beecham got it into the Covent Garden programme a year after Elektra, but the Lord Chamberlain was having none of it and the story of how Beecham succeeded in circumventing this is fascinating.

He went to the prime minister Herbert Asquith’s country home, persuading him to intervene so that Britain could avoid looking foolish in the eyes of the world. The intervention was successful and in due course Beecham was called to the Lord Chamberlain’s office to strike a compromise. Nothing was cut, but the words were changed, bowdlerising the interactions between Salome and John the Baptist and banning the appearance of the latter’s severed head. Its replacement was a platter simply covered by a cloth. Salome’s line, ‘If you had looked at me you would have loved me’, was replaced by ‘… blessed me’.

Beecham managed to talk the singers round to the new words, but when the performance got underway their restlessness got the better of Finnish soprano Aino Akté and she made a slip, lapsing into the eloquent viciousness of the original. The infection spread and, before long, the cast was restoring the original words. Beecham tried but failed to drown out the singers, aware that Covent Garden was under the direct control of the Lord Chamberlain’s office. When the curtain came down he saw the Lord Chamberlain’s party coming towards him from the wings. Resisting an urge to flee, he decided to stand his ground and was astonished to find they had all come to congratulate him. As he wrote later, he never knew ‘whether we owed this happy finishing touch to the imperfect diction of the singers, an ignorance of the language … or their diplomatic decision to put the best possible face on a dénouement that was beyond either their or my power to foresee and control’.

Salome and Elektra were brilliantly realised at last year’s Proms, as was the Mozartian charm of his next opera, Der Rosenkavalier, fresh from its controversial new staging at Glyndebourne. Had Strauss died after these, they would have secured his reputation: when US troops knocked on his door at the end of the Second World War, he greeted them with the words: ‘I am Richard Strauss, the composer of Rosenkavalier.’ Yet Strauss achieved far more, including his next two operas, Ariadne auf Naxos and Die Frau ohne Schatten, great works both.

The second of these, premiered in 1919, marked the start of a five-year stint as co-director of the Vienna State Opera, after which, aged 60, Strauss produced the delightful Intermezzo to his own libretto. Meanwhile, the collaboration with Hofmannsthal led to a new opera on the Greek myth about Helen spending the Trojan War in Egypt, but it failed and Strauss requested another Rosenkavalier. The result was Arabella, but Hofmannsthal died of a stroke during its composition and by the time it came to stage in 1933, Hitler had come to power.

This was a disaster for Strauss. His new collaborator, the Austrian author Stefan Zweig, was Jewish and Strauss only got Zweig’s name on the playbill for the new opera in 1935 by threatening to withdraw the whole thing. The Nazis, who had proclaimed him president of the new Reichsmusikkammer without consultation, eventually gave way but the opera was allowed only three performances and Strauss was instructed to resign his position.

The loss of Hofmannsthal and Zweig was a great blow. He never again found a creative literary genius to work with and never recovered his operatic cutting edge. Yet fine works were still to come and in the late 1930s a Hofmannstahl scenario from 1920 was dusted off and amended for Strauss’s last three-act opera, Die Liebe der Danae, about Danae’s love for a human and rejection of Jupiter. Its premiere was originally intended to honour the composer’s 80th birthday in 1944 but, following the assassination attempt on Hitler, all theatres were closed and only a single dress rehearsal was allowed. It is now rarely staged, but in a concert performance this year in Frankfurt, the Act III orchestral interlude known as ‘Jupiter’s Resignation’ proved riveting. These final works – the posthumous Four Last Songs among them – give a representation of resignation and death arguably unmatched in music, but death was something Strauss understood early in his career and, as he said as he lay dying in 1949, it felt just as he had written it in Tod und Verklärung.

As for Nazi sympathies, those who know the facts have at worst accused him of looking the other way; nearly 70 when Hitler came to power and, with a Jewish daughter-in-law and granddaughter whom he protected throughout, he had to tread carefully. As for age weakening his muse, the undeniably great Four Last Songs were written when he was 85. After the war, opera moved on, with composers such as Benjamin Britten, and though Strauss belongs to an earlier genre, he remains in his way utterly incomparable.

Mark Ronan is Honorary Professor of Mathematics at University College London.