Puncturing the Powerful

During recent turmoil, Greeks have called on their history to form their political protests and criticise the powers they feel are oppressing them.

Greece has dominated the headlines of late. The world's press has become enamoured with the international contest as a nation in turmoil attempts to take on the huge European machine. Events we see unfurling today are the result of years of struggle between Greece and her European creditors, having defaulted on massive debts she accrued in an effort to heal her catastrophic economy. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras' promises to reverse previous governments' conservative policies and bring an end to savage austerity carried him and his socialist Syriza party to power in January 2015.

Greece has dominated the headlines of late. The world's press has become enamoured with the international contest as a nation in turmoil attempts to take on the huge European machine. Events we see unfurling today are the result of years of struggle between Greece and her European creditors, having defaulted on massive debts she accrued in an effort to heal her catastrophic economy. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras' promises to reverse previous governments' conservative policies and bring an end to savage austerity carried him and his socialist Syriza party to power in January 2015.

Tsipras and his finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, spent months in a bitter stand-off with Troika (the Greek term encompassing the IMF, European Commission and European Central Bank). A referendum on July 5th returned great support for their hard line with their creditors. Despite this, eight days later, Tsipras agreed to a set of austerity measures of the kind he had so passionately opposed. Tsipras's compromise has sparked a fresh bout of civil unrest among Greeks, a sorry feature of the last five or six years. Even the Units for the Reinstatement of Order (MAT), comprised of many right-wing Golden Dawn voters, have been deployed by Syriza to curb the incensed left-wing youth on the streets of Athens. The man who raised the hopes of ordinary Greeks has seemingly succumbed to the pragmatism of power. Political and economic structures have once more provoked chaos in Greek society. Greek protestors have turned to history to find solidarity and connect with past eras of strife, and to attack those at the top whom they blame for their plight.

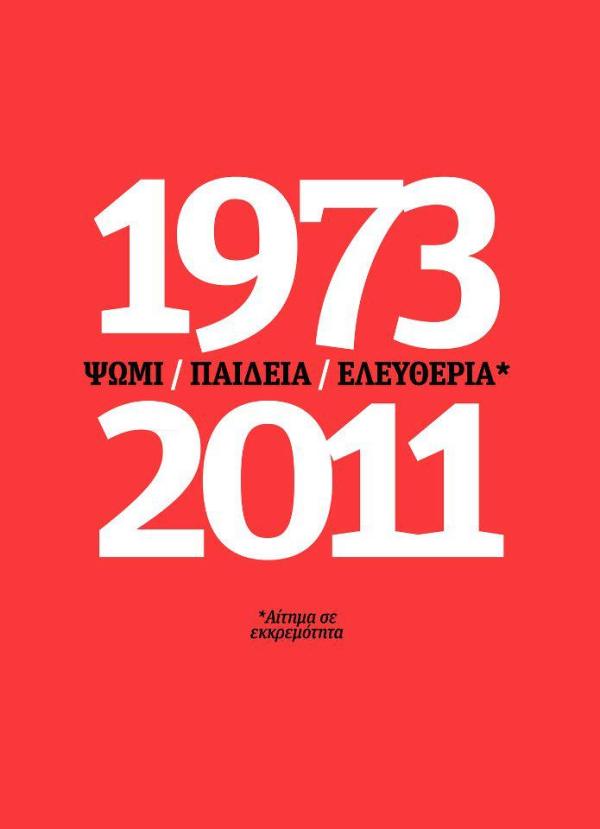

One of the popular ways history is invoked during protest is through powerful slogans. In 1973, following six years of oppression at the hands of the ruling military junta, students at Athens Polytechnic University gathered on campus to denounce the autocratic regime and demand a return to democracy. The students unified under the slogan: 'Bread, education, freedom', the three basic rights of citizens in any civilised, democratic society.

This slogan has been reinvigorated during the anti-austerity protests since 2009, gaining currency under economic deprivation and hardship. Once more Greeks consider their three privileges to be under attack from above as Troika imposes harsh austerity measures which their politicians are unable or unwilling to resist. 'Bread, education, freedom' is also used to commemorate the struggle of those Athens students decades earlier. In 2013 on the 40th anniversary of the student demonstration, Parliament House in Athens was beset with thousands of demonstrators, angry at their nation's demise. At the head of the huge protest, across the grand building, was the familiar slogan, along with the words: 'Junta has not finished in 73'.

This connection has been effected in other ways. During the teachers' anti-austerity strike in Athens in May 2013 a model tank was exhibited on top of a car among protestors chanting: 'Bread, education and freedom the junta did not end in 1973'. The 1973 protest ended tragically when a tank charged the university, killing 25 students. The use of the tank in 2013 highlights the notion that, decades after the restoration of democracy, Greeks feel they have returned to the dictatorial rule of Troika and Greek politicians.

Sometimes the historic connotations behind slogans are much less overt. In Greek popular culture, the cucumber is recognised as a crude metaphor for hardship: the pain endured as a result of being sodomised. Daniel Knight, an anthropologist at Durham University, has conducted interesting research into this very phenomenon and how cucumbers have prevailed in Greek urban street art and graffiti slogans from 2009. A photo taken by Knight displays the words, 'For five days you eat the cucumber, but on Saturday you are someone,' painted onto the side of a Trikala beauty salon. Knight also reported the response of a local woman in December 2013 on what the cucumber represents to Greek people:

The crisis is history repeating itself. We have a few years when everything goes well, life is good, and then the next crisis. The next cucumber if you like … The cucumber is the crisis, it is the depression and anxiety we have suffered in the past at different moments and we are expecting now. You have to 'eat' it, what else can you do?

The cucumber presents this crisis as simply the latest in a series of hardships in Greece's tumultuous history. Its obvious phallic aspect also suggests that Troika is sodomising the vulnerable Greeks.

Perhaps the most conspicuous invocation of history during Greek protests has been the use of the past to undermine power paradigms, between both the Greeks and Germans and between the Greek people and their politicians. Between 1941-4 Nazi forces occupied much of mainland Greece and millions suffered in extremely harsh conditions. The economy collapsed and urban centres experienced terrible famine. Estimates of deaths in Athens alone vary between tens of thousands up to 100,000. An equal trauma of the Nazi occupation was the brutal reprisals. Whole villages were razed to the ground and civilians were gathered up and executed – often including women and children. In, for example, the tragic massacre at Komeno in western Greece, 317 villagers were murdered during a Wehrmacht raid in August 1943. Victims ranged from one year old to 75 years.

As the major economy in the European Union, Germany is seen by suffering Greeks as the master of their nation's fate. Many see Angela Merkel as the puppet master of the EU, exploiting and protecting Germany's powerful position. She is regarded as the driving force behind the harsh austerity measures subjected on Greece from 2009-15, and which Tsipras has recently agreed to implement. Ordinary Greeks feel they are victims of another German occupation.

Protests and demonstrations have provided demoralised Greeks with a platform to undermine what they perceive as Germany's imperious attitude, primarily by referencing Germany's dark history. One such campaign, in which 50,000 Greeks turned out to exhibit their anger, greeted Merkel on her visit to Athens in October 2012. Fascist salutes, Nazi uniforms, swastikas and Greek protestors chanting anti-Nazi slogans greeted her entourage. Among the more conspicuous imagery there were also challenges to the pervasive sense of Germany's economic aloofness. In one example, a woman brandished a 'wanted' poster featuring Merkel's face with a toothbrush moustache and the word 'Siemens' around her neck, marking out the German manufacturing company who were involved in the exploitation of slave labour in concentration camps such as Ravensbruck and Darlau, where many Greek prisoners of war perished in the 1940s.

Memories of the occupation period have also been used by Greeks to implicate and accuse contemporary Greek politicians of treachery. Under the Axis occupation, a series of collaborationist quislings cooperated with Nazi authorities, considered a terrible betrayal by their compatriots. Ioannis Rallis was the third and final quisling prime minister who, in 1943, inaugurated the Security Battalions to combat left-wing Greek resistance forces, surrendering any claim to protecting the nation's interests. This move set Greeks against Greeks and contributed to the decades of fratricidal enmity in the country following the war. Indeed, many members of Golden Dawn today are descendants of members of the Security Battalions, sharing their disdain for the left.

These memories have led to similar conceptions of the political dynamics now as existed during the occupation. Politicians in Greece have been strongly accused of betraying the Greek public and of wilting before pressure from European leaders to implement crushing austerity measures. During anti-austerity protests Greek politicians as much as anybody have been the source of vitriol. Parallels have been drawn between the role of the quislings and that of contemporary politicians who appear to have thrown their lot in with the European plutocrats. Indeed, since reneging on his clear promises to the Greek people, Tsipras has been denounced by some leftists as little more than a Nazi, with similarities identified between his use of the MAT and Rallis's deployment of Security Battalions in 1943.

In times of struggle, people look to history for different reasons. History offers a common reference point against which people can view their present. In Greece, history has been an extremely prominent feature of the many demonstrations arising from the economic turmoil since 2009. It has been used to find solidarity with past struggles from below, such as that of the Athens Polytechnic students in 1973, and simultaneously to draw comparisons between a recognised past of stifling oppression and present conditions. History has also been a source of strength, as evidenced by the role of the cucumber in Greek popular culture. Understanding hardship as part of a historic cycle, which includes overcoming adversity and prevailing, provides a sense of rationale. Finally, history has been wielded by Greeks as a stick with which to beat their adversaries, be they Greek politicians or German creditors. Dark and shameful histories have been invoked to counter the humiliation to which Greeks feel subjected, and to challenge the prevalent power paradigms which render Greeks seemingly powerless.

James England is a recent history graduate with a keen interest in Greece's tumultuous recent past.