Putting a girdle ‘round the globe

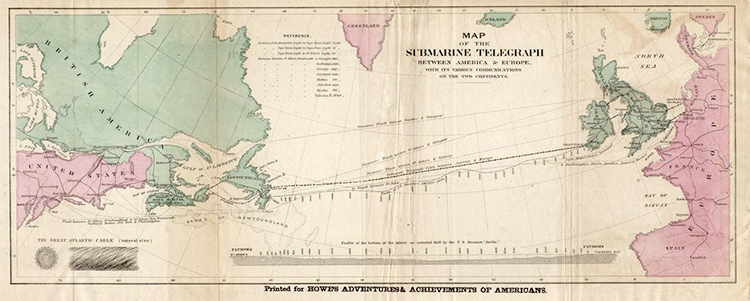

The transatlantic cables built in the mid-19th century shrank time and space.

It stretched 1,900 miles, from Valentia Island in western Ireland to Heart’s Content in eastern Newfoundland: the transatlantic cable of 1866. An earlier attempt had been made in 1858 and Queen Victoria managed to send a congratulatory telegram to US President James Buchanan – but after two months that earlier cable had already failed. It took another six years of heroic effort to realise transatlantic telegraphy for good. Global communication and commerce entered a new era.

It stretched 1,900 miles, from Valentia Island in western Ireland to Heart’s Content in eastern Newfoundland: the transatlantic cable of 1866. An earlier attempt had been made in 1858 and Queen Victoria managed to send a congratulatory telegram to US President James Buchanan – but after two months that earlier cable had already failed. It took another six years of heroic effort to realise transatlantic telegraphy for good. Global communication and commerce entered a new era.

The 150th anniversary of laying the 1866 cable is now celebrated by a fascinating exhibit at the Guildhall Art Gallery in collaboration with King’s College London and the City of London. The star of the show is the cable samples themselves, barely thicker than a thumb, and produced by Siemens Atlantic. These cables show how global communication was in itself only made possible by global trade and the imperial exploitation of resources. Inside the cable, copper was coated in gutta-percha, a natural rubber from Borneo. The strands were then twisted to make a core and wrapped in jute, before they were sealed with more gutta-percha. The transatlantic cable needed 300 tons of this natural rubber which led to the destruction of 26 million trees a year in Borneo. On top, the cable used 340,000 miles of wire.

The exhibit includes fine paintings of the Great Eastern, the largest steel ship built at the time, which carried the 7,000 tons of cables, coiled in tanks. Viewers can admire the copper pot battery of Daniel Cells as well as several code books and cryptographs used to decode messages.

Sending messages was not as cheap or straightforward as today in the age of text-messaging and mobile phones. Such was the length of the cables and the problem of electrical resistance, that, on a good day, it took a minute to send a dozen words. At $5 a word, it was hardly a snatch. Nonetheless, it was a giant leap for globalisation. Everything from the price of cotton to battle news could now be transmitted at unprecedented speed across the Atlantic.

While the material components are enough to make the visit worthwhile, the paintings that surround them require more of a leap of imagination from viewers. The exhibit tries hard to play with the cultural attributes of communication and place these processes in society at large. 'Transmission' and 'resistance' are core themes. We are thus invited to look at two polar bears sinking their teeth into shipwrecked sailors, in a Landseer painting of 1864, to ponder the force of 'resistance' – a somewhat different fate from what slowed down signals as they travelled along the wire. Transmission is paired with a painting of a girl, struck by plague, who is separated to stop the disease from spreading. Pictures of London, the navy and Egypt remind us of the global power of the British empire at this time, although there is surprisingly little about the United States and Canada in what was after all a transatlantic enterprise; the initial brain behind the whole scheme had been a Canadian, Frederic Gisborne.

The transatlantic cables shrank time and space. The acceleration of life is unimaginable without it, although we only glean fragments of their impact on culture and society in this exhibit. Jules Verne observed them in his Nautilus Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

Today, globalisation is once again under threat. It may even be unravelling. Victorians Decoded: Art and Telegraphy is a timely reminder of an earlier age of globalisation and of all the mind, muscle and material needed for us to communicate across the world.

Victorians Decoded is at Guildhall Art Gallery in the City of London from 20 September 2016 until 22 January 2017.

Frank Trentmann is the author of Empire of Things (Penguin).