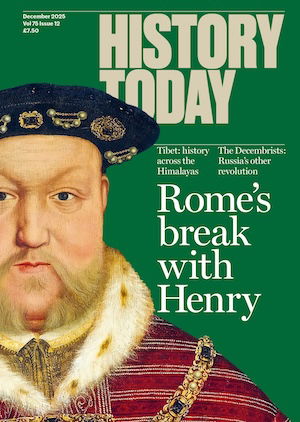

Should One Nation Mean One Language?

David Cameron’s desire for immigrants to learn English is part of a debate dating back to the origins of the modern state.

France, 1794. With the Reign of Terror in full swing, France at war with every other major European power and civil war raging in the western provinces, the deputies of the National Convention took time to consider a matter of crucial importance: the language of their fellow citizens. At the time, the majority of the population spoke little or no French, communicating instead through regional languages and dialects. The leaders of the revolution feared that without linguistic unity the fledgling Republic would be swept aside by a wave of counter-revolution and foreign invasion.

The fears of the revolutionaries offer telling parallels with contemporary debates in the UK about the links between language and citizenship. Critics of mass immigration warn of dangerous, ghettoised minorities that threaten the cohesion and security of wider society. Migrants, they insist, must integrate themselves, above all by learning English. This is a favoured theme of British Prime Minister David Cameron, as seen in recent comments on the language of immigrants, especially Muslim women. The government plans to increase funding for schools teaching English to immigrants, but also requires that those entering the country to live with their spouse learn English under threat of losing the right to remain in the UK.

The premier’s desire to build an ‘integrated and cohesive One Nation country’ resonates with the views expressed over 200 years ago in a very different context by Bertrand Barère, a member of the French National Convention and the ruling Committee of Public Safety in 1794, for whom linguistic diversity was a grave threat. By linking an ignorance of English to backwardness, patriarchal oppression of women and the threat of violent extremism, Cameron echoes Barère, who claimed that ‘to leave citizens in ignorance of the national language is to betray the fatherland, it is to leave the stream of enlightenment poisoned or blocked in its path’.

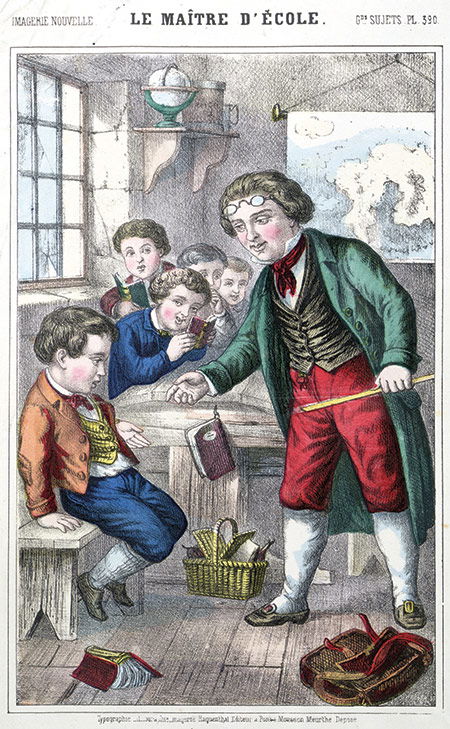

Concerns about the linguistic unity of nations have a long and often murky past. Just like Cameron, the revolutionaries sought to impose the use of their national language on those who did not speak it. As the abbé Henri Grégoire, Barère’s colleague in the National Convention, remarked, the aim was to ‘annihilate’ other languages and ‘universalise’ French. Schools were the favoured means of achieving this and primary school teachers were obliged to instruct their students in the national language. During the 19th century a variety of unpleasant measures were developed in French classrooms to ensure the language took hold, most notably the use of the infamous ‘symbol’, the French counterpart to the ‘Welsh Not’. This involved the use of a ticket, ribbon or other token, which would be given to the first child to speak in their native tongue. The student would keep this object, sometimes grasping it arm extended, until another child used the language and the token could be passed on, with a punishment distributed to whoever was left holding it at the end of the day. This practice was intended not only to make sure children practised their French, but to impart a sense of shame in speaking one’s native tongue.

Throughout 19th-century Europe, nationalists pursued linguistic unity with similar vigour and this has often manifested itself in state-sponsored discrimination. Linguistic minorities, especially Polish speakers, in the second German Reich suffered under Bismarck’s Kulturkampf during the final decades of the 19th century, an experience similar to those enduring Russification under Tsars Alexander II and Alexander III at roughly the same time. As in France, this involved the imposition of the national language in schools and also the restriction of civic rights and freedoms for linguistic minorities.

This is not just about tolerance or intolerance of minorities; it also touches on questions of individual freedom and citizenship raised during the French Revolution. Cameron insists that teaching English to immigrants is also about individual freedom, that without knowledge of the common language, individuals are denied access to the choices enjoyed by the majority. The abbé Grégoire’s opposition to linguistic diversity in France had similar roots. Grégoire feared that the interests and rights of ordinary people would never be recognised unless they could read and write enough French to participate in politics. As Grégoire argued in his speech before the Convention in 1794, the collective rights of minorities to have their culture respected conflicted with the rights of individuals to participate fully in society. These individual rights could be secured only through the intervention of the state.

The UK today is not Revolutionary France, nor is it Tsarist Russia or Germany under Bismarck, but these historical experiences can illuminate our current debate about the relationship between language and citizenship. Most pertinently, it is worth observing that language policies have often not worked quite as politicians hoped. France only achieved a real degree of linguistic unification after the Second World War, revealing the limited ability of the state to impose its will in matters of language. Efforts under Napoleon to create a monolingual legal system were opposed by legal officials who continued to communicate with locals in regional languages in order to be understood. Grégoire, like many contemporaries, hoped that large-scale conscription to the French-speaking army would assimilate the rural population, but when veterans returned home they often returned to the local dialect under pressure from families and friends. Even the French school system, universal and free at primary level after 1881, was less important than urbanisation and the development of transport links in the countryside. Discriminatory policies in Russia and Germany were often counter-productive, strengthening the appeal of minority identities and stimulating opposition. The history of language and the state in Europe shows how the social and economic context influenced the linguistic choices of individuals far more than narrow government interventions.

Stewart McCain is Lecturer in History at St Mary’s University, Twickenham.